CANCELLED INDENTURES

One of the things I ‘d love to do is put the young Irish Famine orphans at the centre of their own story. It would mean looking differently at the sources we have. Maybe it’s beyond this aging, increasingly discombobulated male. Old methods are also still valuable. The first thing I learnt as a history student many, many, years ago, was to examine the source I was using–where did it come from? How authentic was it? Was it reliable? If it was a document, who wrote it, and why? What was its purpose, what barrow was the author pushing, what axe did he or she want to grind? There’s no such thing as an unbiased source.

I’m beginning this post with Appendix J Return of Cases of Orphan Female Apprentices whose Indentures were cancelled, by the Court of Petty Sessions, at the Water Police Office [in Sydney]. It is part of the Votes and Proceedings of the Legislative Assembly of New South Wales Minutes of Evidence taken before the Select Committee on Irish Female Immigration, 1858, pp. 373-450. The Legislative Assembly also ordered it to be printed in February 1859. I know some people may have trouble finding it, so I’ve scanned the whole of Appendix J. I’m sure a librarian in your State Library will help you too, should you wish to see more of the evidence.

Appendix J is a submission made by Immigration Agent H. H. Browne to a New South Wales Parliamentary Enquiry. The Enquiry was a result of a Petition by the Celtic Association complaining about the Agent’s remarks in his report for 1855, concerning Irish female immigrants. Browne had claimed Irish female immigrants were “most unsuitable to the requirements of the Colony, and at the same time distasteful to the majority of ‘the people'”. In other words, the ‘Return of cases of cancelled indentures’ is part of Browne’s defense. It would be worth a close scrutiny at some later date.

Below is the Appendix in full. You should be able to read each page in turn by clicking, or doing whatever you do with tablets and ipads. There are eight pages, listing 254 cases in all. Browne did not become Immigration Agent until mid 1851. Before that, he was a member of the Sydney Orphan Committee and Water Police Office Magistrate. In other words, he was the Magistrate who presided over the cases listed here.

As the observant Surgeon Strutt noted in his diary, on Friday 3 May 1850, “Went to the Water Police Court to hear the complaints made against the orphan girls. Six of them were summoned and one mistress for harsh treatment, but the tone of the Magistrate was against all the girls…”.

Appendix J

Newspaper reporters of the day were strongly influenced by the political ruckus surrounding the Earl Grey Scheme. No doubt they were influenced too, by gossip, rumour, and innuendo, some of which came from the Water Police Office late on a Friday afternoon, after Browne had finished with the orphan cases. Petty sessions court reports, a standard feature of major colonial newspapers such as the Sydney Morning Herald or the Argus in Melbourne and even local, country, newspapers, were full of stories about individual female orphans in 1849, 1850 and 1851. The Sydney cases listed above were not reported in the Herald as often as cases from other Courts of Petty Sessions, in Parramatta, Windsor, and Penrith, for example.

Let me examine one particular case, the case of Francis Tiernan. It may alert you to different ways of interpreting evidence. Remember, just as there were specific legal requirements before a person could be incarcerated in a mental asylum, or before a divorce would be granted, so too, there were specific legal grounds for cancelling indentures. “Insolence” or “disobedience”, “improper conduct”, “absconding” and “neglect of duty” on the part of the apprentice, or servant, were permissible legal reasons. Have a look at the ‘nature of charge’ column in the lists above. See also the apprenticeship agreement at the end of my blogpost 13, http://wp.me/p4SlVj-g4 for information about the obligations of both master and servant.

Reading against the Grain: the case of Francis Tiernan

Here’s the case I want to examine; it’s a report of proceedings at the Court of Petty Sessions in Parramatta, from the Sydney Morning Herald, 4 January 1850, page 3.

Irish Orphan Girl—FRANCES TEARNEN (Tiernan),

apprenticed to Mr John Kennedy, appeared

before their Worships, Mr Hardy, P. M., and

Dr Anderson, J. P. The girl’s behaviour be-

fore the Bench clearly indicated her character.

Mrs Kennedy deposed that the girl was impu-

dent in the extreme, and informed her (Mrs.

K.) that she would not stand at the wash tub

unless she was allowed to wear patent leather

shoes; she was in the habit of beating and ill-

using the children, and with showing her mis-

tress sundry five-shilling pieces, stating she

had received them from single men; also, that

Frances had expressed her determination to be

married, and be her own mistress. Mr Ken-

nedy stated he cold not keep the girl, and the

indentures were cancelled.

Putting aside the reporter poking fun at Frances’s desire to wear inappropriate shoes at the wash tub, what do we see? Surely, you might say, Frances was guilty of ‘improper conduct’ and her indentures should have been cancelled.

Now what happens if you read the report ‘against the grain’, not as the reporter wants you to read it but if you put yourself in that young Famine refugee’s shoes? What stands out? “I’m going to get married and be my own mistress”. I won’t have to submit to this life of drudgery or obey your stupid commands, your bossiness, and your snotty children who deserve the smack around the ears I give them. I have men friends who want to marry me. I’ve never before had money to spend on myself and buy what I like.You don’t know what it was like in Longford when there was no food, and the workhouse was so crowded people were dying like flies. http://www.workhouses.org.uk/Longford/ I swear you have no idea what happened on board our vessel, the Digby. The Captain was a right bastard. I had to protect my poor wee sisters all the time.

I’m suggesting there are different ways of reading the evidence. To counteract the ‘official’ ‘establishment’ view, I’m suggesting, put yourself in the shoes of the Famine orphans, see things from the viewpoint of the young women themselves.

Some time ago, in the introduction to Barefoot vol.1, I wrote the following,

‘…indentures cancelled on grounds of the orphans’ absconding, insolence, misconduct, negligence or disobedience are not simply evidence of the orphans being ‘improper women’ ‘unsuited to the needs of the Colony’. Such evidence might also reflect the young women’s resistance to being treated as drudges by ‘vulgar masters who had got up in the world’. [Archdeacon McEncroe at the 1858 Government Enquiry] It might reflect the young women’s ‘culture shock’…

Undoubtedly, too, both master and servant tried to work the ‘system’. The protection offered the young women by colonial officials encouraged employers to complain the more. Masters thought they could return their unruly servants to… Barracks, forgetting that they were already compensated for the orphans’ ignorance of domestic service by the low wages they paid. Masters’ dissatisfaction was also fuelled by the bad press the young women received. “They had been swept from the streets into the workhouse and thence to New South Wales’; they were ‘Irish orphans, workhouse sweepings. ‘hordes of useless trollops’, ‘ ignorant useless creatures’, a drain upon the public purse who threatened to bring about a Popish Ascendancy in New south Wales…

In turn, the young women, hearing of better conditions elsewhere–higher wages, a kinder master or mistress–knew full well that insolence or neglect of their duties was the means of terminating their employment. Cancellation of their indenture by the Magistrate at the Water Police Office in Sydney, a return to Hyde Park Barracks before being forwarded up the country to Goulburn, Bathurst, Bega, Yass or Moreton Bay may have been preferable to remaining in their current position. It was a gamble many were willing to take’.

Now if I had the energy, or the talent, I’d unpick this argument and develop it some more. To repeat, I’m trying to insist we view what was happening through the eyes of the orphans themselves. What explains the orphans’ relatively high rate of cancelled indentures?

Culture shock

Let me try to develop something I mentioned briefly in that quote above, viz. the culture shock the young women must have experienced. What kind of culture clash upset their well-being? In the example I used in that quotation from the introduction to Barefoot 1, I drew attention to the anger, and anomie, and frustration, of young Mary Littlewood. (See my post 9 http://wp.me/p4SlVj-dQ )

But there were other things as well, things that every migrant experiences to a greater or lesser degree–how to feel your way, how to keep your identity, and yet adapt to your new society. Our young Famine orphans, however, were different from this. They felt the usual uprooting and confusion more acutely than others. They were first and foremost refugees, refugees fleeing a society torn apart by a tragedy of monumental proportions. They were young females without the ‘normal’ support of family and ‘friends’. They were adolescents whose religion and ethnicity was at odds with many members of their ‘host’ society. The figures in authority who were to give them guardianship and support–Orphan Committees, Sisters of Mercy, Matrons in Immigration Barracks–were not always people with whom the orphans could easily communicate. They more likely trusted their shipmates.

What do youse think you’re doin’, dressin’ up like a wee tart Ellen Lynch? Where’d ya get those clothes an’ those silly flowers?

Jealous Missus? Your old man has nuthin’ for ye. He just loves the drink. I’m goin’ to see ma frens an ye can’t stop me.

C’mere ya cheeky wee hussy. I’ll box yer ears. You’re going nowhere. C’mere. C’MERE. ELLEN. I’m warning ya.

I’ll tear yer guts out, silly old sow.

Sydney Morning Herald 18 January 1850 Ellen Welch… appeared before the Court, dressed in the latest fashion, her face was encircled with artificial flowers of the most choice selection, and her general appearance was certainly not that of a servant…

Sydney Morning Herald 19 December 1849 Judy Caerney…appeared before their Worships…charged with refusing to do her work. The bench ordered the indentures to be cancelled and Judy to be returned to barracks. In an hour or two afterwards she was seen walking through the town smartly dressed, and apparently in good spirits at having received between two and three pounds balance in wages. There is not a doubt but that was more money than the girl ever possessed before…

It’s not hard to imagine how excited young workhouse famine orphans were, at receiving wages, having money in hand, money to spend on new clothes. And excited, too, by the gifts and attention of male admirers. Or the feeling of independence, they had rarely known. Their mistresses and masters may well have been concerned, even jealous of their charge. Such displays as those of Ellen and Judy could lead to disapproval, words exchanged, quick wit, cutting repartee, impudence, and absconding on the part of orphan servants. The young women also may have resented their ‘inferiority’ in the household, and having to work harder than they’d ever worked before.

Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser 23 January 1850 Yesterday, Mr James Quegan applied to the bench to cancel the indentures of Bridget Kearney…[who] had latterly become insolent to her mistress and had refused to obey her orders. Kearney also wished to leave her service. The bench cancelled the indentures.

Ties formed on the long sea journey to Australia could be incredibly strong. The orphans made new friends and crafted their own moral code, doing what was right by each other, even if it meant breaking the law.

Sydney Morning Herald 22 April 1850 Irish Orphan Girls.–One of these girls, in the service of a family no great distance from the Emigrant Barracks, committed a robbery on her mistress. The articles consisted of a variety of baby linen, which were not missed till after the girl had left her service, when suspicion falling upon her by her mistress, search was made among the girls in the Barracks, and the articles found in the boxes of two other girls. It was ascertained that the object of the girl committing the theft was, to supply the anticipated necessities of the two girls, whose early accouchement is expected.

For some who were finding their way in their new land, it would involve a loss of sexual innocence. {All this makes me realize how little I know about Irish attitudes to work, the depth and extent of religious belief, and female sexuality before the Famine. I’m fairly confident their sex lives were not as repressive or as puritanical as they became in post-Famine Ireland}.

Sydney Morning Herald 19 September 1850. Page three provides an account of a case against Captain Morphew of the Tippoo Saib for a breach of the Hired Servants Act, he having harboured Julia Daly, a runaway from the service of A. H. M. McCulloch, an Elizabeth Street solicitor. Early in August Mr McCulloch had hired two orphans, Julia Daly and Mary Connor. By the end of the month they had absconded and gone to a hotel. Mary acted as witness in the case, stating “…they went to a furnished house at Newtown: there were two bedrooms in the house, one of which was occupied by her and the other by Julia and the Captain…she left Mr McCulloch’s because Julia would not stay, and she would go any where with her rather than stop alone… Other witnesses, including the owner of the house in Newtown, stated that Captain Morphew “represented Julia Daly as his wife”. Morphew was convicted, and fined £20, with costs.

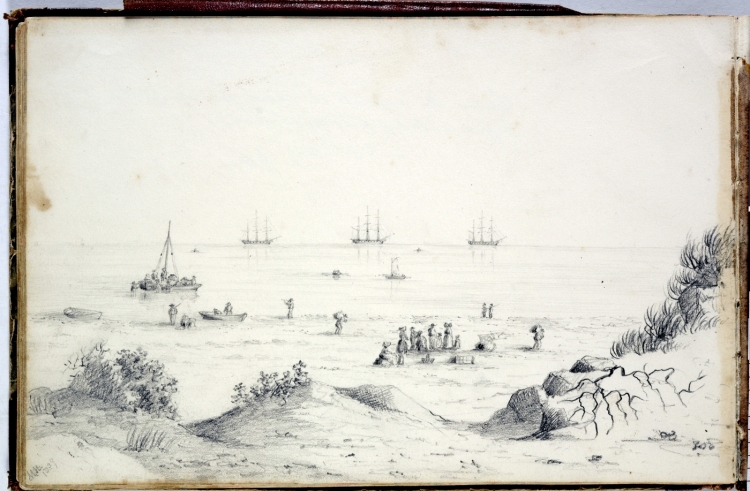

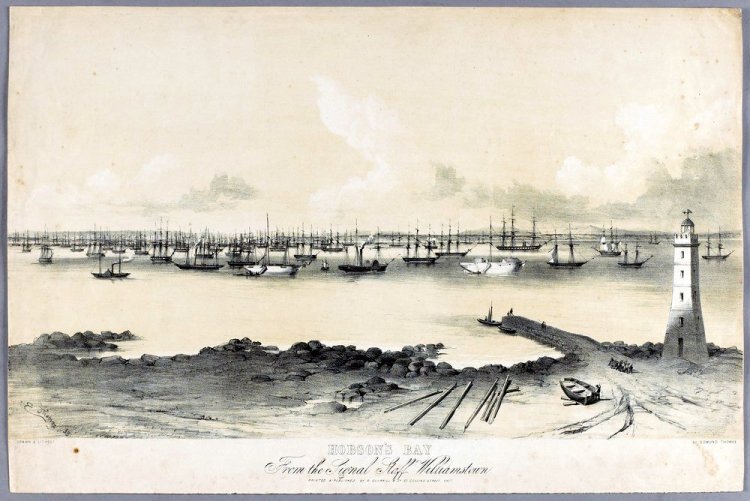

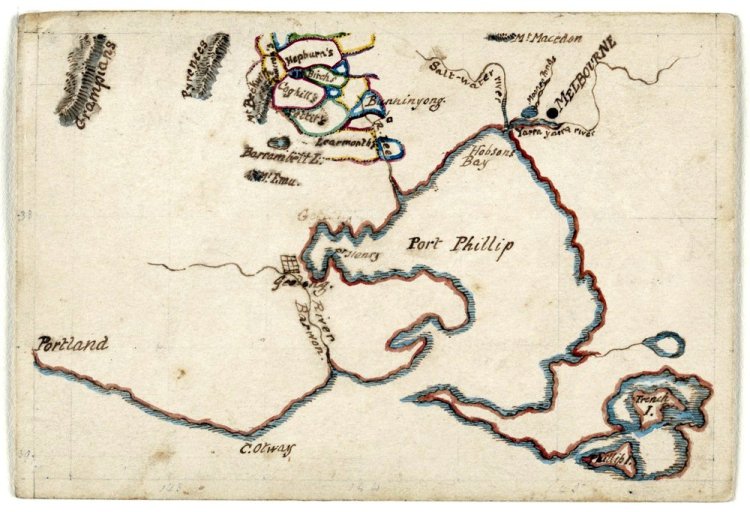

No doubt an orphan’s experience would differ from place to place, Sydney Town, the Port Phillip district, Geelong, the Victorian goldfields, Adelaide, country South Australia, and we’d need to examine that sometime in the future. Let me look at one in particular, for the moment.

The Moreton Bay District: orphans in court

One of the most interesting aspects of this whole saga of cancelled indentures is the freedom and skill with which orphans in the Moreton Bay district used the law to defend themselves and to ‘contest the hostile environment they found themselves in’. The history of the orphans’ cancelled indentures is a lot more complicated than Immigration Agent Browne would have us believe.

Some details of the story are in my Barefoot 2, Section 5 ‘Feisty Moreton Bay Women’, pp.112-23. Maybe your library has a copy? I didn’t learn about the court appearances of these young women, most of them from Clare, Galway and Kerry, until Libby Connors’s brilliant conference paper, at the 7th Irish-Australian Studies conference, in the University of Queensland, in 1993.

Assoc. Professor Connors examined the cases concerning orphans and the cancellation of their indentures that came before the Brisbane Court of Petty Sessions, in 1850 and 1851. Sometimes orphan apprentices initiated prosecution of their employer. Sometimes an employer was the plaintiff. The orphans, Professor Connors argued, were willing to assert their ‘legal rights and privileges’ and to contest ‘wage and employment issues’. Even as defendants, they ‘readily resorted to counter-claims of religious or ethnic discrimination and moral impropriety in the face of strong evidence of their own misbehaviour’.

Thus, for example, 2 August 1850, when Mary Byrnes from Galway complained to the court about her employer using “improper expressions“, she was awarded the wages owing to her; she had her indentures cancelled; and court costs were shared equally.

Likewise, 22 October 1850, Mr Windell, the master of feisty young apprentice, Margaret Stack from Clare, found her more than a redoubtable opponent in court. Windell presented evidence of Margaret’s persistent impudence and neglect of duty. She has for some time conducted herself in a most insolent manner…when sent to the butcher’s for meat, she took off her muddy shoes, and placed them in the basket, on the meat, which was consequently covered with filth; and when remonstrated with, and asked if she did not know better, she replied, NO I Do Not! He beat me and boxed my ears–many times.

A master did have a legal right to beat his apprentice, Dr Connors explains, but the Brisbane authorities, given the controversy surrounding the orphans, could not afford ‘any allegation of impropriety’. Margaret’s indentures were cancelled and she lost the 8 shillings in wages owing to her. But when an orphan had her indentures cancelled, she oftentimes considered herself to be the victor.

Margaret Smith Ni Stack and family

Margaret Smith Ni Stack and family msmith

msmithIn 1851, when Thomas Hennessy complained of the absenteeism and misconduct of young Mary Moriarty from Kerry, Mary countered with allegations of sexual harassment and beatings. Hennessy used to come to the sofa every morning and make uses of expressions I cannot repeat and because I laughed he struck me and kicked me down. Mary’s indentures were cancelled and she received the £1.2s.8d wages owed to her. For more information see Kay Caball, The Kerry Girls. Unfortunately we do not have the accent, or the intonation, of the young women recorded. Perhaps you would like to add that yourself? (See below for details of the origins of these particular young women).

Catherine Elliott Ni Moriarty and her family. Catherine was Mary’s sister.

Catherine Elliott Ni Moriarty and her family. Catherine was Mary’s sister.Whether the Moreton Bay District was unique or whether the orphans were as feisty and combative elsewhere, has yet to be discovered. There were, however, exceptional Moreton Bay circumstances we need to acknowledge. Setting aside the spirit and determination of the young women themselves, Dr Connors alerts us to a bureaucratic loophole that allowed them some freedom of movement. Because there was no Orphan Committee in Brisbane, she says, all orphan master-servant, master-apprentice contracts were sent to Sydney for approval, a delay the orphans were not slow to exploit. “They found themselves without legal restraint and took the opportunity to go from one job to another, residing at the barracks in between” (Connors, ‘Politics of ethnicity’, Papers delivered, 177).

It was an intolerable situation that should not be permitted, according to the Moreton Bay Courier, 25 August 1849 p. 2 column 4, http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/page/541372?zoomLevel=1

When one of those immigrants is engaged as an apprentice, the indentures are prepared in triplicate, signed by the employer, and transmitted, by the local Immigration Agent, to Sydney, for completion by the signatures of the guardians there. In the meantime, the servant is taken home by her master or mistress, who is not long in discovering that the young lady has full consciousness of her freedom from any restraint to bind her to her service. She will work if she pleases, but, if not,she returns to her idle quarters kn the barrack, and by the time that the indentures are signed and returned from Sydney the apprentice” is perhaps making trial of another service, to be vacated afterwards in a similar manner. This is clearly an evil that calls for remedy…we cannot recognise their claim to greater immunities, and it is certain that in ordinary cases, an apprentice would not be permitted to exercise the wilfully independent spirit which has been evinced in some instances by these Government “Orphans”. During the past week we have heard of a case where one of these gentle dames left her service for the avowed reason that she “would not eat the brad of a heretic”, and this is not a bad sample of some of the excuses given by others”.

Hurrah for the young women’s ‘wilfully independent spirit‘ that occasionally tipped the scales in their favour is all I can say.

Another ‘exceptional circumstance’ working in the young women’s favour was the ‘village’ scale of Brisbane. People knew each other, and each other’s business. The orphans met regularly and gave each other support. The Courier even reported the local Catholic priest, the Reverend Father Hanly, having a quiet word with the Bench, in favour of the feisty young Margaret Stack.

And if I may add something more…here are the orphans who appeared before the courts in Brisbane over breaches of Master-Servant legislation. What strikes you?

Mary Byrnes 15 year old from Ballynakill, County Galway per Thomas Arbuthnot

Catherine Dempsey 17 year old from Castlehackett, County Galway per Panama

Margaret Stack 14 year old from Ennistymon, County Clare per Thomas Arbuthnot

Catherine King 14 year old from Loughrea, County Galway, per Thomas Arbuthnot

Alice Gavin 16 year old from Ennis, County Clare per Thomas Arbuthnot

Mary Moriarty 16 year old from Dingle, County Kerry per Thomas Arbuthnot

Mary Connolly 14 year old from Kilmaley, County Clare per Thomas Arbuthnot

Jane Sharp 15 year old from Cavan per Digby

Apart from their tender years, and their origin in the West of Ireland, what struck me most is the name of the vessel they sailed in, viz. the Thomas Arbuthnot. If we could hear these orphans talk, what might they say? Perhaps “Thankyou Surgeon Strutt. God Bless you. You treated us with kindness and compassion. You believed in us and you made us believe in ourselves. You told us we, too, had rights, and we should stand up for ourselves”. (Every teacher knows that praise and positive encouragement are the best skills they can have).

MARRIAGE

Finally, the single most important reason for ending an orphan’s indenture was her marriage. Remember Frances Tiernan’s, “I’m going to get married and be my own mistress”. For marriage, permission from Orphan Committees had to be sought, and if the proposed spouse was a ticket-of-leave holder, from the Superintendent of Convicts as well. But this was usually granted: once the orphan married she was no longer the legal responsibility of her Guardians. I suspect most of the older ones did not bother seeking permission. From my family reconstitutions, an Earl Grey orphan married when she was just over nineteen years of age, and within two and a half to three years of her arrival. There are examples of my family reconstitutions in earlier posts. See, for example, http://wp.me/p4SlVj-gb [It follows that ‘orphans’ marrying’ is where I should go for the next post. Maybe I’ll do it later. I would like to take a closer look at the 1858 NSW Government enquiry first. Who knows]?

The marriage lottery; the sad case of Mary Coghlan

Allow me to finish by drawing attention to how much of a lottery an orphan’s marriage could be. The Moriarty sisters mentioned above, married well, and raised large families. Their story is told in Kay Caball’s lovely book, The Kerry Girls.

On the other hand, the ‘lottery’ was a disaster for Mary Coghlan from Skibbereen. I wonder if the Skibbereen orphans, badly traumatised by their experience of the Famine, found it harder than others to settle in Australia. Mary was a 17 year old when she arrived in Port Phillip on board the Eliza Caroline in 1850. With a number of shipmates–Mary Driscoll, Ellen Collins, Mary Donovan, Julia Dorney–also from Skibbereen, she was sent round the Bay to Geelong, where she was to meet her husband, James Walton. The pair quickly took off for the gold diggings at Ballarat. We know that Mary, returned to Geelong to baptise her first two children, Mary and James, in the St Mary’s of Angels Church.

It wasn’t till 1857 that we hear of them again, when both of them were on trial for the murder of Edward Howell in Ballarat. The report of the case in the Miner and Weekly Star, 1 May 1857, shows that alcohol played a part. Mary claimed Howell had called her a whore which provoked her to hit him on the forehead with a wooden batten. But what killed Howell, was not that blow but the head-kicking he received from James. A witness spoke in favour of Mary, The male prisoner [James Walton] was under the influence of liquor but he understood what he was about. I know the prisoner [Mary Walton] to be a hard working woman, and at the time the occurrence took place her husband was bound over to keep the peace towards his wife. At the end of the trial, after Mary was acquitted, the Judge, Mr Justice Molesworth, turned to Mary’s husband, James Walton, You appear to be a man addicted to liquor and using violence to your wife, and that violence perhaps led to her violence to the deceased. This, your violence has resulted in the melancholy loss of the life of a human creature. The jury with one exception, have recommended you to mercy, and I shall pass a more lenient sentence than I otherwise should do. The sentence of the Court is that you be kept to hard labor on the road for eighteen months.

Once again it is the Miner and Weekly Star 4 April 1862 that provides details of what happened. Luckily a more accessible copy of the report from the inquest is available in The Star Ballarat, 31 March 1862, Supplement, page 1, under the headline “Brutal Outrage in South Street”. You can view it at http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/page/6455284?zoomLevel=1 You will need to zoom in closer.

The inquest tells us more about what happened to Mary. Evidently, she suffered badly from domestic abuse. Her husband beat her physically and cruelly abused her psychologically. In mid March 1862, she was about a month short of full term when her husband assaulted her. After being thrown out of their tent into the cold, at night, from 7 p.m. till the early hours of the next morning, semi-clad, and having been “shoved and kicked about” by James, Mary lost yet another of her babies. Mary claimed he had made her lose four others by ill-treating her the same way. Before she died Mary made a deposition to the Police Magistrate in Ballarat, Stephen Clissold …He pulled me out of bed and shoved me one way and then another. I was stupid and taken in labor after he beat me, and I can’t tell half what he did to me… The child was born dead. Prisoner struck me with his hand and his foot. He struck me all over. He struck me with the point of his foot. I was tumbling on the floor. My daughter was in the house when he beat me. He ill-used me from the Saturday till the Friday, when the child was born. Sometimes he’d up and give me a shove or a slap.

Jane Skilling, a neighbour, deposed …While I was undressing, I heard her repeatedly asking to be let in. He refused, and she was still outside at two o’clock, when I had retired to my tent and fallen asleep. While sitting on the children’s bed, she told him that he had killed four children to her, and that he was trying to kill the fifth…The witness said that their 11 year old daughter had seen her father beat her mother on several occasions.

Margaret Mickison, another neighbour, deposed…During the nine months they have resided near us, the woman was a hard working woman, especially when her husband was in prison. While he was in prison I have once seen her intoxicated. She seemed to have taken drink at other times, but did her work. They were decent-like for a fortnight after he came out of gaol. She was never actually drunk, and kept her children very respectable during the time her husband was in prison. She was always working hard, and went out to wash.

After a brief period…the jury returned the following verdict:- “Her death took place…in the Ballarat District Hospital, and was caused by typhoid fever and enteritis brought on by a miscarriage, and such was occasioned by the ill-treatment of her husband, James Walton”. The prisoner was then removed to prison on the charge of manslaughter.

Poor Mary Coghlan, a victim of the Famine in Skibbereen. Indentures cancelled. Brutalized in Ballarat. Life ended.

And death shall have no dominion

no more gulls cry at their ears

or waves break loud on the seashores; (Dylan Thomas)

Post script.

As always, my thanks to family historians who provided me with documents and photographs.

Thanks also to Judith Kempthorne who did brilliant work as my research assistant (in late 1987 was it, whilst still an undergraduate?) working professionally through newspaper microfilm uncovering references to ‘Irish orphans’. Thanks heaps Judith.

Finally, a link to a post that lists the contents of this blog. I hope it will help us navigate our way around it.

For information about the annual gathering at Hyde Park Barracks and other events, see www.irishfaminememorial.org

You must be logged in to post a comment.