ORGANIZATION OF THE SCHEME

[National Archives of Ireland CSORP 1849/O68O8 Emigration of Female Orphans. Letter from the Colonial Land and Emigration Commissioners(CLEC) 9 December 1848 answering the Lords Justices’ complaint about the delay in sending orphans. There must be a new classification in the Archives nowadays? CSORP 1849/O68O8 contains both a manuscript and a printed copy of the CLEC Report used below. You should be able to access it online at http://www.dippam.ac.uk/eppi/ You may have to type that address into your browser. Look under LC Subjects page 30 and ‘Emigration and Immigration’ about six items down the list.]

The paper trail of the Earl Grey scheme is quite easy to follow in official documents, albeit written from the perspective of government bureaucrats. I’m always amazed by the amount of time and energy taken up with parliamentary enquiries and commissions; it is a Public Service being created I suppose. At least the screeds of paper allow us to follow the female orphan emigration scheme being organized and refined. And they alert us to the efforts being made to ‘protect’ the young women.

The paper trail basically runs from Earl Grey to the CLEC (see above) to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in Dublin Castle, back again to Whitehall and forward to the Irish Poor Law Commission, thence to Boards of Guardians in various Irish Poor Law Unions. Once eligible candidates were found in the workhouse, the Commissioners arranged for an officer, Lieutenant Henry, to examine them and when approved, the Guardians made arrangements to provide clothes and boxes and arrange the orphans’ passage to Plymouth. The Commissioners were responsible for arranging the voyage to Australia. This post would become even more complicated if I was to explore fully the correspondence between different government departments in Whitehall; for example, between Earl Grey and Lord Grey in the Home Department and between Lord Grey and George Trevelyan in the Treasury. I’ll leave that to some stouthearted researcher in the future and for the moment, try to keep things as simple and as clear as possible.

In February 1848 the CLEC reported favourably on the proposal that “an eligible class of Irish emigrants might … be obtained from among the orphans now maintained in Irish workhouses, of whom many are approaching the age of adolescence” (CLEC to Under Secretary for the Colonial Department 17 February 1848). Let me extract the salient points from that Report and the correspondence which surrounds it and add a gloss of my own. I’ll put the points in bold and my own comments in italics.

- “1. Her Majesty’s Land and Emigration Commissioners…having been informed that an eligible class of Irish Emigrants may be found among the Orphan Children now supported at the public expense in Ireland, will be prepared to offer to such of those persons as may, on inquiry, be approved, and as may be willing to emigrate, free passage” to New South Wales and South Australia. “None will be accepted who are less than 14 or more than 18 years of age, and the nearest to 18 will be taken in preference.” There were a number of orphans outside this age range. Yet statistically the average was very close to 18. How accurate their age was to begin with, is another matter.

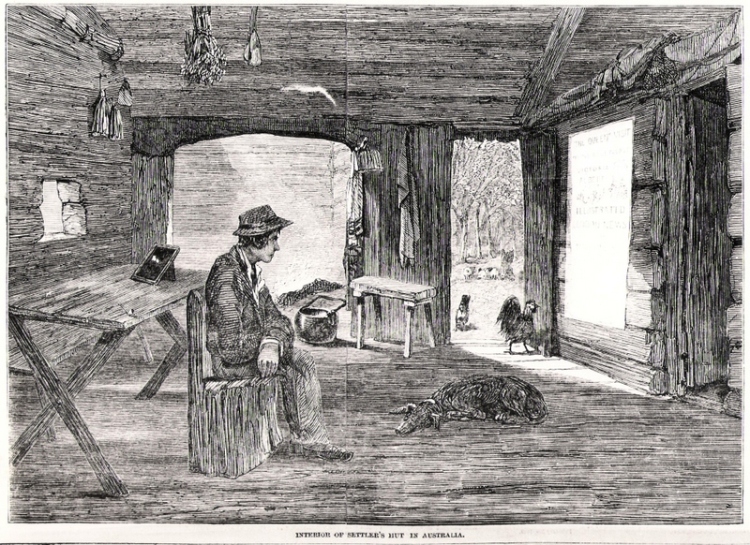

- “2. In order that the persons in question may understand the nature of the advantages thus offered to them, it is necessary…” to tell them something about where they would be going. “The climate both of New South Wales and of South Australia is remarkably healthy, and suited to European constitutions. The soil is good, and produces in abundance, wheat, maize, barley, oats, and potatoes; provisions are much cheaper than in this country; clothing may be purchased at a cost but little in advance of the retail prices here, and the rates of wages at the date of last advices, were in all cases much above those given for the same description of labour in this country. Besides the money wages, Labourers in the country are generally provided with a dwelling and the following allowance of provisions by their employers–10 lbs of meat, 10 lbs of flour, 1 and a half lb of sugar, and 3 oz of tea per week.”

(At this early stage, the proposal included both male and female orphans but by May 1848, just as the first males were being selected, the scheme was restricted to females.)

In order to persuade potential migrants exaggerating Australia’s advantages seems a perfectly natural thing for a bureaucrat to do. It is also what recent arrivals did, anxious to justify their decision to emigrate, both to themselves, and relatives and friends back home. But when the Commissioners answered a letter from Archibald Cunninghame in June 1848 and defended their choice of Irish girls by saying “It was represented to us that the orphan girls in Irish workhouses are generally well brought up, and trained to domestic service”, one has to wonder how much in touch with reality they were. The bureaucrats in Whitehall evidently had little experience of working as a domestic servant in Australia, or living in an Irish workhouse during the Famine. They cut their cloth to suit themselves.

Still, you may well ask, did the orphans have a choice or were they forced to come to Australia? The phrase “…as may be willing” is clearly included in the first point: the Commissioners believed the orphans could choose or opt out if they desired. Put yourself in the position of one of the orphans, what would you do? What would influence your decision?

Our adolescent orphans were people who knew an driochsheal; they had first hand experience of the ‘bad life’, the ‘bitter time’ of the Famine. They were destitute famine victims, famine refugees, if you like. They had fallen on such hard times that they depended on the workhouse for their very survival. For them, the workhouse was the difference between life and death. They were in the care of an eleemosynary institution and hence, orphans. Three quarters of them had no parents still alive, a quarter of them still had one parent (see the dictionary definition of ‘orphan’). They were as the Sydney Morning Herald later put it “deprived by death and pestilence of their natural guardians”. Or, perhaps like 17 year old Mary Early, from Enniskillen, you came into the workhouse suffering from fever and deserted by your widowed father? Or 15 year old Margaret McWilliams, born in Derry, you came into Magherafelt workhouse with your 38 year old widowed mother and three siblings, and described in the Indoor Register as “helpless”.

If the Master or Matron of the workhouse came to you and said, here’s a chance of a free passage to Australia, what would you do? Given the desperate circumstances of these young women, was it really a question of choice?

Yet it would be a mistake to see the orphans purely as famine victims. To do so, would do them an injustice. Who are we to deny them any agency? There were more than ‘push’ factors at work, ‘pushing’ them out of Ireland. Whilst the orphans were less literate than assisted Irish female emigrants generally, 59% of them could read; and where one of them could read, she could read to a number of others. She may even have read in her local newspaper the letter from a settler in Geelong–“On Christmas day I had lamb and green peas for dinner, gooseberry pie and plum pudding. My master sent two bottles of brandy and two bottles of rum amongst four of us in the kitchen”. Or the piece entitled “Life in New South Wales” (4 October 1849) in ‘The Lurgan, Portadown and Banbridge Advertiser and Agricultural Gazette’–“In another part of the country our traveller saw a girl on horseback driving cattle with a stock whip. She bestrode her steed like a man; the gay ribbons of her bonnet fluttered in the wind; and she was arrayed in white pantaloons adorned with large frills. This was ‘a currency lass’…”.

News about the scheme, as it progressed, was also reported favourably in local newspapers. On 9 January 1849, the ‘Limerick Reporter’, for example, had the following paragraph , “This morning fifty young girls selected from the workhouse by the government agent, proceeded to Dublin, en route to Australia. They were under the charge of Mr Scott, the Master, and of the ward-mistresses,and presented a neat, trim and cheerful appearance”. In the local media, and in oral tradition to which the orphans belonged, Australia was an attractive destination. [“The Nation” objected to the young women leaving. Yet its voice was a lonely one. Be careful of a ‘post hoc, ergo propter hoc’ argument, as my good friend Professor Clarke used to say.]

The young women were capable of making up their own mind. Some of them no doubt discussed the matter among themselves in the workhouse. Others would have talked with their siblings and their friends. The perennial attractions for all emigrants–material considerations, the chance of employment and good wages, marriage, and the hope of familial security, better prospects and opportunities, a sense of adventure– surely played a role in an individual orphan’s decision to leave her already broken home.

- 3…The males (see above at the end of bullet point 2) and females are intended to be conveyed in separate ships. Teachers will be appointed to them, and means will be taken to provide for the instruction of the Emigrants in conformity with their respective creeds. This took some time to implement. It was not until early 1849 that vessels carrying mainly Roman Catholic orphans had “clergymen of that persuasion” on board “serving as chaplains as well as religious teachers”. The ‘Irish Government’ insisted that this be the case and there were the usual delays over who should pay. There was also difficulty in finding suitable and willing candidates. The books furnished to the vessels will consist exclusively of those authorized by the National Board of Education. In those of the ships which may carry Orphans, (females), there will be a trustworthy Matron to take charge of the Emigrants, under the direction of the Surgeon, who will be entrusted with the general management of every ship.

This looks all well and good on paper. In reality, it was subject to the vagaries of the human condition viz. how strong a personality the Matron was, the Surgeon’s attitude towards the young women and the dynamics of teenage interaction between themselves and towards authority. This was noticeably problematic in the early vessels.

- 4. The Emigrants’ ships will be despatched…from Plymouth, to which place the emigrants must be conveyed at the expense of the Board of Guardians. Emigrant ships can be despatched from Plymouth only, because it is only at Plymouth (with the exception of London,) that the Commissioners have an Emigrant Depot which will enable them to collect the Emigrants previous to embarkation, and Officers under their control, who can ascertain by inspection that the Emigrants are all in a fit state of health to embark , that their persons are clean, and their clothes clean and sufficient. The calamities which would result from the introduction of any infectious or contagious complaints on board one of these vessels, render this arrangement indispensable.

The Commissioners’ meticulous attention to detail was responsible for the very low death rate among the orphans. It was less than 1%. The orphans were given a clean bill of health by Lieutenant Henry in the workhouse and again in the depot in Plymouth before they embarked. They received decent food on board ship, half a pound of preserved meat on Sunday and Thursday, half a pound of pork on Monday, Wednesday and Friday, half a pound of beef on Tuesday and Saturday, flour, suet, raisins, peas, rice, preserved potatoes, tea, coffee, sugar, butter, water, vinegar, mustard and salt. On board, the surgeons supervised a regime that made sure their quarters were clean and hygienic.

It is worth emphasizing our orphans were not the victims of ‘rip-off merchants’, the runners who exploited the naivety of spalpeens and gossoons from the West of Ireland as they disembarked from their steamer in Liverpool. The orphans were not the victims of free enterprise, make as much money as you can Ships’ captains. Those captains packed as many people as they could on board their vessel across the Atlantic to North America, paying little or no attention to the emigrants’ state of health or food supplies. The orphans’ voyage to Australia was very different from the voyage of their compatriots to North America: Australia did not have a Grosse Isle.

“What do you carry from Ireland

When you leave at seventeen?

Lizzie brought fine linen for her wedding dress

and her mother’s lullaby.”

(Miriel Lenore, “Lullaby’, in drums and bonnets, Wakefield Press, 2003, p.76)

- 5. It will be necessary that each emigrant should be provided with the following articles, which compose the lowest outfit that can be admitted. For Females: Six Shifts– two Flannel Petticoats—six pair Stockings–two pair Shoes—two Gowns, one of which must be made warm material. As a general rule, it may be stated, that the more abundant the stock of Clothing,the better for health and comfort during the voyage. At whatever season of the year it may be made, the Emigrants have to pass through very hot and very cold weather, and should therefore be prepared for both…

- 9. The Board of Guardians will determine whether in order to obtain these advantages, they will provide the Out-fit and conveyance to the port of embarkation on behalf of the Orphans in their respective workhouses, and on their communicating their decision to do so, to the Poor Law Commissioners, an Officer will be deputed by the Emigration Commissioners, in order to ascertain whether they contain any suitable Candidates for Emigration of the above class.

Often one of the interesting things about a historical source is what it doesn’t say. This sort of thing is easy to miss. In this CLEC memorandum, for example, very little is said about who is going to pay for the scheme. Less than a week after the Report Earl Grey wrote to Home Secretary Sir George Grey in very clear language, “…if the Irish Govt will sanction those parts of the arrangements which require their concurrence, his Lordship will be prepared at once to assent to it on behalf of the Colonies of New South Wales and South Australia and will allow the expense of providing passages to these Colonies for orphans properly selected in the manner pointed out by the Commrs, to be paid for out of Colonial funds”.

This was a major bone of contention between Earl Grey and Australian colonists. Grey indeed responded positively to colonial demands for labour but he failed to resolve long standing differences between colonist and Imperial authority over how government assisted emigration be funded and run. Grey aggravated these differences by insisting that Britain retain control over Land funds and hence emigration policy. His Australian opponents would later seize on the female orphan scheme as a means of embarrassing him. In turn, “some of the odium attached to Earl Grey undoubtedly rubbed off on the female orphans”. The orphans themselves were probably unaware they were pawns in this political contest. But it is, I think, one of the major reasons the scheme was so short lived. It was to last less than two years.

Let me stop now. It’s long enough already. I’ll continue with the organization of the scheme in the next post.

Very helpful article, with information nee to me. My gr gr grandmother Jane O’Leary was sent from the Skibbereen workhouse, leaving from Plymouth Dec 31st, 1849. She thought she was going to America with her brothers & that she must have got on the wrong ship in the confusion on the wharf.

She arrived Port Phillip about March 1850 & was indented as a domestic servant to a woman in Geelong. Her grandchildren’s story was that she was only about 14 when she arrived.

Nothing is known of her life before the Skibbereen workhouse. She didn’t know her parents’ names or the date of her birth.

LikeLike

I wonder whether your Jane O’Leary is related to my Ann O’Leary… Ann came to SA on the Elgin (listed as Anne Leary) earlier in 1849, at 16, and the only information I have about her parents is that her father’s name was Timothy. Searching birth/baptism records, I’ve found one record for an Ann born to a Timothy O’Leary (in Co Cork) – her birthplace was in the Macroom poor law union, but I’m wondering whether she may have moved as a child (family searching for work?) and ending up coming via Skibbereen, if I have the correct birth record.

LikeLike

Liz, I’ll see if i can put you in touch with Judith.

LikeLike

This is fabulous as I haven’t been able to find much information. My great great grandmother was on the Elgin with 195(?) girls who arrived in Adelaide in Sept 10, 1849. Also her sister. They were from workhouse in Cronmel.

They were Mary ( 1.11.1836- 19.12.1880) and Brigid ( Bridie) Crimmin as appears on ships passenger list. However, I believe the correct spelling was Crimeen or Cremins a second name given to a few Descendents.

She married William Ellery 4.6.1854 at st Mary’s church Port Adelaide. She had 12 children and outlived half of them.

The children of two of her daughters married and hence my maternal grandparents were first cousins.

I have found no trace of her sister Brigid other than she witnessed Mary & Williams marriage certificate 5 years after arrival. We are slfdriving in Ireland for two weeks this May and will stay a couple nights in Clonmel

LikeLiked by 1 person

Maria,

The Clonmel Board of Gurdians Minute book names fifteen of those who came from the workhouse Clonmel BGMB 14 May 1849 page 306. There is plenty relating to the scheme in the Minute books see 14 april 1849 pp256-72. Mary Crimmin’s name appears 257 as well as p306. You should be able to see these in the Clonmel Library. But best to check beforehand. best wishes Trevor p. s. Have you sent your information to Perry for the database?

LikeLike

Thank you Trevor McCLaughlin for this very interesting post and also for your follow-up note to Maria.

Mary and William Ellery were my great, great grandparents also! I am descended from Phoebe Christina Ellery, their second daughter. I don’t know what the etiquette of this is but I would really like to communicate directly with Maria about this branch of my family tree. Would that be possible?

LikeLike

I’ll email you both at the same time. Maybe type Clonmel into the search box at the end of one of the posts. Best to check too where the CLonmel BGMB are held. best wishes.

LikeLike

As usual Trevor, very perceptive and informative. Wonderful insights.

LikeLike

Thankyou Terry. Did you see Lisa’s comment at the end of Blogpost 47? Her ‘orphan’ came from Belmullet.

LikeLike

Love your work, Trevor. My Ellen Hurley was one of these emigrants, arriving in Port Philip and Geelong, aboard the Eliza Caroline. She married her Employer, John Flanagan, whose wife had died before she arrived.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on trevo's Irish famine orphans.

LikeLike