Some Unfinished histories (1)

Mary McConnell

I’m not sure how this will go. I’ll try getting in touch with some of the orphans’ descendants who sent me material in the past. Maybe together we can give an outline of a family history that may be of interest to others, even if it’s just to suggest possible lines of enquiry. I’ll attempt some of the things I’ve suggested earlier, such as make our own presence felt, find something about the orphan’s Irish background, as well as what happened to her in Australia. And I hope, put her in some kind of historical context. I’m sure you know all this already. You are welcome to make a suggestion about the things we ought to include.

This time, I’ve chosen to write something about one of the infamous ‘Belfast Girls’, Mary McConnell. I’ve been in touch with one of Mary’s descendants, Mrs Pat Evans, for more than twenty-five years; she herself has been working on Mary for more than thirty. Tricia has provided lots of information about Mary’s history. She tells me that she is emotionally close to her orphan descendant. After all, she is her great-great grandmother. It took her a while to reconcile herself to some aspects of Mary’s life but she understands her, and admires her resilience. Tricia says, ” I am able to accept that my Mary was not what we would call a good girl today and at the same time extremely thankful of what she did to survive in the harshness of the day”.

We both are very grateful to a renowned local historian, Brian Andrews, who helped us put Mary’s life into context, in the Hunter Valley of New South Wales. Unfortunately I lost contact with Brian some years ago. But I see, via the web, he was awarded an OAM for his work as a local historian. Congratulations and well-deserved, Brian. Brilliant work.

I’d like to keep this post in an unfinished form to emphasize that orphans’ family histories are constantly being revised. The ‘facts’ can change so quickly.

Tricia rightly suggests that if she was writing Mary’s history outside and independent of this blog, she’d provide a summary of the Earl Grey scheme, something like the following. So , in Tricia’s words,

“Lord Earl Grey, the British Secretary of State, thought he had the magic answer for several problems facing the English Parliament. He could rid the Irish workhouses of the orphaned paupers by supplying the Colonies with female labour and females to correct the imbalance of the sexes, which were both needed in great numbers in the Colony of New South Wales. This scheme was called the ‘Earl Grey Scheme’ and was to remove about 4,000 female Irish orphans from the disgusting workhouses throughout Ireland. The scheme was to survive for only two years.

See http://www.workhouses.org.uk/Belfast/

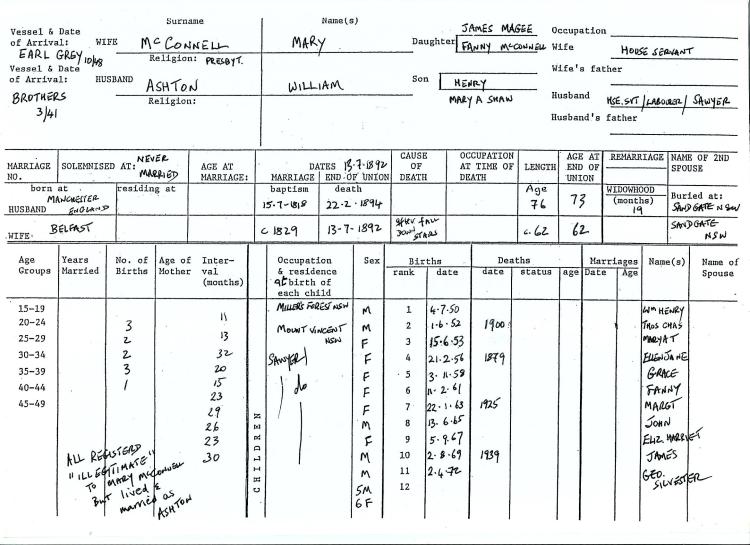

Tricia recently informed me that William Ashton‘s details are also incorrect. He was not a Bounty migrant who came by the Brothers in 1841. Rather, he was a convict found guilty of highway robbery at Liverpool Quarter Sessions in July 1838. He arrived in New South Wales on board the Theresa in 1839. Tricia discovered this through Maitland gaol records and the Maitland Mercury which linked William and Mary’s name together. We should also remove William’s parents’ names and his birthplace and date from the form, and change his occupations to ‘brickmaker, sawyer, labourer, and bushman’. The other details are correct.

Among descendants of the Famine orphans, the story of the “Belfast Girls” is relatively well-known. Surgeon Douglass described the ‘Belfast girls’ as “notoriously bad in every sense of the word“. “The professed public woman and barefooted little country beggar have been alike sought after as fit persons to pass through the purification of the workhouse, ere they were sent as a valuable addition to the Colonists of New South Wales”. It was a stain that’s been very difficult to remove.

A detailed enquiry by Irish Poor Law Commissioner C. G Otway rebutted Douglass’s claims –as might be expected– and was supported by the Colonial Land and Emigration Commissioners in London–as also might be expected– but it was never enough to restore the good name of the rebellious ‘millies’ (Mill workers) and “gurriers” from Belfast.

As far as the Surgeon, Captain, and Matron of the Earl Grey were concerned, Mary McConnell was “a professed public woman”. She, and the other ‘Belfast girls’, should not be allowed to land in Sydney. “Considering that the landing of the Belfast girls in Sydney, would assuredly lead to their final ruin, and being also impressed with the importance of separating them from the remainder of the Orphans, the Committee [the Sydney Orphan Committee] acceded to the proposal of Dr Douglass, that they should be at once forwarded into the Country” .

Let me mention in passing, how much I enjoyed Jaki McCarrick’s recent award winning play, “Belfast Girls“, not as a nitpicking historian but for its dramatic sensibility, its contemporary relevance, and above all, Jaki’s sympathetic treatment of the young women.

Ellen (with renewed resolve) …Remember, this is what you’re to be wed ta. Your books. Your learnin’. For Molly’s sake — let none of us waste this journey an’ all we’ve learned. You — in here (points to her head) are a great gift to Australia, an’ don’t ya forget it. We all are an’ must none of us forget it.

(Belfast Girls by Jaki McCarrick © Samuel French Ltd. London. All rights reserved

Reprinted by permission of Samuel French Ltd. on behalf of Jaki McCarrick)

——————————————

We are lucky the Otway Report has survived: it has specific information about Mary McConnell. (For more details, see Disc 2 of Ray Debnam’s CD set, Feisty Colleens).

In the report, two Belfast Detective Police Constables, DC John Cane and DC Stewart McWilliams testified that none of the Belfast girls accused of prostitution by Surgeon Douglass was known to them as such.

Stewart McWilliams, Police Constable sworn:

I am one of the detective police;…I have been so employed for the last eighteen years; from the nature of my duties, I have a knowledge of all the houses of ill-fame, and the persons frequenting them in Belfast; all of the prostitutes I mean. I do not think there is a prostitute in the town I do not know…

From my knowledge of young persons working in mills and manufactories, I know they are generally unguarded in their language and mode of expression, and use unchaste language, though they may not be unchaste in person, or prostitutes.

I have read over the names on the list of the females sent in the first vessel from Belfast, and there is not the name of a single person that I ever knew or heard of as being a prostitute amongst them.

Look at the name whose initials correspond with Mary McCann, No. 45 I had no knowledge of her as a prostitute or person of bad character, and she could not have been well known in Belfast as a prostitute without my knowing it.

Look at Mary McConnell, No.55 I give the same answer… (Barefoot vol. 1, pp. 106-7.)

Given the circumstances, theirs is the kind of evidence we might expect? I leave you to decide for yourself. My view is that people today are not so quick to adopt the high moral ground; they understand how someone may depend upon prostitution to survive and others might use it for their own empowerment and material security. Maybe Surgeon Douglass too quickly accepted as truth the insults and obscene language the Belfast orphans hurled at one another.

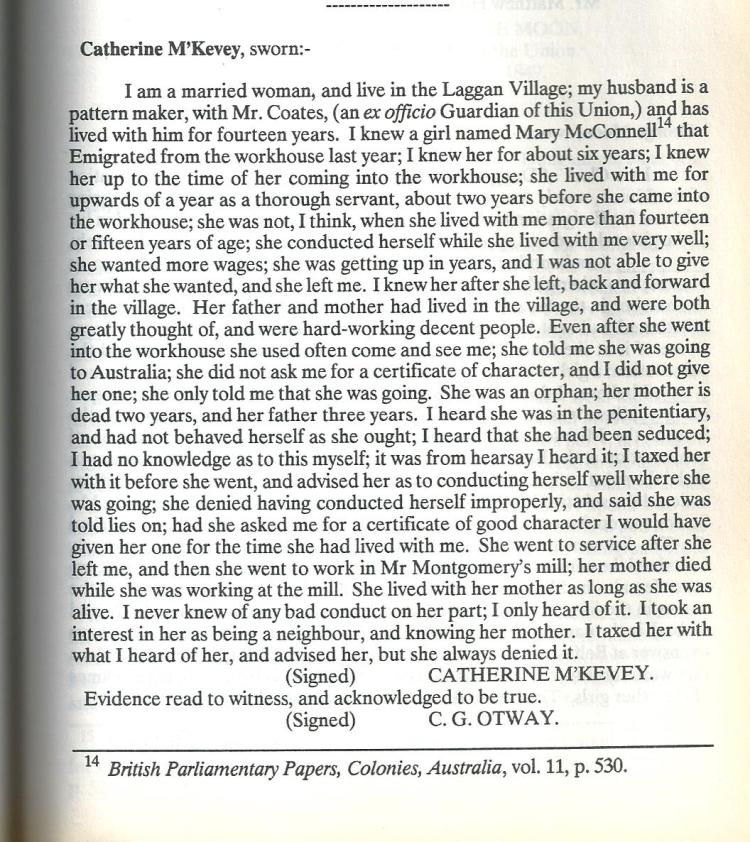

More interesting than the Constables’ evidence is the testimony of Catherine McKevey who lived with her husband, a Pattern Maker, in Laggan Village. She had known Mary personally for the six years before she left for Australia.

This has an authentic ring to it, does it not? Mary’s parents were ‘decent, hard-working people‘. Mary had lived and worked with Mrs McKevey for about a year when she 14 or 15 years of age, as ‘a thorough servant‘ (i.e. doing everything). Her dad had died three years ago (in c. 1845-6) and her mum two (in c. 1846-7); ‘she was an orphan‘. ‘I heard (gossip) she was in the penitentiary and had not behaved herself as she ought‘. After Mrs McKevey’s, Mary had gone first into service, and then to work in Mr Montgomery’s mill. ‘I…advised her as to conducting herself well where she was going…‘.

—————————-

Good-bye your hens running in and out of the white house

Your absent-minded goats along the road, your black cows

Your greyhounds and your hunters beautifully bred

Your drums and your dolled-up Virgins and your ignorant

dead

(Louis MacNeice, Valediction)

—————————————

Sometimes family historians need to make an educated guess about what happened to a descendant. We’ve done that in some of what follows.

Mary was born in Tyrone, the daughter of James and Fanny McConnell, and baptised a Presbyterian. Surely she had siblings? Maybe a brother or sister died before she and her young parents went to Belfast, in the early 1840s. ‘Jummie’ McConnell, a weaver, part of the declining domestic-putting-out system in Tyrone, and like an ever increasing number of others, was told there’d be a job and hope in Belfast. It was a city built on mud flats, and already growing into Ireland’s major manufacturing city. But in the 1840s, it was a mere fledgling of what it was to become later in the nineteenth century.

The young family went across Queen’s bridge to Laggan Village, down near the Short Strand and the bottom of Ravenhill Road, in County Down. It was part of Ballymacarrat, a largely working-class and Protestant area, with its Iron Works, Vitriol Works, Rope Works and Textile Mills. Tricia was informed by a Senior Research Fellow at Queen’s University that Laggan Village was on the South Bank of the Lagan River, a Protestant working-class area that included Ballarat Street, Dungevan Street and Bendigo and Carrington Streets. The map Tricia has is a fairly modern one; it includes Albertbridge, one of the bridges crossing the Lagan but that bridge was not finished until 1890. In the recent ‘Troubles’, the area was a ‘narrow ground’, a battleground for sectarian conflict. It has since been rebuilt. I doubt if Mary would recognize it, if she returned today.

“I never saw a richer country, or, to speak my mind, a finer people; the worst of them is the bitter and envenomed dislike which they have to each other. Their factions have been so long envenomed, and they have such narrow ground to do their battle in, that they are like people fighting with daggers in a hogshead” (Walter Scott 1825)

Mary appears not have carried any of that ‘venom’ with her. Her common-law husband, William Ashton, was a Roman Catholic and her children were baptised in the Church of England.

Her parents, Jimmy McConnell and his wife, Fanny, were ‘hard-working, decent people’. But Belfast would be no earthly paradise, and Laggan village would be their deathbed.

Tricia, I’ve tried to find out a bit more about Belfast during the Famine years. I haven’t bought this book, just seen bits of it via Google; Christine Kinealy and Gerard Mac Atasney, The Hidden Famine. Hunger, Poverty and Sectarianism in Belfast, 1840-50, Pluto Press, 2000. (The authors also have a chapter in the Atlas of the Great Irish Famine). They explain Belfast did not escape ‘the devastation triggered by’ the Famine which is something not widely recognized by historians. Nearly 1500 people died in Belfast workhouse during 1847 (Mary would have seen many of them die).

In the three months between late December 1846 and March 1847, during a very bad winter, nearly 280 thousand quarts of soup and 775 cwt of bread was given to the hungry through Belfast’s soup kitchens. “By the end of March, over 1,000 “wretched-looking beings” each day were receiving free rations of bread and soup at the old House of Correction“. The Belfast Relief Committee knew that more than food was needed.”There are to be found a vast number of families…who have neither bed nor bedding of any description–whose only couch is a heap of filthy straw, in the corner of a wretched apartment”.

Now imagine you are 17-18 year-old Mary McConnell in late 1846, early 1847. Your dad died a year ago and you and your mum have survived, only just. In that desperately cold winter, your mum died too. You lost your job in the Flax Mill. What would you do? What do you think Mary did? Fight tooth and nail, as a street kid? Become a prostitute, at seventeen years of age? (that is still uncertain). Develop an obscenely sharp and cutting tongue to protect herself from rivals and predators? “That’s my fucken crust of bread, wee lad. Touch it and I’ll cut yer balls off”. Use soup kitchens; there was one in Ballymacarrat. Get into the workhouse when the cold months came. She was in Belfast workhouse “16 months previous to her emigration“, that is since early 1847 (Barefoot, 1, p.71). But then she learned of the Earl Grey scheme, and with other street-wise young inmates, decided Australia was the place to go. Some of her shipmates, the Hall sisters, Rose McLarnon and Eliza Mulholland also had an association with Ballymacarrat.

Pingback: ‘Paris green’ and the story of young Albert Cyril Ashton | Tinteán

Reblogged this on trevo's Irish famine orphans and commented:

In honour of Jaki McCarrick’s play, “Belfast Girls”. See visitqueanbeyanpalerang.com.au

LikeLike

Hi Trevor, I have included your blog in Interesting Blogs in Friday Fossicking at

http://thatmomentintime-crissouli.blogspot.com.au/2016/04/friday-fossicking-april-29th-2016.html

Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks heaps crissouli. That’s a very useful blog of yours. Oops I see you’ve robbed me of a ‘C’ in my surname. Best wishes trev

LikeLiked by 1 person

I found it, the missing ‘C’, it must have been hiding… did that work? 😇

I am sorry, bad proof reading on my part. I’m enjoying reading your blog as well. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi again Trevor; I’ve noticed in your blogs many references to very useful books, most of which are Australian. Are you aware of one written from an Irish perspective by a Ballyshannon researcher, Anthony Begley, published in 2014? It is called, From Ballyshannon to Australia, written at the time of the unveiling of a lovely memorial erected in honour of the 19 girls from that workhouse who left on the Inchinnan in Nov.1848. A very useful book, just over 60 pages but with many great coloured photos. He has a website:- ballyshannon-musings.blogspot.ie/

LikeLike

Thanks Bill

LikeLike

Hi Trevor; it is OK to leave my original comment. It might get the attention of some relatives that I have never met or know nothing about and so broaden my knowledge of my Orphan Girl, Margaret Sweeney.

LikeLike

Trevor I am wondering if in your blog posts you have covered any of the orphans from the Lady Peel arrived 3 July 1849 in Sydney? I tried the search bar without any success. I can’t add anything to your store of knowledge, but I did stumble across two sisters on my cousin’s family tree. Catherine and Mary Foley from the Workhouse : Leitrim, Carrick on Shannon (sourced from the Irish Orphan Database). Seems they both managed to get their employers off-side once out here 🙂 Anyway, if you could point me towards any relevant blog posts that would be interesting, regards Gwen Wilson

LikeLike

ps I can of course, tell you what my research has revealed about who they married, and what children they had, if that is of interest for your project. Gwen

LikeLike

Lovely to hear from you Gwendoline. any news is most welcome.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great. I’ll put something together soon. They set down roots in the Bathurst / Rockley area and had many children. Neither is related to me, and only distantly to my cousin so there will be other researchers much closer to their stories.

LikeLike

Gwendoline, If you have a look at the comments on the ‘About’ page you’ll notice a recent one from Peter where he mentions the Lady Peel. Maybe leave a comment for him there and hope he reads it??

Post 7c …last two thirds of it will give you an idea about the voyage. There may be a Surgeon’s report of the Lady Peel in NSW State Records. It would be worth checking.

cheers

LikeLiked by 1 person

thanks I’ll check it out soon

LikeLike

Hi Guys, I guess I’m the ‘Peter’ that Trevor is referring to. His replies to me have been so helpful & given me an absolute boost in tracking down the right sources. Woohoo! I’m having a whale of a time in unearthing information about my ancestor Eliza Fitzpatrick who arrived in Sydney 3 July 1849 on the Lady Peel. She was in the Athy Workhouse. The Athy Heritage Museum has been brilliant in its advice. I’ve found Eliza’s baptism in the Irish Catholic records on line. I was going to ask Trevor or Perry at the Irish Irish Famine Museum in Sydney whether they knew of any ship’s diaries for the Lady Peel’s voyage. I’ll search that out. In fact I’m also discovering quite a bit about another Famine orphan Ann Trainer who arrive in Melbourne 25 February 1850. She was in the Magherafelt Workhouse. I’ve had brilliant help from the Maghera & District Genealogical & History Society. Members on its Facebook page have given me a number of links to search. I think I’ve found Annie’s natural father through Griffiths Valuations & location of his property. I have a number of family lines i’m working on & I have to pause & write up my findings. All very exciting.

It pays to keep trying various word-search combinations on Google. I tried ‘Henry Parker drayman’ & found a wealth of researched information about his wife Eliza Fitzpatrick & their/her various children. One of them Mary Ann Parker was an inmate of the Newcastle Industrial School for Girls. There could well be other Irish famine orphans or offspring at this institution. It’s incredibly well-searched. The references have led me to lots of newspapers accounts which for some reason never showed up when I did Trove Newspaper searches.

Cheers, Peter

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Trevor

I have been looking at your site for quite some time now and find it most interesting and very informative. I have seen that in today’s post (32) you mention a Brian Andrews from the Hunter. You wrote that you have lost contact details so this may help you.

My wife and I were fortunate to meet Brian last year when we attended a family reunion for the CLARK/Kelly family at Largs. We met him at the Weston Historical Society. I think he is failing a little bit but still OK. I have known the family for many years. In fact we are related to him through his mother, Ellie who was a Landrigan.

In fact his parents retired to Evans Head, a lovely little fishing village just south of Ballina. His first cousin, Jim, was a bookkeeper/accountant for us in our business for some years until he died of cancer. Two of Dad’s aunts married the same Jeremiah Landrigan (Annie died about aged 32). Together there were 10 children. As well, a Mary Landrigan married into our Kelly family from the Hunter.

Brian was a wealth of info for us in our research for my wife’s family, the Lynn family of English origin, in the late 1800’s, coal miners originally.

Brian’s phone is:- 4937 4418

If you have trouble finding him, he has a niece named Jennifer Collier, 4933 8990.

I am descended from Margaret Sweeney, from Ballyshannon workhouse, came out on the INCHINNAN, 1849. There are very many descendants now. Her son and second child, Edward Dougherty is my great grandfather. One of my ambitions is to find a photograph of her. Still no luck, even though she died in 1904. A gem I did not come across, quite fortuitously via an unrelated source, a real coincidence, is a small card sent to a priest to say masses for her daughter who died in her late teens. Her name was Margaret Dougherty as well. Her mother has signed it as Mrs Dougherty so I have an original signature of hers on which is dated her daughter’s death, 19th May 1889. I assume it was written not long after that.

If it interests you, I could scan it and email it to you.

Brian Andrews is a lovely man who I suspect was thoroughly deserving of the OAM.

I hope this info is useful and that I have not bored you with my ramblings.

Kind regards

Bill McDermott

LikeLike

Lovely to hear from you Bill and thank you for all the information. I hope it’s ok to allow others to read.

You wouldn’t happen to have Brian Andrews’ email address? Would you like to scan the signature and put it here so others can see it? Let me know if you have trouble doing that. best wishes

trevor

LikeLike

Oops – did not think that my comment would go public, but no harm done. I just noticed that I incorrectly added the word “not” when I was referring to the “gem” which I have. I will send it to you via email and you may be able to add it in. I do not have Brian Andrew’s email. I will contact some family members or Brian himself to get it. Also when I mentioned Weston Historical Society, I should have written, Kurri Kurri, even more specifically, the Coalfields Heritage Group, beside the High School. Thanks for your interest and reply.

Bill McDermott

LikeLike

Thanks Bill. I’ve removed your earlier message.

LikeLike