SUEY TAGGART

Given a preference, we like to feel good about what became of the Irish orphans in Australia. Sadly, our human canvas is not always sunshine and pretty flowers. Or cute little children, and young women overcoming the odds. If we take off our rose-tinted glasses and peer into the dark shadows of our canvas, who and what do we see? Mary Littlewood screaming and cursing at her fate? A battered, broken and abused Mary Coghlan? Catherine Toland in her own valley of tears wearing the darkest sackcloth and grief? Ellen Leydon worn out, tired and confused in a mental hospital or benevolent asylum?

Still, often we know these things only because their descendants were brave enough to bring them to light, give them recognition and pay them homage. Thank goodness the history, or rather histories, of the Earl Grey Irish female orphans is a co-operative effort.

Without the work of a family historian, the story of Susan (Suey) (Mc) Taggart would not be told. Thank you Norma Gardner–who told me about Suey, way back in 1987. Suey was the eighth child of Margaret Dempsey and Thomas (Mc) Taggart. Norma suggested Thomas dropped the Mac part of his name because people could not spell his name, or more likely, did not understand his accent.

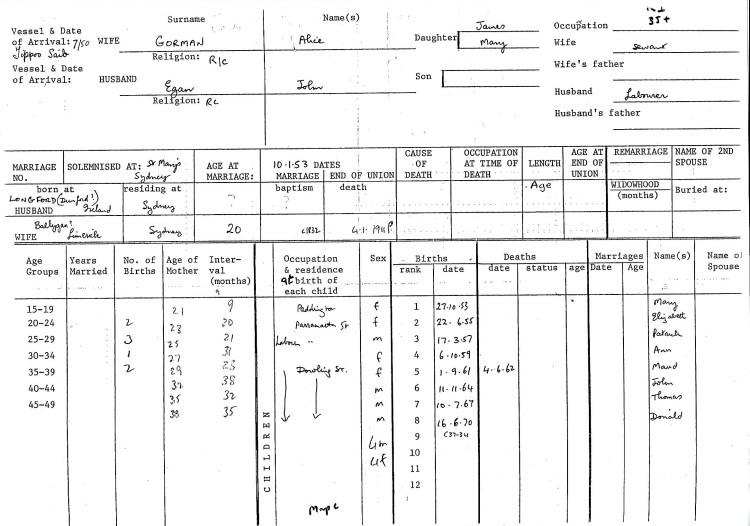

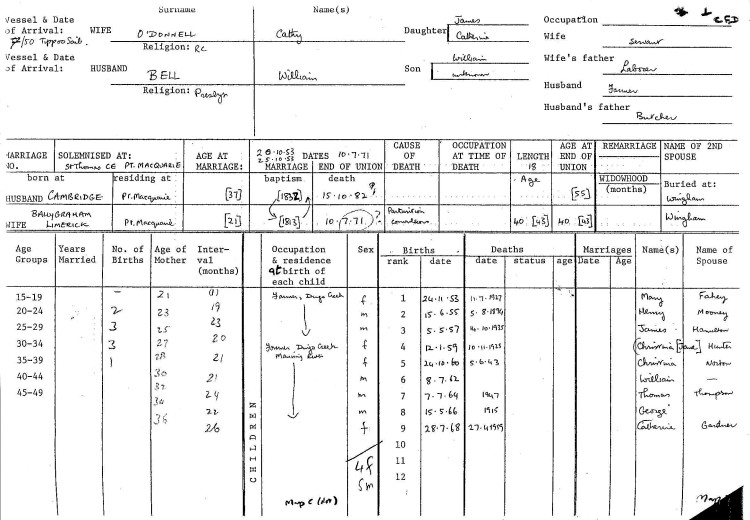

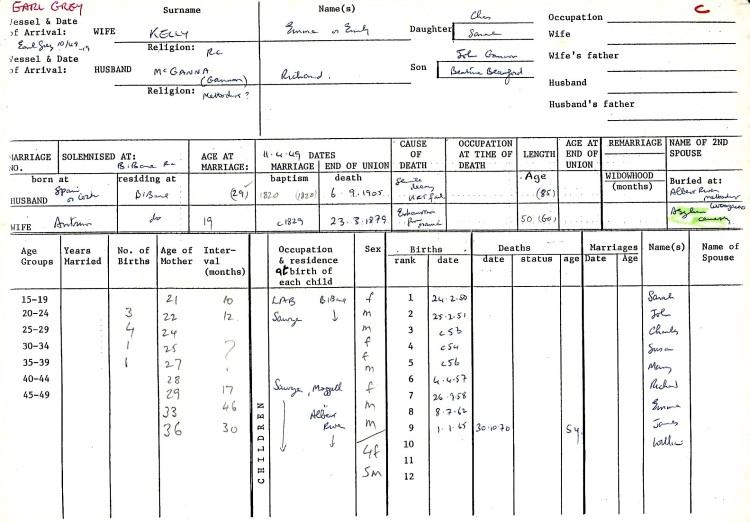

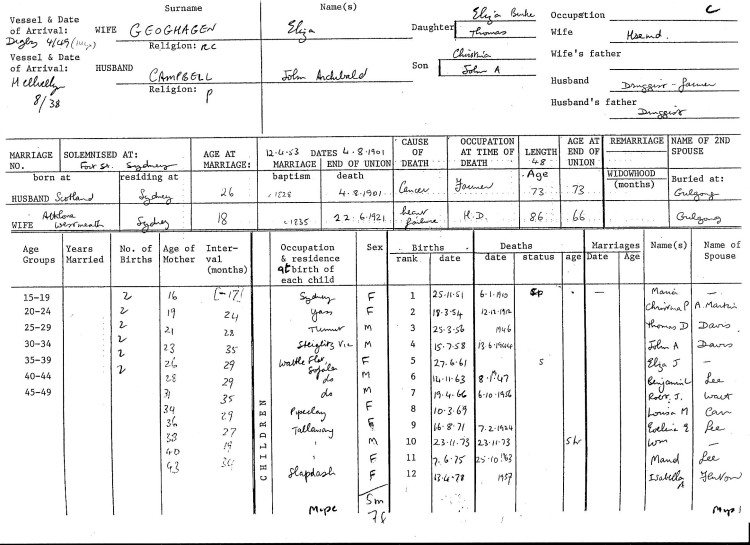

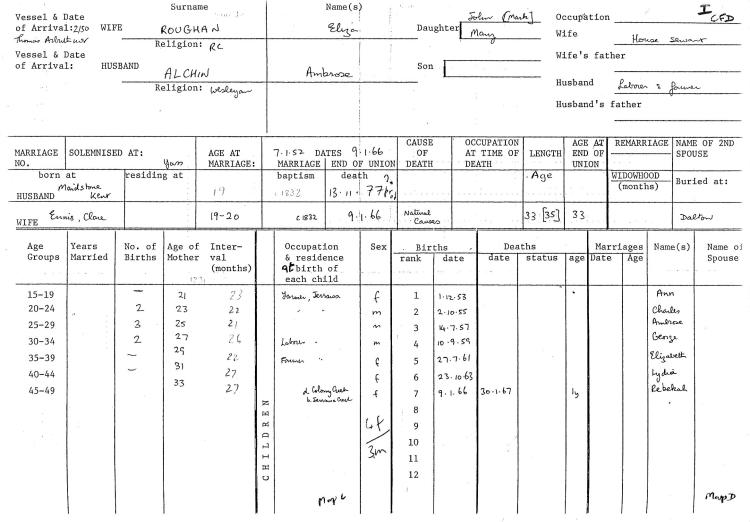

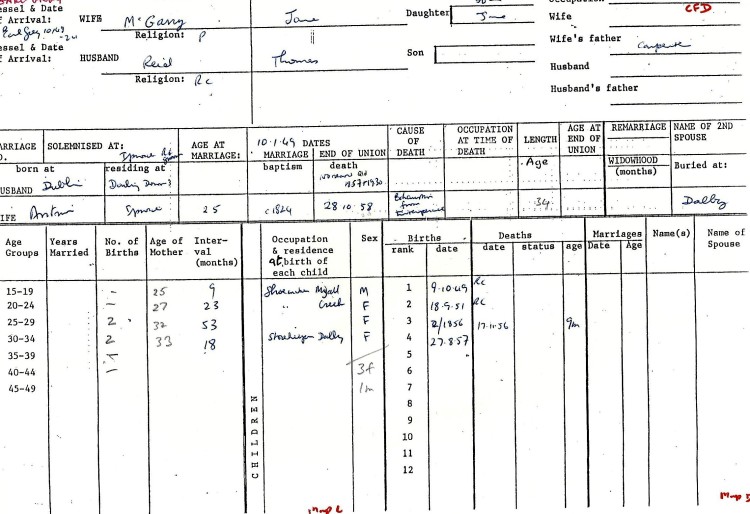

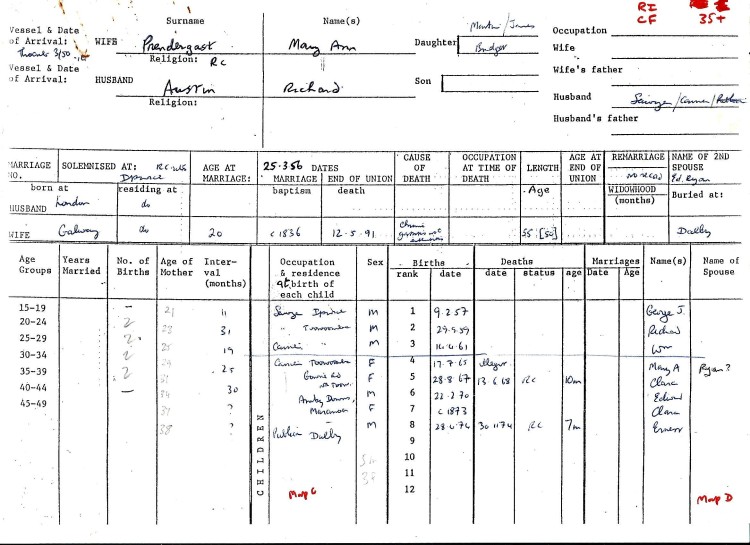

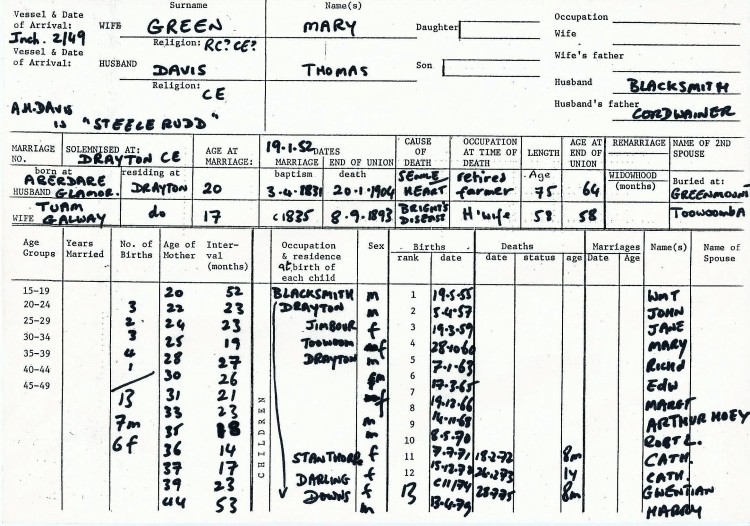

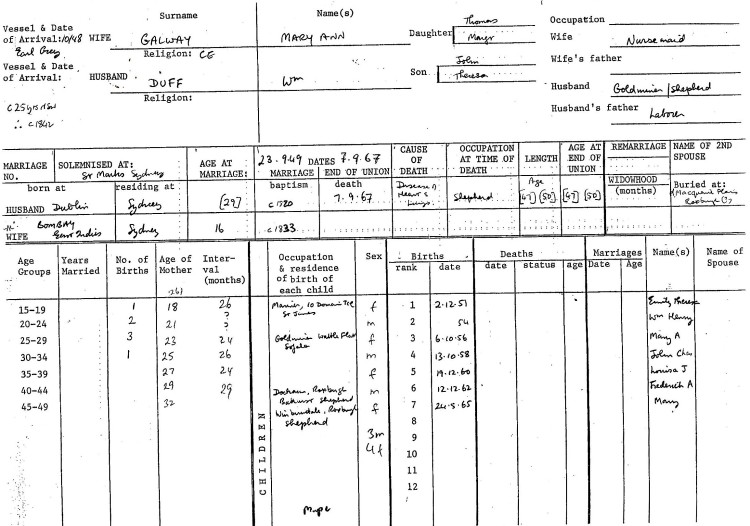

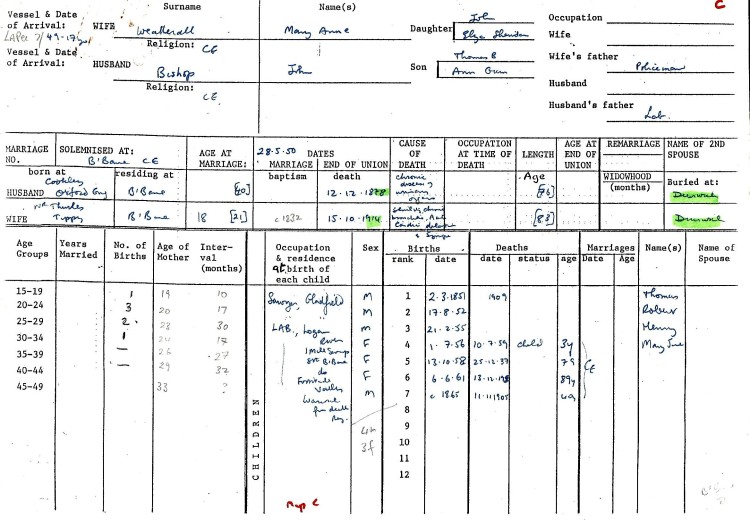

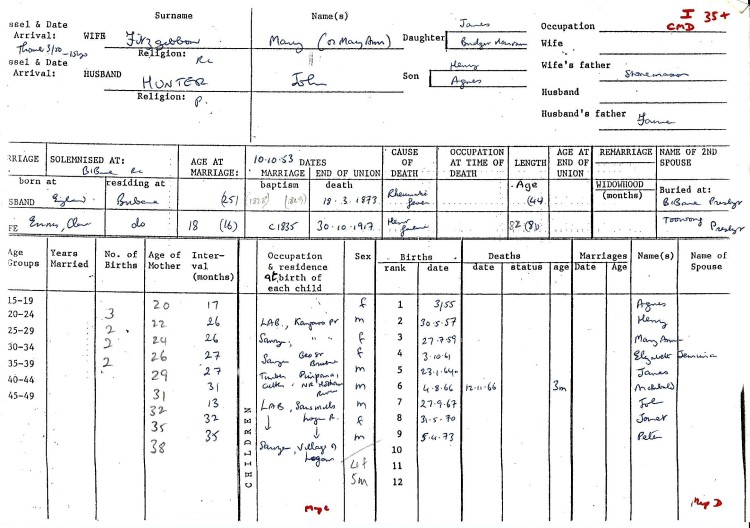

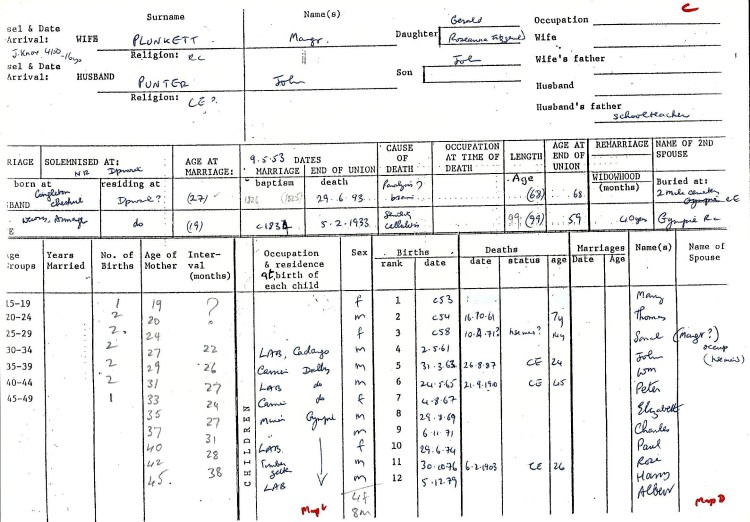

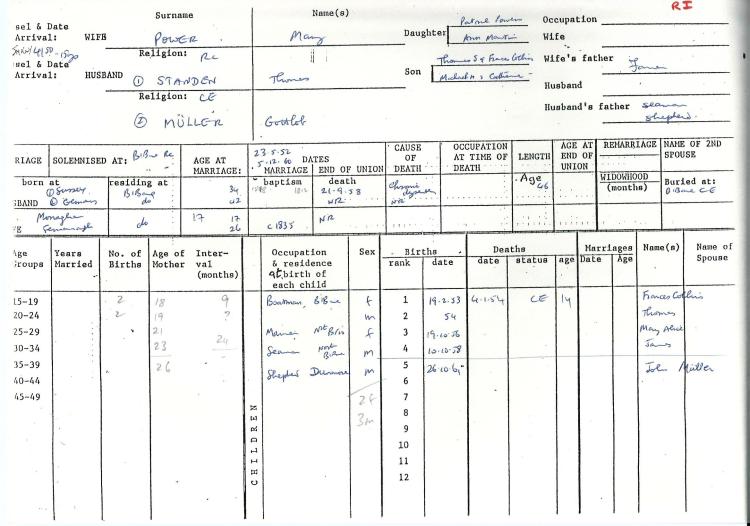

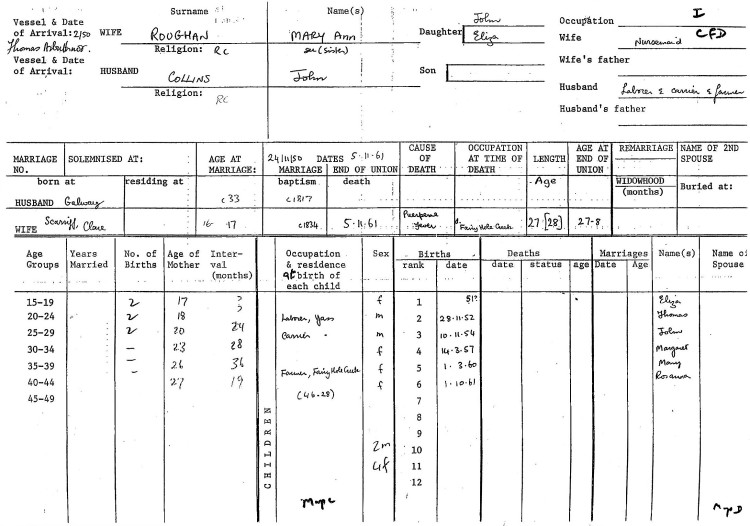

Margaret Dempsey was one of the Earl Grey orphans who arrived in Port Phillip in August 1849 by the New Liverpool. She was from the Clonmel workhouse in County Tipperary (http://www.workhouses.org.uk/Clonmel/), and listed on the ship’s manifest as an eighteen year old house servant who could neither read nor write. A month later, in September 1849, she was among a group of orphans making their way to Port Fairy on the steamer Raven where she would soon be employed by a Mr Urquhart at a wage rate of £10 per annum. However, by the 10th of March 1850, she was in the Roman Catholic Church at Yangery about 16 miles from Port Fairy, marrying a Scottish Presbyterian, Thomas McTaggart. We’ve been able to put together a family reconstitution of sorts:

As you can see, the couple had twelve children, 9 girls and three boys, all of them born in what was then north of Melbourne, Keilor and Epping. In 1856, Thomas bought a small block of land in Epping, and built rooms around the tent the couple were living in, as was the custom. The house and land has passed down the male line and, at the time Norma wrote to me in 1987, a Taggart was still living in the ‘new’ house that had been built on the same block.

Look closely at the family reconstitution, and you will see that ‘Susanna’, our Suey, born in June 1861, was dead by January 1882. What on earth had happened? Norma suggested in her letters to me that “poor Susan had her love affair one hundred years too early; how time changes all things”. Made pregnant by her lover, rejected by her mother and father, and in despair, she took her own life. Here’s the documentary evidence we have. See what you can make of it.

This is Suey Taggart’s suicide letter. I have taken the diminutive form of her name from her signature. But perhaps it should be Susey. What do you think? Along the right hand side is something illegible in this scan; it reads “don’t look for me for I have drowned myself“. Here is the transcription Norma made; you might like to check it for yourself.

The letter and the result of the inquest into Susan’s death were reported widely in the press, in January 1882–in The Age, The Ballarat Star, Riverine Herald, The Leader, The Horsham Times and the Mount Alexander Mail. You can read these via Trove https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper Click on Victoria and put “Susan Taggart” into the search box. If you find it hard to decipher any of these, let me know your troubles.

Occasionally a bit more information is reported in the newspapers. For instance, the Riverine Herald 23 January 1882, page 3, has Mrs Pickett stating, “I went in [to Melbourne] after her, and found her at the wood market talking to Bill Heddle, who resides out here.”

Here are the depositions from the inquest.

The Magistrate at Nillumbik found ‘the cause of death was drowning, evidently caused by the deceased’s self-destruction“.

Now let me challenge your historical imagination, what do you think happened here? See if you can piece together Suey’s story. Take some fictional liberty if you think it improves your story. Others will be better placed than me to go inside Suey’s head and understand what she was going through. Poor mite.

When she was nineteen Suey had gone to work as a servant at the Diamond Reef Hotel at Nillumbuk, north of Melbourne. Her employers, Margret and Edmund Pickett were good to her. Mrs Pickett was delighted watching the excitement and happiness of young Suey when she fell for a local lad, Bill Heddle, a patron of their hotel. But in that flush of excitement and wonder Suey had fallen pregnant. When she realized her period hadn’t arrived two months in a row, she went home to her parents who lived not far away in Epping. Surely, at Christmas, mum and dad would look after her and help her have her baby. But her dad rejected her, called her a slut who brought shame on them all, and sent her packing. [Norma suggested since Thomas was not even mentioned in Suey’s suicide letter, he must have been a hard man]. Desperate now, Suey followed her Bill to Melbourne pleading with him to take her back. But he too, useless coward that he was, spurned her. ‘What do you think I can do? It’s over. It’s over between us’.

Mrs Pickett who had learned where Suey had gone, travelled all the way to Melbourne, and found them arguing at the wood market. She insisted Suey came back with her to the Diamond Reef Hotel, where at least she would have a roof over her head and food in her belly. Shortly after, at the height of summer, feeling ill and with a splitting headache, Suey had gone to sit with Mrs Pickett and talked with her. What did they say? According to Suey’s letter, Mrs Pickett “‘told her the truth in every way”. ‘That Bill is every bit as responsible as you. You’re not to take all the blame. But you’ll have to raise the bairn on your own’. That same night Suey returned to her room. Feeling abandoned and alone, broken-hearted, and carrying a crushing guilt, she decided to end it all. Desperate for her mother’s forgiveness, she’d do what she’d thought of doing for some time now. She’d had her photograph taken so people would remember her. Poison was her first plan. But the Hotel Water Tank was close by and easy to get to. She’d do it now, tonight, when everyone was in bed.

The next day, 16 January 1882, about 9.30 in the morning, a wood carter, Christian Erikson unceremoniously dragged Suey Taggart’s body from the Water Tank at the end of a meat hook. “I pity the poor girls who are brought to misfortune like I was“.

What’s your view? What do you think happened?

You must be logged in to post a comment.