Most readers will know of the recent death of Tom Power a man who played such a crucial role in the creation of the monument to the Great Irish Famine at Hyde Park Barracks in Sydney http://www.irishfaminememorial.org/ This wonderfully evocative artwork was a commemoration and a memorial to all the Irish people who fled the Famine and came to Australia. Its symbolism gave it universal significance. It became a tribute to everyone fleeing famine and catastrophe anywhere in the world. Tom knew that public monuments die by neglect. His hope was that this one, ‘his’ one, would be a living monument, life breathed into it by the descendants of orphan girls memorialized on the glass panels in Hossein and Angela Valamanesh’s beautiful sculpture.

This can happen in a myriad of ways,

on an Irish Language television channel, TG4, with Barrie Dowdall and Siobhán Lynam’s TG4 series, “Mná Díbeartha/ Banished Women” http://www.convictwomenandorphangirls.com/Convict_Women/Home.html

in the creative imagination of an artist. Jaki McCarrick’s “Belfast Girls” will be shown for the first time to an Australian audience, later this year 2018, in the middle of May. http://htg.org.au/htg-presents-belfast-girls-an-australian-premiere/

in cyberspace with the Keeper of the Orphan database, the inimitable Perry McIntyre, http://irishfaminememorial.org/orphans/database/

There’s a host of other ways. Maybe readers would mention them in a comment to this blogpost?

In homage to Tom Power I’d like to present another brief ‘herstory’. It is based on information provided by a descendant, Alan Buttenshaw. Alan provided me with a file of information relating to Winifred Tiernan and her husband, David Masters when I met him in 2003.

My starting point for up-to-date information on the Earl Grey orphans is always www.irishfaminememorial.org/orphans/database

So for

WINIFRED TIERNAN/TIERNEY FROM ROSCOMMON per TIPPOO SAIB

there is the following,

- Surname : Tiernan (Tierney)

- First Name : Winifred

- Age on arrival : 16

- Native Place : Ardcarney [Ardcarn], Roscommon

- Parents : James & Margaret (both dead)

- Religion : Roman Catholic

- Ship name : Tippoo Saib (Sydney Jul 1850)

- Workhouse : Roscommon, Boyle

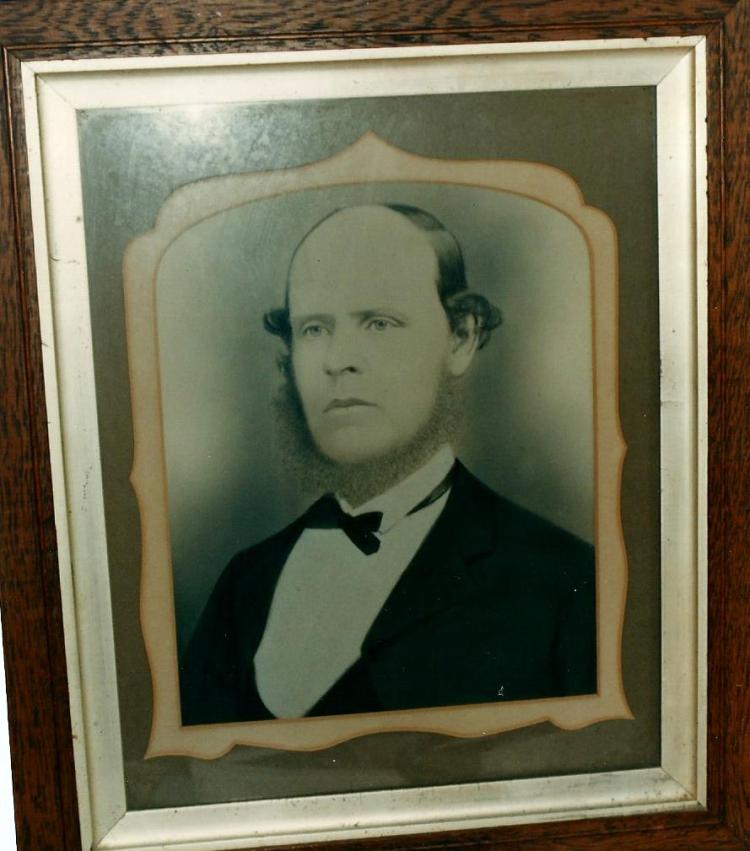

- Other : Shipping: house servant, reads, no relatives in colony. 1858-9 Report, appendix J No.150, 29 Nov 1850 indentures cancelled with Mr J Caruthers, South Head Rd, for insolence & neglect of duty, sent up the country, WPO; Im Cor 50/917, 16 Dec 1850 Maitland; mar David Masters 7 Jun 1853, St James, Morpeth; then to Mitchell’s Island nr Taree, farming husband’s property; 15 ch; she died 12 May 1909. Photo p.289 Barefoot & Pregnant, vol.2. Heather Peterson: cadie[at]ace-net.com.au; Alan Buttenshaw: abuttens[at]bigpond.com.au; Darlene McGrath, email bounced, please contact us

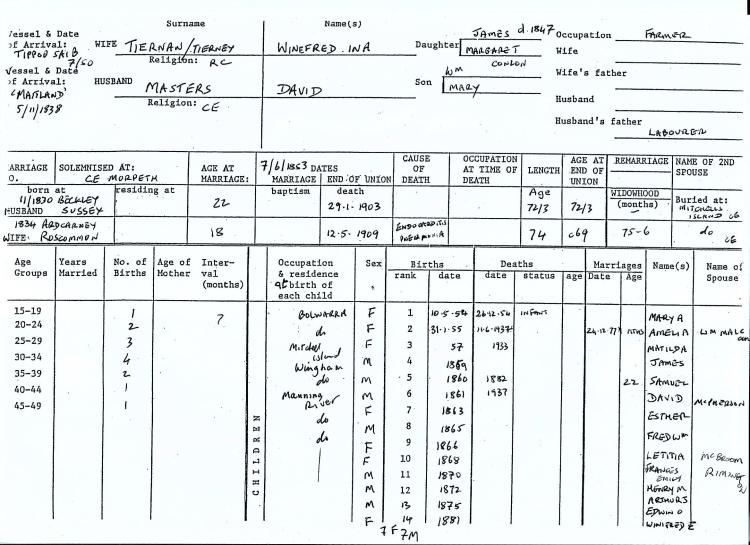

Further down this post you will see the family reconstitution form I constructed after meeting with Alan. Alas, I never developed her history as either of us had hoped. Here is a brief version of ‘herstory’ anyway. It may assist other family historians writing her story if they haven’t done so already. It appears there were fourteen, not fifteen children born to the couple. Both were residing in Bolwarra Parish at the time of their wedding in St James Anglican church in Morpeth in 1853. I can’t help noting how long a child-bearing life Winifred had.

Some of the information in Alan’s file had been passed to him by other family members, including the transcript of a tape by Winifred’s granddaughter. It was a tape recording what Winifred had told her granddaughter about the Famine and the death of her parents. According to this, Winifred’s mum, Margaret Conlon died in 1846, followed by her dad and brother James the year after, in 1847.

Let me quote from the transcript,

“At the end of 1846 Great Grandmother Margaret, took ill. Her husband tookCatherine [Winifred’s younger sister who came to Australia in 1856] and James with him and slept in the hayloft above the cowshed. Each morning he took the milk and whatever else could be found in the way of food and left it on the kitchen doorstep. But he never went inside the house. The mother died, the two girls laid her out. … At the end of 1847, this time the father and the son James were stricken. A cart came to pick up any dead, and a neighbour told the men to call on the way back. The father was already dead, and by the time they returned the son would be also. There weren’t any records kept of who had died they were all buried in a large hole. This left the three girls orphans, Mary 15 yrs, Winifred, 12 and Catherine 9″.

One of the fascinating things about the transcript is the way we humans construct our memories to suit ourselves. In the transcript there is no mention of Winifred ever having been a workhouse and no mention of her indentures being cancelled or being sent up the country to Maitland.

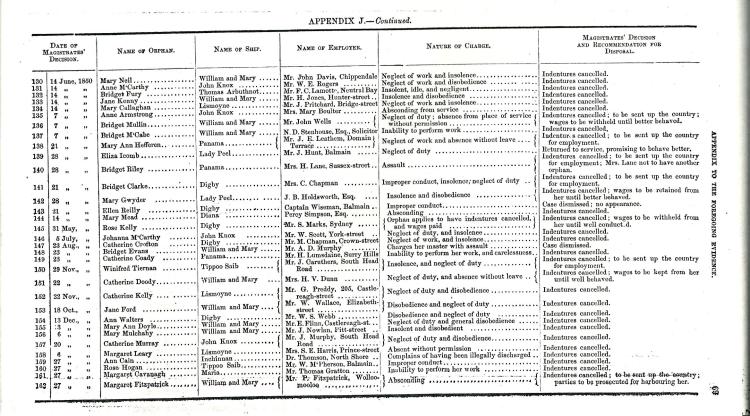

See entry number 150 of the table relating to cancelled indentures in blog post 22.

On the contrary, the tape gives a sanitized version of Winifred’s coming to Australia.

“…Grandma wanted to emigrate-the fare was only £1, but she had to wait until early 1850 when she would be 15, in the May of that year. She even had her birthday while on the ship. Her uncle (Owen Conlon) allowed her to leave then because of Bridgett Quigley her cousin.

Bridgett Quigley came with her, Grandma was a pretty girl, and Bridgett was charged with the the responsibility of looking after her. They sailed in the Tippoo Saib…Winifred went into Catherine Chisholm’s Camp and a position was found for her as a nursemaid for the children of a Mr and Mrs Morcom, school teachers at Bolwarra, Morpeth”.

There was no Caroline Chisholm ‘camp’ for Winifred to go to in 1850. And to be eligible for the Earl Grey scheme she had to be in a workhouse, for however short a period of time. Uncle Owen Conlon may well have had influence with Boyle Workhouse Guardians and officers, enough to get Winifred into the workhouse and on to the list of those chosen to go. People in Ireland were aware the scheme was coming to an end which added to their sense of urgency. But all that is merely hypothesis. We have no independent verification of any of it.

Nonetheless it does seem Winifred was related to Bridget Quigley.

On Bridget Quigley see http://irishfaminememorial.org/media/Bridget_Quigleys_life_in_NSW_24_Nov_2012.pdf

The account of Winifred’s emigration to Australia in the transcript was more personally acceptable than the reality of her having spent time in a workhouse or being sent up country after cancellation of her indenture for ‘insolence’. People often hid the fact they had spent time in a workhouse. It was a badge of undeserved shame. I’d suggest we may need help separating what the grandmother said, and what the granddaughter added to that transcript.

All this raises a question about the reliability of oral evidence, and how we go about appreciating its value. It is worth exploring. Simply type ‘Oral HistoryAssociation of Australia‘ into your search engine and you will find some helpful links. For the enthusiast who would like to take this further, there are some brilliant essays in The Oral History Reader edited by Robert Perks and Alistair Thomson, Routledge, 1998.

Winifred Tierney/Tiernan and David Masters

Winifred married Sussex born David Masters in an Anglican church in Morpeth in 1853. David had come to Australia with his parents and siblings in 1838 on board the Maitland, a voyage which saw 35 deaths, 29 of them children, mostly from scarlet fever. None of David’s family died.

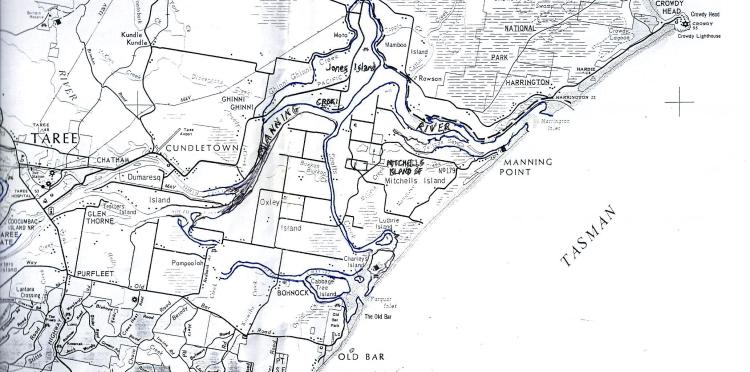

The Masters family settled in the Hunter Valley, and it was in the same area that Winifred and David’s first two children were born. Sadly, their first child, Mary, died in infancy. According to ‘our’ transcript and the barely legible notes of my conversation with Alan, the family, sick of being flooded out so frequently, moved north to the Lower Manning Valley. There, too, their first farm on Jones’s Island was subject to flooding, forcing a move to higher ground on Mitchell’s Island. It was here the rest of their children were born. Winifred was surrounded by, and absorbed into families from Sussex. David inherited a farm of thirty acres to which he added a purchase of another forty-four acres.

Here’s is Alan’s map showing where they lived. Their children were born, lived, married and buried in the same area, in Ghinni Ghinni, Wingham and Taree, most of them returning to Mitchell’s Island to be buried.

Alan and I talked about the importance of putting Winifred and her family into context, into a ‘place’. And finding local histories and local historians who might help with that. Luckily the area is well served for anyone wanting to develop the story further. I managed to note down the following, W. G. Birrell, The Manning Valley, Landscape and settlement 1824-1900, Jacaranda Press, 1907(?); Helen Hannah, Voices a Folk History of the Manning Valley, Newcastle, 1988, and importantly, the excellent local history, John Ramsland, The Struggle against Isolation A History of the Manning Valley, Library of Australian History in association with Greater Taree City Council, 1987. In the early days of white settlement, the Manning was a cedar getting area and later one of dairy-farming. Most of those who settled here, says John Ramsland, were not people of capital.

John Ramsland’s work tells us how in the period Winifred and her family settled in the Manning Valley, the main urban centres were beginning to take shape. ‘The first shelters in Taree (where many of Winifred’s children were to live) were temporary huts made of locally collected bark or tents made of calico. These were soon replaced by split slab huts with bark roofs and dirt floors. And soon after sawn slab huts made their appearance with shingle roofs, and wooden floors and glazed windows‘ (p.49).

It wasn’t till the twentieth century that Winifred and David’s family went further afield. Alan’s own impression was of nutritionally good stews, kitchen and pantry built together, refrigeration coming late, of spartan and relatively ‘isolated’ living.

According to John Ramsland the lower Manning Valley was a very Protestant area. The Masters had a strong Methodist connection but by way of ‘compromise’, our transcript tells us, David and Winifred’s children were baptised in an Anglican Church. Winifred, a young Irish Catholic lass, was absorbed into mainly Protestant Sussex families who had migrated together on the Maitland and the Argyle. Nonetheless she kept a link with Ireland through her younger sister Catherine. Catherine arrived by the Cressy in 1856.

“Catherine often visited the farm on the Manning River. If one of the girls was being married, she would arrive with all the materials and know-how to help with the trousseau. If it was one of the boys then her present was £50 towards his own farm. In 1894 Catherine and her husband (William Hillas) went for a trip to England and Ireland. While she was there she visited the site of the old home. She went by cab, and took a cut lunch. Only the fireplace, front and back doorsteps and the stone grating in the kitchen floor remained. She could remember which flag had to be lifted so her father could get into the cellar where he made his corn liquor…”.

Not a third-class or fourth class dwelling then, to use the terminology of Ireland’s census takers. I wonder in what ways this trip of Catherine’s may have influenced Winifred’s own memory of things, and what appears in the transcript.

Unfortunately I have been unable to make contact with Alan again. He has rich pickings for a good extended family history, one that that would do Alison Light proud. [Type Alison Light into the search box that appears after the comments to this blogpost to see what I’m on about ].

For me, Winifred’s story is another little life breath demonstrating how adaptable and resilient an orphan ‘girl’ could be. Our orphan histories are as diverse as the human condition itself. Maybe we should think of adding some more. That Hyde Park Barracks monument should be kept alive.

——————————————————————————————

Post Script.

I’m currently reading a powerful, poetic, tragic, brilliant work of fiction about a young girl during the Famine, which I heartily recommend, Paul Lynch’s Grace, Otherworld, 2017.

She looks around the table, sees the way the youngers stare at her, sees what is in …the whites of all their eyes and the who they are behind that white and what lies dangerous to the who of them, this danger she has feared, how it has finally been spoken, how it has been allowed to enter the room and sit grinning among them” (p.14).

You must be logged in to post a comment.