From County Westmeath, Ireland to County of Westmoreland, New South Wales.

By Caroline Thornthwaite

This is the story, as much of it as I have been able to put together, of Elizabeth Feeney, a young Irish Catholic orphan who migrated to the Australian colonies under the sponsorship of Earl Grey’s Famine Orphan Emigration Scheme. She is identified as passenger 97 on the Tippoo Saib, which arrived in Port Jackson on 29 July 1850.

Elizabeth, the daughter of Edward Feeny and Jane Thompson, was baptized on 27 June 1832 in the Townland of Mayne (Irish: Maighean), County Westmeath, Ireland.

The Civil Parish of Mayne comprises 19 townlands, including the townland of Mayne. The only village in the Civil Parish of Mayne is Coole, which lies in the townland of Coole (formerly Faughalstown) and borders the townland of Mayne. Geographically, Mayne Townland consists mainly of farming land and low-lying bog land. Its Irish name Maighean literally means ‘farmstead’.

The Catholic Parish of Mayne lies within the Civil Parish of Mayne in the Barony of Fore, County Westmeath. Civil registration of baptisms, marriages and deaths in Ireland did not begin until 1 January 1864. Prior to that, such records were often kept only by the conscientious priests, as they were under no legal or ecclesiastical obligation to do so. Fortunately, the parish priests of Mayne were of the conscientious type, and they kept records from the latter part of 1777. Sadly for family historians, some of the text has faded beyond reading and quite a few pages are missing from the record books.

The names Feeny and Feeney occur in the surviving Church records only on about a dozen occasions, and only between the years 1815 to 1864. This suggests that the family probably moved into the district not long before 1815. There are no Feenys mentioned in the Church records of neighbouring townlands. There are no notations in the church records to indicate where the Feenys came from or what brought them to Mayne Townland. They may, however, have had relatives in the Parish as there are several instances found in church records connecting them to the Tormey family.

There is no record of any Feenys in the Tithe Applotment Books for the Parish of Mayne. These books were compiled between 1823 and 1837 in order to determine the amount which occupiers of agricultural holdings over one acre should pay in tithes (a 10 per cent religious tax) for the upkeep of the Church of Ireland. Their absence from the Tithe Applotment Books suggests the family were probably farm labourers. If the family had leased any land during those years, it would likely only have been a small plot for growing potatos: potatoes and milk having been the staple diet of the agricultural labouring population until the great famine which decimated the population in the mid-1800s.

Only one Feeny is listed in the Griffith’s Valuation of Ireland for the Parish of Mayne. This valuation of tenements was compiled between 1847-1864 and was a uniform guide to the relative value of land throughout the whole of Ireland. It was used to calculate the amount of Poor Rate each occupier of land was liable to pay. The Poor Rate was effectively a tax for the support of the poor and destitute within each Poor Law Union.

The Valuation of Tenements printed in 1854 lists a James Feeny who rented a house, forge and garden from Reverend Thomas Smith in the Parish of Mayne, Village of Upper Coole, Westmeath. Church records show that James died in 1864. The record gives no indication of his age, marital or social status but simply states “1864, February, Jas Feeney, Coole”. At that time Coole was in the townland of Faughalstown (it later became the townland of Coole) and was also part of the Parish of Mayne.

Given the scarcity of Feenys in the church and civil records and, considering the timeline of the records found so far, it would seem safe to make some assumptions about the make-up of the family.

The family patriarch was Richard, who died in May 1820; age not given. Richard’s wife was Anne; maiden name not given. Anne, described as a widow, died in July 1837; age not given. According to the records, both Richard and Anne were parishioners of the local Catholic church and residents of Mayne Townland. Richard and Anne seemed to have had one daughter and three, possibly four, sons.

A son, Edward, first appears in the records as Edward Finey, a sponsor at the baptism of James Tormey in January 1815. According to Catholic Canon Law, a godparent had to be at least 16 years of age, therefore, Edward could not have been born any later than January 1799.

On 6 February 1829, a daughter, Elizabeth Feeney, married Laurence McGrath. The witnesses were John Reilly and Mary Tormey. Their daughters, Mary and Anne, were baptized on 4 October 1829 and 7 October 1829 respectively; no dates of birth given. Mary’s godparents were Francis Gordon and Mary Tormey, and Anne’s godparents were Terence Clarke and Mary Tims.

On 16 February 1829, Edward Feeney married Jane Thompson in Mayne on 16 February 1829 in the presence of the Reverend Francis Sheridan and the Reverend John Leavy. Jane Thompson was a recent convert to the Catholic faith. She made her profession of faith, and was received into the Roman Catholic church, on 2 November 1828 in the presence of Francis Gordon and James Hughes.

In April 1836, the records show a death for a Mary Feeney, married, from the Parish of Mayne, residing in Mayne Townland: no maiden name given. In April 1843 they show a death for an Elenor Feeny, married, from the Parish of Mayne, residing in Mayne Townland; no maiden name given. Presumably both Mary and Elenor had married one of Richard and Anne’s sons. Perhaps one of them had been the wife of James.

Tragedy struck Edward and Jane’s daughter Elizabeth very early in her life. Edward died on 17 July 1832, a mere 20 days after his daughter Elizabeth was baptized. No details apart from the date of Edwards death were recorded. While still in her teenage years, a second tragedy struck young Elizabeth’s life. The Great Hunger of 1845-1852 had a significant effect on the population of Mayne Townland, an area of 541 acres (about 219 hectares). According to the 1881 Census of Ireland (Province of Leinster), before the famine the population in 1841 was 193 people living in 31 dwellings. Towards the end of the famine in 1851, the population was 118 people living in 20 dwellings. Over the next ten years the population continued to fall and by 1861 there were only 56 people living in 12 dwellings.

While still a teenager, Elizabeth Feeney experienced the horror of starvation, the degradation of homelessness and the grief of family loss; a trifecta of tragedy which was suffered by so many Irish during the Great Hunger. As a last refuge from starvation, perhaps with her mother, or other extended family members if any were still alive, Elizabeth sought the shelter of the Granard Workhouse in nearby County Longford. The Granard Workhouse covered an area of 217 square miles (about 532 square kilometres). Its catchment included 15 electoral divisions over 3 counties, including the Electoral Division of Coole, of which Mayne Townland belonged. It is not possible to confirm whether Elizabeth’s mother Jane or any other family members entered the workhouse with Elizabeth, as there are no surviving Poor Law Union records for the Granard workhouse for the famine years of 1848 – 1851.

Just short of one year after her arrival in New South Wales, Elizabeth married Samuel Slater, a former convict who had, having received a life sentence for housebreaking, received a conditional pardon two years earlier. That Elizabeth Feeney, wife of Samuel Slater, is the same person as Elizabeth Feeny, orphan immigrant, is beyond doubt. The only immigration record found in the archives of the State Records Authority of New South Wales that could possibly match Elizabeth’s arrival in the colony of NSW is found in the Assisted Immigrants Index, in the passenger records for the Tippoo Saib, which arrived in Port Jackson on 29 July, 1850.

According to NSW immigration records and Elizabeth’s death record, her year of birth is calculated as 1835; according to her baptism record and marriage record it is calculated as 1832. Her 1901 obituary[1] states Elizabeth was 69 years old when she died and had lived in the Goulburn district for more than 50 years. That would place her approximate year of birth as 1832 and her arrival in the colony before 1851. The original record of the Tippoo Saib ship passenger manifest shows:

No. 97 Feeny Elizabeth, age 15, Dairymaid, Native of Mahan Westmeath, Church of Rome, neither read nor write[2].

The Immigration Board passenger inspection list, recorded before the passengers were permitted to disembark, corroborates the data on the ship passenger manifest and describes Elizabeth’s “state of bodily health, strength and probable usefulness” as “good”.

No. 97 Feeny Elizabeth, 15, Dairymaid, Mahan W. Meath, parents Edward & Jane both dead, Roman Catholic, neither read nor write, no relations in the Colony[3].

The age discrepancy on her immigration documents may have been a clerical error, or Elizabeth may have lied about her age, particularly if the workhouse Board of Governors favoured selecting younger females for the orphan emigration scheme (her year of birth is calculated as either 1832 or 1835 on all the official records discovered thus far). A further possibility is that Elizabeth may not have known how old she actually was.

Elizabeth’s place of residence in Ireland is given as Mahan in County Westmeath, however, there is no Mahan found on contemporary maps of County Westmeath or mentioned in Griffiths Valuation of Tenements 1848-1864. Possible locations for Elizabeth’s place of residence in Ireland were Mahonstown, about 12km east of Mullingar, and the townland of Mayne (Irish: Maighean), located about 18km north of Mullingar. A search of the County Westmeath Catholic Church records was rewarded by the find of an Elizabeth Feeny, daughter of Edward and Jane, baptized in the Townland of Mayne in 1832. It is likely that Mahan was a phonetic spelling as heard by the ear of the record-taker.

Elizabeth fared better than many of her orphan contemporaries. Because she was a dairy maid, it is likely that her time at the Hyde Park Barracks would have been short; girls with her experience would have been sent directly to a farming area rather than be sent out as domestic servants. From what we know of Elizabeth’s life, it seems that she was transferred from Hyde Park Barracks to the Immigration Depot at Goulburn, probably enduring a long and uncomfortable journey over the Great Dividing Range by bullock dray. From Goulburn, she would have been collected by her new employer and settled into her new life in the farming community at Richlands, about 45 km (28 miles) north of Goulburn. At that time the Richlands estate, including the estate workers’ village now called Taralga, was owned by William Macarthur and managed by his brother James, sons of the infamous John Macarthur – racketeer, entrepreneur, instigator of the Rum Rebellion and pioneer of the Australian merino wool industry. The Series NRS-5240 Registers and indexes of applications for orphans 1848-1851 held by the State Records Authority of NSW archives holds no details specific to Elizabeth Feeney, nor is there mention of indentures for any of the orphans who arrived aboard the Tippoo Saib in July 1850. The index for 1850 does, however, mention correspondence from the colonial Immigration Agent dated 21 March 1850 forwarding a letter from WJ McArthur of Goulburn “enclosing five Indentures completed and six for completion”. Further correspondence is mentioned in July 1850 from the Immigration Agent forwarding a letter from J McArthur Esq., Goulburn, “reporting the marriage of Mary Lanahan (sic) and Mary Leery (sic), Orphan Females per William & Mary”[4]. The J McArthur referred to was probably JF

[1] http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article104423164, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article100407211

[2] http://indexes.records.nsw.gov.au/ebook/list.aspx?series=NRS5316&item=4_4786&ship=Tippoo%20Saib.

[3] State Records Authority of New South Wales: Shipping Master’s Office; Passengers Arriving 1826 – 1900; Part Colonial Secretary series covering 1845 – 1853, reels 1272 [4/5227], 1280 [4/5244].

[4] The orphan ship William & Mary arrived in Sydney on 21 November 1849. Mary Lenahan was employed by William King of Goulburn at £8 for a period of 12 months. Mary Seery was employed by Thomas Capel, a brewer from Goulburn at £10 for a 12-month period. Mary, as Mary Saary, married John Steward on 1 July 1850 at St Saviour’s Church of England, Goulburn.

McArthur Esq, a Justice of the Peace and a sitting Magistrate on the Goulburn Bench. He, presumably, was acting on instructions from the Immigration Office in Sydney in the role of a local guardian.

Although the name of Elizabeth’s employer is not known, such correspondence confirms that young women from the Orphan Emigration Scheme had been sent to employers in Goulburn from at least 1849 onwards, as three orphans from the William & Mary are known to have been in Goulburn in early 1850[1].

Of the 297 orphan girls on board the Tippoo Saib, Elizabeth was one of only seven dairy maids, the other girls being mainly general house servants or nurse maids. Elizabeth may have been selected for employment specifically for that reason and employed either by Messrs Macarthur or one of their Richlands tenants, some of whom were dairy farmers[2]. Various birth, death and marriage records confirm that Elizabeth lived on the Richlands estate for the remainder of her life.

On 25 June 1851, one year after her arrival in New South Wales, Elizabeth married Samuel Slater at Richlands homestead, the home of the estate manager, Mr George Martyr. The marriage was conducted by William Sowerby, a minister from St Saviour’s Church of England, Goulburn. Samuel Slater had been assigned to James Macarthur in 1832 and worked between the Macarthur-owned estates of Camden Park and Richlands. On being granted a Ticket of Leave in 1841, Samuel was employed by the Macarthur family and soon relocated permanently to Richlands around 1842. Samuel received a Conditional Pardon in 1848.

At the time of Elizabeth’s arrival in the district, there were about 50 families living on the Richlands estate. They were all tenant farmers growing cereal crops such as wheat, oats and barley, or raising sheep, cattle, pigs and horses. The usual lease arrangements were 20-year leases for £15 per acre. Most of the lots averaged about 500 acres in size and were on what was widely considered to be some of the best land in the colony.

The marriage record of Samuel Slater and Elizabeth Feeney states that the groom was a bachelor, born in Derbyshire, a Stonemason, age 58 [according to the government records Samuel would actually have been 48], residing at Richlands, parents not listed. The bride was a spinster, born in Ireland, occupation not listed, age 19, residing at Richlands, parents not listed. The witnesses were George Martyr (the manager of Richlands estate), Angus Mackay (who would later become Instructor in Agriculture to the Board of Technical Education) and Elizabeth Weeks (wife of one of the tenant farmers), all of Richlands. The couple were married by banns. The bride signed with her mark[3].

The marriage of a 19-year-old girl to a man nearing his 50th birthday would be almost unheard of in our day and age, but at that time marriages were nearly always a matter of convenience. If love were to flower in time, all the better. In the case of Elizabeth and Samuel, the marriage would have been mutually beneficial. In marrying Samuel, Elizabeth would be working for herself and her future family; she need never be at the beck and call of an employer again. On the financial side, Samuel had been a wage-earner for almost ten years and, if he was not already a leaseholder, was probably well on his way to affording to lease his own farm on the Richlands estate. In marrying Elizabeth, Samuel had gained a young and healthy wife; as a dairymaid, Elizabeth knew her way around cattle and would contribute to the work of a farm, as well as provide Samuel with the creature comforts of home and companionship.

[1] In addition to Mary Lenehan and Mary Seery, Mary Ann Long (according to the Famine Orphan Database) on “14 Feb 1850 one of 4 orphans who absconded from Mr Peter’s dray on way to Wagga, returned to Goulburn Depot.”

[2] Dairy products had been produced since the earliest days of settlement in the Taralga district. The 600-acre property granted to Mr Thomas Howe, cheesemaker, in 1828 was later purchased by Edward Macarthur as it joined the northern boundary of Macarthur’s ‘Richlands’ estate. Richlands homestead and its various buildings were subsequently built there. Source: Taralga Historical Society Inc, 83 Orchard Road Taralga, NSW, 2580, Newsletter No 4, 2019, http://taralgahistoricalsociety.com.au/THS%20NEWS%204,%202019.pdf.

[3] NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages, Marriage 434/1851 V1851434 37B, Slater Samuel, Feaney Elizabeth, MC.

A later map of the Richlands estate shows that the Slaters were indeed tenant farmers on the estate. Their farm was close to Stonequarry Road on part of Portion 3, Guineacor Parish, County of Westmoreland. Just past the Stonequarry Cemetery is a sharp bend in the road that was known as Slater’s Corner[1]. It can be accessed from an unnamed road off what is now Golspie Road via Taralga.

Elizabeth and Samuel were married for 18 years and had thirteen children together. Sadly, only seven of their children survived to adulthood. According to Samuel’s death certificate of 1869, two males and three females died in infancy (those births were not registered, which was not uncommon in the remoter areas of the colony) and toddler Samuel Junior, not yet two years old, fell into a well and drowned. Of the remaining seven children, four males and three females, all but Joseph married and had children of their own. The older children seem to have been baptized into the Anglican faith and the younger ones into the Roman Catholic faith. This may have been due to a lack of Catholic clergy in the area in the earlier years, as the first Catholic church built in the area was St Ignatius at Taralga in 1864, and even then, the priest was attached to the parish at Crookwell, 39 km (29 miles) away.

The four surviving adult sons – Thomas, Samuel Francis, Edward and Joseph – initially all lived in the Taralga area on or near the Macarthur Richlands and Guineacor properties; first as labourers, then later as tenant crop farmers and also raising horses, cattle and sheep. The Slater brothers’ personal stock brands were registered and published in the NSW Government Gazette between 1890 and 1921. Thomas, who “was of a retiring disposition” and “well-liked by all who knew him”[2], married Norah Foran, a farmer’s daughter and assisted immigrant from Glasclune, County Clare, Ireland who had arrived in 1881 per Clyde. Thomas and Norah eventually pioneered at Redground, to the northeast of Goulburn. Of Thomas and Norah’s children, three daughters and one son married siblings from the neighbouring Skelly family, whose parents were both of Irish descent. Thomas died at Goulburn in 1939. Joseph remained a bachelor and died at the Rydalmere Mental Hospital in 1944. Samuel Francis, a “widely known stockman”[3] and who was “well known and highly respected throughout the community”[4], married Norah Foran’s younger sister, Catherine. Catherine (known as Katie or Kate) was also an assisted immigrant, arriving in 1886 per Port Victor. Sam and Kate bought a 200-acre grazing property at Wombeyan Caves to the northeast of Taralga in 1910, which they called Wattle Flat. Sam worked his property until shortly before his death at Goulburn in 1950. Edward married Mary Lennam, a nurse, also of Irish descent. He is believed to have died in Tasmania.

Of Sam and Elizabeth’s daughters, Mary Ann married Michael Barry from County Galway. He was a road maintenance worker who was “widely known and respected as an upright citizen whose kindly nature had endeared him to a wide circle of friends”[5]. Mary Ann died at Goulburn in 1930. Sarah (registered as Lydia but known as Sarah or Sadie) married Englishman Edward Searle. After starting their family at Taralga, they lived on Lord Howe Island for a time growing Kentia palms. From there, they lived for a short time at Captain’s Flat before pioneering in the Macleay District, where they established a prosperous farming property out of virgin scrubland. Sarah died at Macksville in 1942. Elizabeth Anne married David John McAleer, the son of an Irish immigrant. McAleer was a stockman to the Macarthur-Onslow family at the Richlands and Camden Park properties for many years. Elizabeth Anne managed the boarding house for workers at Camden Park for nine years. Miss Sibella Macarthur-Onslow sent a floral wreath when Elizabeth died in Camden in 1933[6]. The obituaries for all three daughters mention their kind dispositions; Mary Ann had “a wide circle of friends to whom she had endeared herself by her kind and charitable actions”[7], Sadie is praised for travelling “long distances on horseback on her errands of mercy”[8], while Elizabeth Anne’s “main pleasure in life was to help others”[9].

One can only imagine Elizabeth’s delight when three of her sons married Irish brides and two of her three daughters married Irish-born or Irish-descended men. Did they speak Gaelic and reminisce about the old country when they were together? Did they sing Irish folk songs and share stories around the fireplace? Perhaps it helped to ease any homesickness or sadness at separation from family, perhaps the Irish commonality strengthened the bond of extended family ties.

Samuel Slater died in 1869, leaving Elizabeth a widow at a relatively young age with seven minor children to care for, one of whom was just a babe in arms. Elizabeth did not remarry, as many of the other Earl Grey orphans were forced to do to ensure some kind of security for themselves and their children. According to Elizabeth’s 1901 newspaper obituary, many years earlier she had been granted a farm free of rent for her lifetime in consideration of the Slaters’ long and faithful years of service to the Macarthur family. That farm and house would have been the property on Portion 3, where the Slaters had been farming and raising stock for some years. This act of generosity was undoubtably at the hand of Mrs Elizabeth Macarthur-Onslow (James Macarthur’s sole child and heir) and would have occurred at the time of Samuel’s death. Mrs Macarthur-Onslow had a reputation as a kind and generous person who had great concern for her employees and their families and “was always devising ways to give them better homes and brighter lives”[10]. Elizabeth remained a widow for 31 years.

In January 1901, Elizabeth contracted influenza resulting in pneumonia. After a nine-day illness, she died in her home at Richlands on 14 January 1901, having been well cared for by her family and attended to by her parish priest. Her death certificate states she was 69 years old, born in County Westmeath, Ireland and that her time in the colony was 56 years[11]. Elizabeth’s son Edward was the informant; however, there are errors in the information he provided. Edward mistakenly attributed his own father’s trade of stonemason to Elizabeth’s father and gave the name of Elizabeth’s mother as Elizabeth instead of Jane. Although Elizabeth did not name any of her daughters after her own mother, three of her granddaughters were given Jane as a middle name (Elizabeth Jane Barry, Bessie Jane Slater and Clara Jane McAleer). It is likely that Elizabeth was, herself, generally referred to as Bessie. Elizabeth was buried on 16 January 1901 in the Catholic section of the Stonequarry Cemetery (now Taralga Cemetery), off Golspie Road near Taralga, NSW.

The day after Elizabeth’s funeral, her house and its entire contents burned to the ground due to an accidental fire. Elizabeth’s orphan box may well have been among the contents destroyed in the fire. That same little box, made to a regulation size of 2 feet long x 14 inches wide x 14 inches deep (61cm x 35.5cm x 35.5cm) and with her name painted on the front, that accompanied her to Australia and was full with treasure in the form of clothes and personal items, all brand new and of good quality in accordance with a list prescribed by the Emigration Commission which was pasted inside the lid.

Only one of the boxes issued to the 4,114 girls participating in the Orphan Emigration Scheme in NSW is known to have survived and was on display in the Hyde Park Barracks Museum in Macquarie Street, Sydney in 2021.

Box belonging to Margaret Hurley from Gort, Co. Galway per Thomas Arbuthnot (arrived Sydney 1849).

Owned by her great-granddaughter, Rose Marie Perry. Photo: Darrell Thornthwaite.

Elizabeth’s obituary was published in The Catholic Press and the Goulburn Herald.

The Catholic Press, 26 January 1901, p. 24. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article104423164

Headstone of Elizabeth Slater nee Feeney

and her husband Samuel Slater,

Stonequarry Cemetery, via Taralga, NSW.

The details given for Samuel are incorrect – he

died on 13 September 1869, aged 68 years.

Photo: Darrell Thornthwaite.

Elizabeth Feeney and Samuel Slater had at least 40 grandchildren. Their descendants include pioneering farmers, stockmen, graziers, votaries, health care professionals, public servants, servicemen in the armed forces and fire brigade, schoolteachers and businesspeople. Although there is little in the surviving records to tell us much about Elizabeth as a person, we can safely deduce that she was level-headed and not fearful of taking big steps to ensure her own survival against huge odds; that she was a dedicated wife and mother who knew the pain of losing some of her children at far too young an age; that, as a young widow, she was physically and emotionally strong enough to bring up her children alone; that her surviving children loved her and cared for her in her old age; that she had a most generous benefactress who deemed Elizabeth, even though she was not yet 40 years old, deserving of farmland and housing free of rent for the rest of her life; that she had brought up her children to be good, kind and charitable people who were well thought of by all who knew them; that she was a woman of faith; and that she was well respected within her community because her funeral was “very largely attended”. Elizabeth will be remembered by her descendants as one of the 4,114 Irish orphan females landed in NSW who truly became the ‘mothers of Australia’.

Researched and written by Caroline Thornthwaite, 2022.

For my husband Darrell and his three brothers, Dennis, David and Bruce; fourth-generation descendants of Samuel Slater and Elizabeth Feeney.

REFERENCES/ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Barclay, Barbara 2015, The Mayo Orphan Girls, viewed 2021, http://mayoorphangirls.weebly.com/orphan-emigration-scheme.html

Barclay, Barbara 2017, ‘It was like landing on the moon’: Finding the fate of Irish Famine orphans sent to Australia, viewed 2021,

https://www.thejournal.ie/mayo-orphan-girls-australia-3448701-Jun2017/

Fairall, Jonathon Relph 2019, Earl Grey’s Daughters: The women who changed Australia, SPSP Publishing, 2nd Ed.

Higginbotham, Peter, The Workhouse: The story of an institution: Granard County Longford, viewed 2022, https://www.workhouses.org.uk/Granard/

Irish Famine Memorial Sydney, Orphan Database, viewed 2021, https://irishfaminememorial.org/

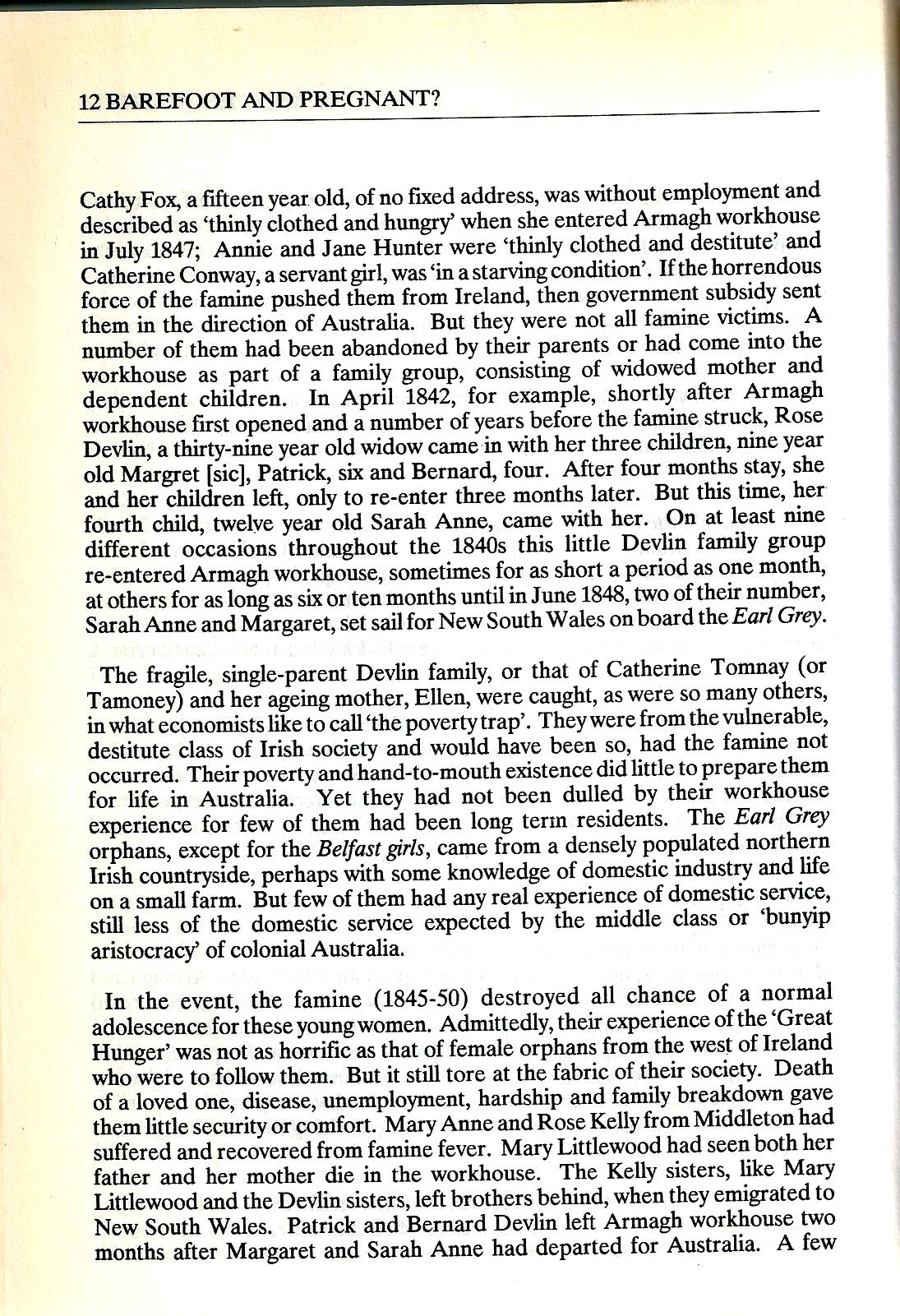

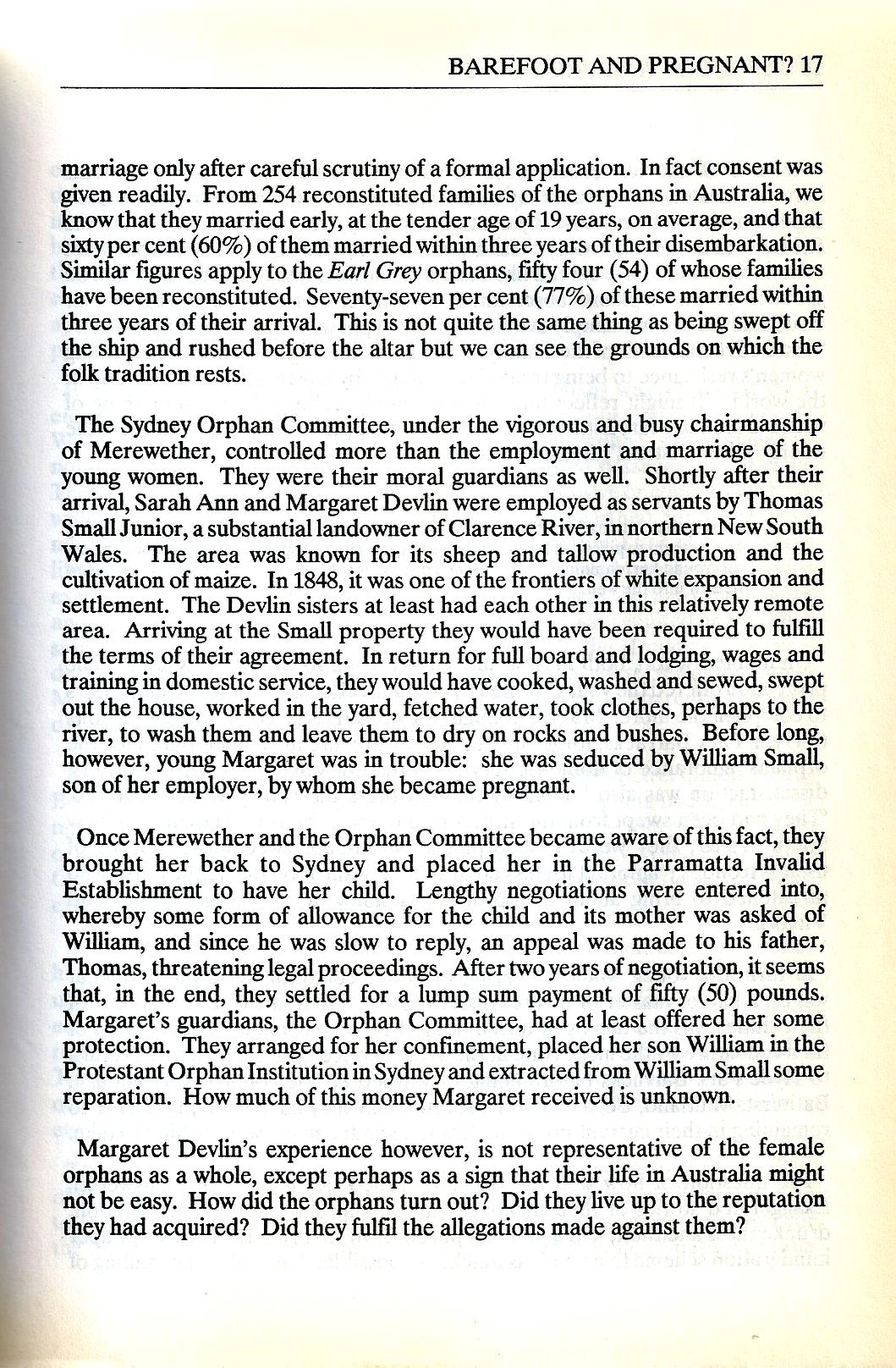

McClaughlin, Trevor 1991, Barefoot and Pregnant?: Irish Famine Orphans in Australia, The Genealogical Society of Victoria Inc. (e-book)

McClaughlin, Trevor 2000, “Lost Children?”, History Ireland, viewed 2021

McClaughlin, Trevor 2022, ‘Trevo’s Irish Famine Orphans, blog pages viewed from 2021 -2022, https://earlgreysfamineorphans.wordpress.com/author/trevo1/

National Library of Australia, Trove (online collection), viewed 2021-2022, https://trove.nla.gov.au

National Library of Ireland, Catholic Parish Registers at the NLI, Mayne, viewed 2021, https://registers.nli.ie/parishes/0919

Radio Teilifis Eireann, Girls of good character: female Workhouse emigration to Australia during the Famine (Perry McIntyre), viewed 2022, https://www.rte.ie/history/post-famine/2021/0202/1194606-good-character-female-workhouse-emigration-to-australia/

State Records Authority of NSW, Assisted Immigrants (digital) shipping lists 1828-1896, Tippoo Saib 29 July 1850, viewed 2021, https://indexes.records.nsw.gov.au/ebook/list.aspx?Page=NRS5316/4_4786/Tippoo%20Saib_29%20Jul%201850/4_478600555.jpg&No=6

State Records Authority of NSW, Immigration – Registers and Indexes of Applications for Orphans 1848-51, Item 4/4716, Register 1850-51, Volume 3, Reel 3111.

State Records Authority of New South Wales: Shipping Master’s Office; Passengers Arriving 1826 -1900; Part Colonial Secretary series covering 1845 – 1853, reels 1272 [4/5227], 1280 [4/5244].

Sydney Living Museums, Irish Orphan Girls at Hyde Park Barracks, viewed 2021

https://sydneylivingmuseums.com.au/stories/irish-orphan-girls-hyde-park-barracks

Taralga Historical Society Inc, 83 Orchard Road Taralga NSW 2580, conversations andcorrespondence with Mrs MaryChalker 2021, http://taralgahistoricalsociety.com.au

Williamson, Pat 2006, Guinecor to Bubalahla, Taralga Historical Society, Orchard Street Taralga NSW 2560

[1] Williamson, Pat (2006). Guinecor to Bubalahla, Taralga Historical Society, Orchard Street, Taralga NSW 2560, ISBN 0958024936, page 116.

[2] Goulburn Evening Penny Post, 1 September 1939, Obituary, Mr Thomas Slater.

[3] Crookwell Gazette, 18 January 1950, Obituary, Mr Samuel Slater.

[4] Goulburn Evening Post, 9 January 1950, Obituary, Mr Samuel Slater.

[5] Goulburn Evening Penny Post, Wednesday 30 November 1927, page 2, Mr Michael Barry.

[6] Camden News, Thursday 13 July 1933, page 1, Obituary, ELIZABETH AGNES McALEER.

[7] Goulburn Evening Penny Post, Tuesday 1 April 1930, page 2_Obituary, Mrs Mary Barry.

[8] Macleay Argus, Tuesday 9 June 1942, page 2, OBITUARY MRS SARAH SEARLE.

[9] Picton Post, Wednesday 12 July 1933, page 2, Elizabeth Agnes McAleer.

[10] 1911 ‘The Late Mrs. Macarthur Onslow.’, Camden News (NSW: 1895 – 1954), 10 August, p. 5., http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article136639794.

[11] NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages, Death 3217/1901, Slater Elizabeth, Taralga.

My thanks to Caroline Thornthwaite who has kindly allowed me to put into my blog, her well-researched and finely written orphan story, that of Elizabeth Feeney from ‘Mahan, Westmeath’ per Tippoo Saib. She hopes readers will find it either interesting or useful, or both.

Note the names of some of her married daughters, Margaret McGuire, Christiana McWhiney, Annie Tandevine(?), Cecilia Hockings, and Jessie Mercer.

Note the names of some of her married daughters, Margaret McGuire, Christiana McWhiney, Annie Tandevine(?), Cecilia Hockings, and Jessie Mercer.

You must be logged in to post a comment.