H.H.Browne

and

(Votes and proceedings of the Legislative Assembly of New South Wales)

1859

REPORT on IRISH FEMALE IMMIGRANTS

A while ago I alerted readers to the importance of this Parliamentary report for the history of the Irish Famine orphans. If you remember, NSW Immigration Agent, H.H. Browne, made such disparaging remarks about Irish female immigrants in his 1854 report he provoked the Sydney Irish community to lobby for a parliamentary enquiry. (See my earlier blogposts, 26, “A NSW Parliamentary Enquiry” at http://wp.me/p4SlVj-BT, and comments I made at the end of post 21 on ‘why the Earl Grey scheme came to an end’, at http://wp.me/p4SlVj-q8 ) As the enquiry got underway, Browne did a quick twostep and claimed he never meant to include all Irish female immigrants, only the orphan ‘girls’. You will thus appreciate why the report, its minutes of evidence and appendices are so important for a history of the Irish Famine orphans. Whatever its limitations, and there are plenty, it is a very important, near contemporary, primary source.

Careful readers will notice I’ve already used the report in a couple of my earlier posts; Mrs Capps, not long after she arrived from Cork, became Matron at Hyde Park Barracks. In her evidence presented to the committee of enquiry, and she was generally sympathetic to the orphans, she recounted the punishment meted out to Barracks ‘returnees’; they being locked in a small room spending their days picking oakum. This was briefly mentioned in post 13, ‘Government preparations Again’, at http://wp.me/p4SlVj-g4. Likewise, some of the sad history of Mary Littlewood, in post 9, at http://wp.me/p4SlVj-dQ, comes from Appendix L; and post 22, concerning the cancellation of orphan indentures, at http://wp.me/p4SlVj-vf , is inspired by the report’s Appendix J.

The information for the last two items comes from the bulky collection of documents that Immigration Agent Browne presented to the enquiry. There were seventeen (17) Appendices attached to the Report, all from Browne, and a number of ‘Addenda’ relating to South Australia’s difficulties coping with a large influx of Irish women immigrants in the mid 1850s. All this material was presented to the enquiry by Browne, to defend himself, and to support what he said when he appeared before the committee.

Historians are very grateful for such important ‘primary’ sources, even if they are biased. I’m reminded of something I said earlier about not accepting everything you read at face value; I’m reminded too of my very first term at Trinity College when the renowned medieval historian J. Otway-Ruthven, told the class, “for every ten minutes you spend reading, spend at least half-hour thinking about what you’ve read”. I can still mimic her voice. Good advice, I think, in these days of ‘instant’ social media. It’s important we read this particular report with our critical antennae twitching. I wouldn’t want to accept everything presented to the enquiry as gospel. Certainly not take it as a true measure of the orphans’ worth. That requires a separate investigation.

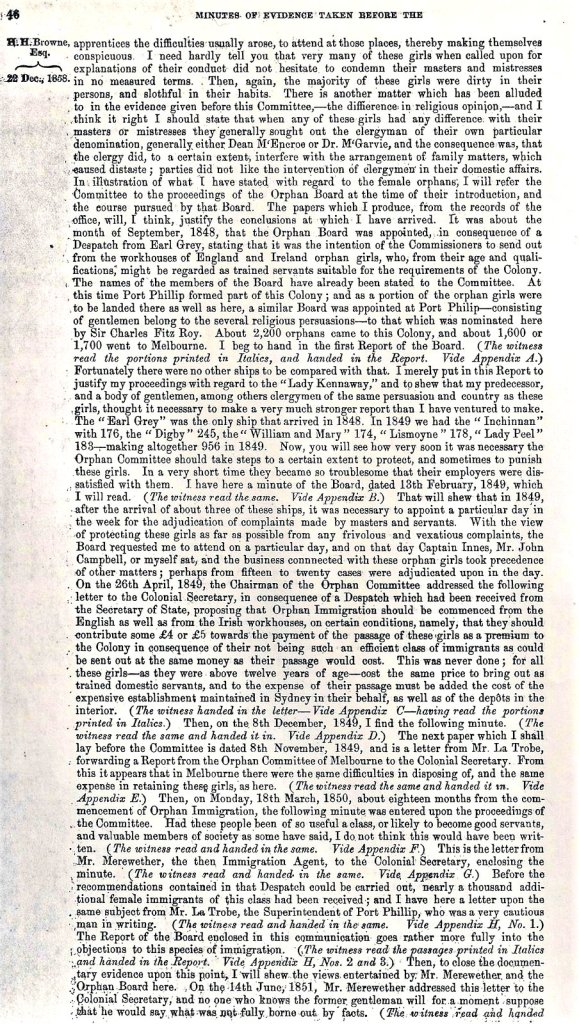

Extract from H.H.Browne’s evidence

Extract from H.H.Browne’s evidence

Let me illustrate what I’ve just said about the need to be critical of primary sources. Browne made sure he handed the committee the first report of the Sydney Immigration Board in 1848 concerning the first vessel to arrive, the Earl Grey. You may remember it was the vessel that carried the infamous ‘Belfast Girls’. His only comment, about a third of the way down the extract above, was, “Fortunately there were no other ships to be compared with that.” Yet, somehow he completely, or conveniently, forgot to mention the report of the Colonial Land and Emigration Commissioners on this matter. Nor did he provide any of the details of C. G. Otway’s report from the Irish Poor Law Commission, a printed copy of which appeared in NSW parliamentary records in 1850! [check date] Nor did he mention Earl Grey’s admonishing Dr Douglass for being too quick to jump to conclusions about the young women in his charge. Strangely, none of the committee members mentioned any of these either. Memories are often short-lived and selective, are they not? Maybe we construct the memories we are comfortable with.

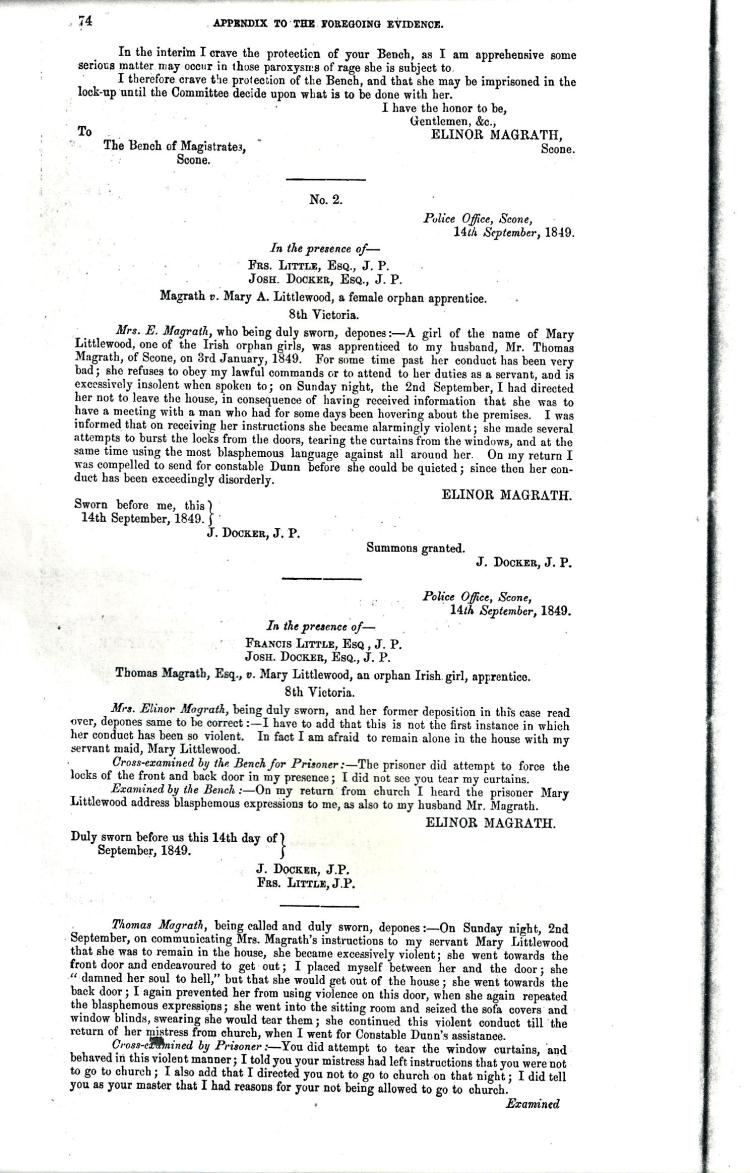

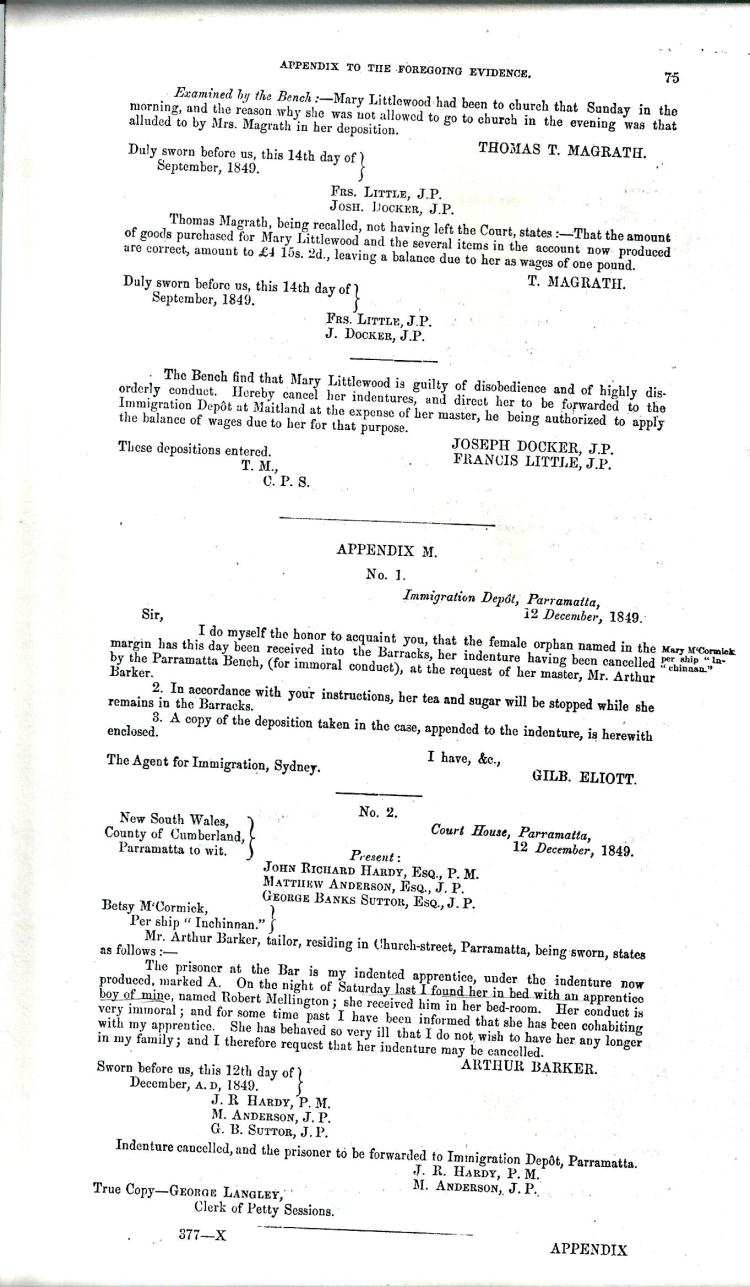

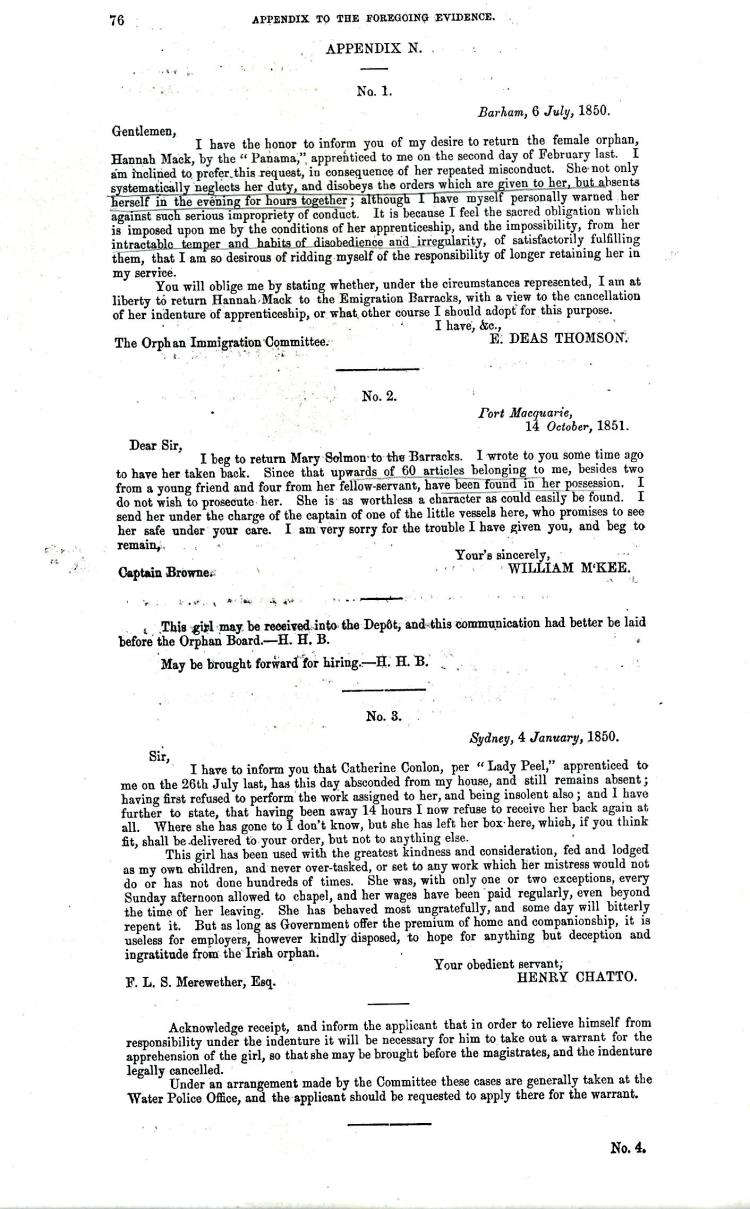

Similarly, Browne carefully selected the individual cases he put before the committee. They were cases where employers had asked ‘to be released of their charge’—Mary Littlewood from Armagh, Betsy McCormick from Galway, Hannah Mack from Mayo, Cathy Conlon from Leitrim and Ellen Maguire from Cavan–because the orphan was a thief, disobedient, intractable, wild, ‘having been found in bed with an apprentice boy’ or given to running away. It is hardly surprising he should ‘select’ cases he thought would justify his remarks that the orphans were “distasteful to the majority of colonists”. Too selective by far, one might suggest. Somehow, too, it escaped him that Mary Littlewood had previously been smashed in the face by her employer on Sydney’s North Shore.

Nonetheless, there is much that is valuable in the material Browne submitted. He gathered together and presented to the enquiry [Appendices C to H] minutes from Orphan committee meetings in Sydney and Melbourne, and letters from his predecessor, Immigration Agent Merewether, and Superintendent La Trobe in Melbourne. These demonstrate the most clearly how early were the official moves to bring the orphan immigration scheme to an end.

As early as April 1849 [remember the scheme only ran from 1848 to 1850] the Sydney Orphan Committee, under the chairmanship of Francis Merewether, warned the Colonial Secretary the ‘Earl Grey orphans’ would be a greater drain upon the public purse than ordinary female immigrants (Appendix C, p.58). And in October of the same year, Superintendent La Trobe, at the request of the Melbourne Committee, urged the Colonial Secretary to send ‘English orphans concurrently’, and to reduce the total number being sent: “the demand for the orphans has sensibly diminished”; “by each succeeding ship” they were “disposed of to parties of a lower rank, and less desirable class…“; that there was a preference for other migrants “on account of the inexperience and incapacity for household work of the orphan girls”; and because they had to follow the regulations of the Colonial Land and Emigration Commissioners, the orphans’ “cost to the Colony” was greater than that of ordinary immigrants. By early 1850 both committees unanimously resolved to recommend “to the Government that the emigration from the workhouses in Ireland should for the present be discontinued“.

Clearly, the orphan committees in Melbourne and Sydney, and indeed in Adelaide as well, played an important part in bringing the Earl Grey Scheme to an end. I have tried to put this ‘official’ position into broader context, elsewhere ( blogposts 21 and 22). Neither Browne nor members of the 1858 parliamentary committee mentioned other factors that helped bring the scheme to an end; the vitriolic, sectarian and blatantly political battles played out in Melbourne newspapers, for example. Nonetheless it was an astute move on Browne’s part to remind both Archdeacon McEncroe and Francis Merewether of this ‘official’ position: both were members of the Sydney Orphan Committee, and both would be called to give evidence before the Parliamentary enquiry in 1858. It not only helped them construct their memory of the scheme but allowed them to tell the enquiry that orphans were paid a lower rate of wages; that they were better suited to rural employment; and that employers should have made greater effort training them as their certificates of indenture required.

Browne was to make much of the large number of cancelled indentures he dealt with as Water Police Magistrate. But members of the enquiry reminded him it was precisely because he was responsible for the Irish orphans that he heard so much about them. There was no such requirement by the colonial government to regulate English, Scottish or other Irish domestic servants in quite the same way. [See also http://wp.me/p4SlVj-vf ]

The modern observer will be surprised by the privileges allowed Immigration Agent Browne and the ways the enquiry conducted itself. At the very first meeting of the Parliamentary committee, 6 July 1858, Browne was invited to attend all their meetings, and if he desired, put questions to the person being asked to give evidence. His would have been a disconcerting presence to say the least. He absented himself when members of the Celtic Association gave evidence. Surprise, surprise. But he was present at all the other meetings, including those abandoned for want of a quorum, and including those where his pointed questions to Archdeacon McEncroe, Daniel Egan and Mrs Capps undoubtedly worked to his advantage.

At the request of Captain Browne, who was present during the examination, the following questions were put to the witness–

(p6) The Ven. Archdeacon McEncroe 6 July 1858

87. By the Chairman: Were you, Mr Archdeacon, a member of the Orphan Immigration Committee? Yes…

88. You attended, I believe, very regularly,? Pretty much so…

90. After eighteen months experience, you were one of those persons who were of the opinion that orphan immigration should be discontinued? I don’t recollect that.

—–

At the request of Captain Browne, the following question was put to the witness by the Chairman–

(p.31) Mrs Capps 4 Nov. 1858

25. By the Chairman: During the period that this immigration was going on, do you know of some hundreds of instances of those girls being returned to you as being unsuitable for their employment? Yes but in some instances it was the fault of the employers; they were very hard upon them. There was always some explanation…

Browne continued to put questions to the witness through the Chairman, George Thornton.

28, 29; Were not some of them so excessively bad that they were placed under the charge of a sergeant of police, in a sort of hard labour department in a building adjoining the depot? Yes a few of them were unmanageable—about twelve altogether.

Did they not sometimes amount to upwards of a hundred, who were occupied in picking oakum to keep them employed? I never knew there was so many as a hundred…

Mrs Capps was not as malleable as Browne would have liked.

—-

I wonder what kind of answers the orphans themselves might have given, had they been asked to appear before the enquiry.

Would they have been all “Yes sir, no sir, three bags full, sir” when they were questioned by powerful, authoritative males? Or do you think they stood up from themselves?

Mary Black; So you couldn’t find the money to look after us famine refugees? Ya never tasted the milk of human kindness? Yer heart not big enough? Nothin’ much’s changed, has it, ya fuckers?

Mary McCann: I’d four kids to look after by 1858. Me and my husband took no notice of any bother. We didn’t know what was in the papers. Himself couldn’t read anyway. We were off to the diggins at Kangaroo Gully.

Bridget Harrington; There was always a crowd of fellas outside church on a Sunday, not all of them young fellas neither. None o’ them found us ‘distasteful’.

—-

Sometimes I think the main purpose of parliamentary enquiries such as this one is to pour oil on troubled waters. In this case, allow Browne to save face, give the Celtic Association an opportunity to air its grievances, and reach a compromise regarding the orphan ‘girls’.

On 19 August 1858, representatives from the Celtic Association, Jeremiah Moore, William Davis and James Hart were given the opportunity to express their disgust at the tenor of Browne’s remarks about Irish female immigrants and to defend the honour and good name of the orphans. But in their polite way of doing things, they insisted they were moved by ‘no personal hostility towards Mr Browne‘. Previously, in July, John Valentine Gorman, a notable Sydney merchant and auctioneer, and signatory to the Association’s petition, told the enquiry, he thought, as per the petition, that he would be giving evidence about Irish Female Immigration generally, and ‘not any particular class of it’, viz. the orphans. Some of the petitioners’ thunder had been stolen. Politics can be a sly and dirty business, can it not?

The enquiry stumbled forward, until nearly three months later, in early November, its committee met again. But now it had become smaller; Donaldson and Parkes no longer attended. On the 4th and 5th November it interviewed the Honourable Francis Merewether Esq MLC and Mrs Capps and Pawsey, both of whom kept Female Servants’ Registry Offices in Sydney. It would be another forty seven days and five attempts to reach a quorum before H.H. Browne himself was called. He had been given plenty of time to prepare himself and gather documentation for his own defense. Despite being closely questioned by Daniel Deniehy who exposed contradictions in his statements, Browne always managed to wriggle free and save face.

(p.51) 22 December 1858 57. By Mr Jenkins: In your replies to the questions of Mr Deniehy, when he wished to obtain from you the meaning you attached to the word “distasteful” , I understood you to say that the word referred to the system—that of apprenticeship? The system had a great deal to do with it; because under the agreement the employer could not get rid of a servant without going before a Police Bench, and he would rather submit to inconvenience than submit himself to annoyance.

58. Apart from the system of apprenticeship, do you think orphan female immigration as desirable as other female immigration? Certainly not; I would not have recourse to any workhouse immigration. I think it is not a desirable class.

Thereafter the committee retired to consider the evidence it had gathered. In late January and early February 1859 they convened again to draw up their report. It was now in the hands of a small, intimate, in-house committee, consisting of only four or five men; George Thornton, Mr Deniehy, Mr Faucett, Mr Rotton and Mr Jenkins.

What decision did these five come to? What did their report contain?

You might like to read it for yourself. It is available via Trove in the Sydney Morning Herald, 10 February 1859, page 5 col.6 http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/page/1492527?zoomLevel=1

Here is a brief summary.

- The Immigration report [1854] petitioners complained of, it should be noted, was signed not just by Agent Browne but by two other members of the Immigration Board as well.

- An expression used in that report which was complained of by petitioners, referred not to all Irish female immigrants but to Irish Orphan Immigrants alone. The expression was not specified in the Report.

- Petitioners also complained of the slur made against the moral character of Irish female immigrants. At the beginning of the enquiry, Agent Browne denied intending any such slur. The Committee believed this to be true. And asserted ‘the character of Irish Female Immigrants’ was ‘equal to any other class of female immigrants’.

- Many Irish females may not have been suited to upper-class urban domestic service when they arrived but trained properly they could aspire to that service.

- The Orphans in particular may not have been suited to urban domestic service but they were sent out ‘at a season of particular want and affliction in Ireland‘ and ‘accepted by the local government as apprentices to the vocation of domestic servants‘, and paid a much lower rate of wages than other servants. And because they were indentured, any cancellation of their indenture was required to be officially noted. They thus appear more prominently in the records.

- Finally, the committee recommended the establishment of depots in Southern, Western and Northern districts to which suitable immigrants might be sent in the future.

Not everyone would be satisfied by their Report. Some would have preferred H. H. Browne be censured. But yes, that sound you hear is of hands being washed and the Famine orphans being consigned to history.

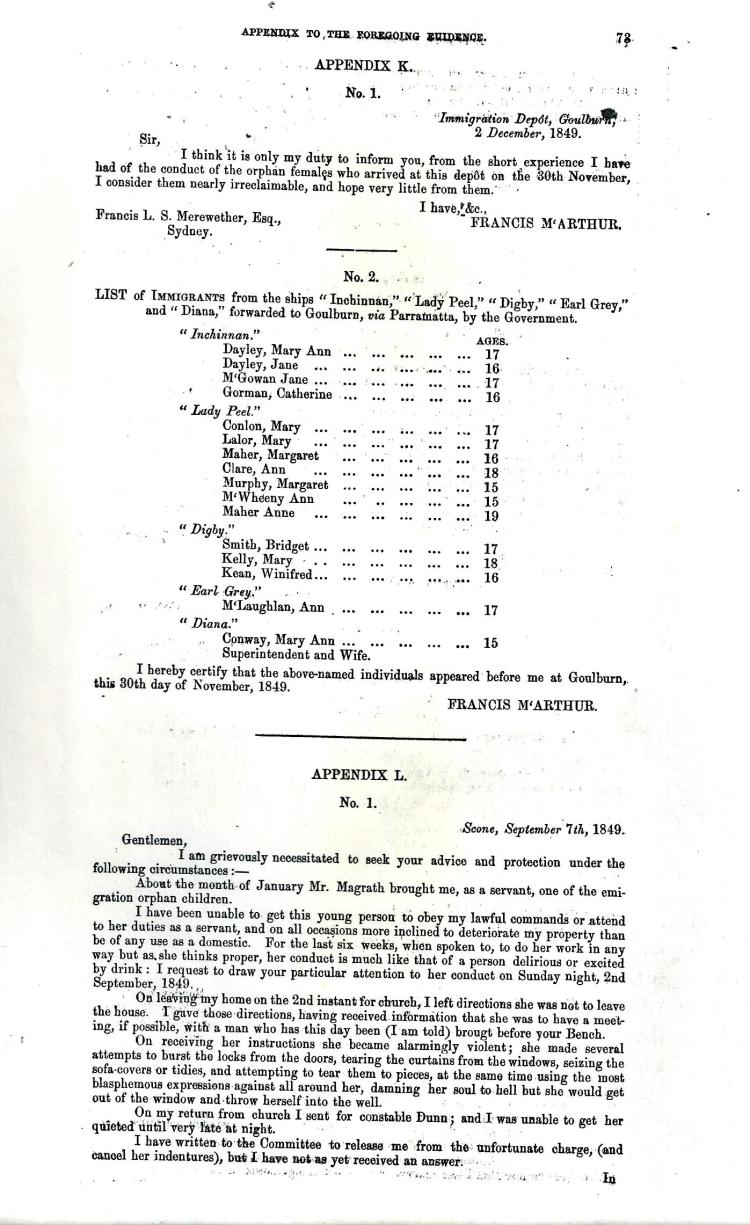

Extract from the appendices to the Report most of them submitted by H. H. Browne.

I have included his ‘selective’ submission re Mary Littlewood per Earl Grey. See below

Appendix L. I’ve written about her in Post 9. see https://wp.me/p4SlVj-dQ

Another great blog. Thanks Trevor

Perry

LikeLike

Thanks Perry. Had a look at some of it lately and thought much of it needs a drastic revision.

LikeLike