Some time ago I asked John Moon would he like to write something for my blog, something about his orphan ancestor, Jane Hutchinson, and something about how finding ‘his’ orphan has affected him. He very kindly sent me the following. I’ll keep the two parts he sent, separate. The second one I’ll put up a little later; it’s a little gem of creativity.

Part 1: Jane Hutchinson, Earl Grey Irish Orphan, “Derwent”, Melbourne, 25 February 1850

The basic facts about Jane Hutchinson are contained in her summary at the Irish Famine Memorial Website (which incorporates data from Trevor’s Barefoot and pregnant?). Given the dearth of accessible information about Jane’s life it is difficult to expand upon this summary without repeating some of the more general experiences of other Orphans. Thus all we can do is add some observations and speculations by considering two people living around her which by association adds to her story. These two people are Thomas Buckler, the man she married, and to a lesser extent Michael Madden, her first employer after “disposal”.

Name: Jane Hutchinson Native Place: Londonderry [Derry] [Desertmartin]

Age On Arrival: 16

Parents: Not recorded

Religion: Roman Catholic

Ship Name: Derwent (Melbourne Feb 1850)

shipping: house servant, cannot read or write;

Magherafelt PLU PRONI BG23/G/1 (3032), Jane Hutchinson, aged 13, single, RC, servant, from the Union at large, deserted, no means of support, came in with her mother, Ellen, aged 50, widow, mendicant with William 15, Nancy 11 & John all healthy but no means of support, entered 31 Oct 1846, left 6 Jan 1847; (6670) Jane Hutchinson, 15, single, RC, healthy, Desertmartin, labourer, entered 9 Jun 1848, left 30 Oct 1849

empl. by Michael Madden at Merri Creek, £9, 6 months;

married Thomas Buckler (seems to be convict to VDL per Maitland Jun 1846) on 25 Oct 1852, St James CofE Melbourne; 12 children; died 25 Jan 1908 Wangaratta, Victoria. (source https://irishfaminememorial.org/details-page/?pdb=7582

Jane and Thomas were the “guinea pigs” of two different nineteenth century socio-political experiments. In the case of Jane, it was Earl Grey’s Irish Orphans scheme, and in the case of Thomas it was the “separate system” of the 1839 Prison Act , implemented at Pentonville prison.

Thomas was born in Nuneaton, Warwickshire, England on 3rd December 1826.

From the available records and newspaper reports, it appears that the Bucklers were a “family in distress”. At the age of 12, Thomas’ second sister Rebecca died in the Chilvers Coton Workhouse and by the age of 15, the 1841 Census suggests that his mother and two sisters, Elizabeth and Mary, were resident in the same Workhouse. Neither Thomas nor his father appear to be in Nuneaton at the time of this Census which raises the question of where they were, or did they not take part in the 1841 Census.

After a a number of run-ins with local magistrates, Thomas, in December 1844, was tried, along with Joseph Martin (alias Randle), at the Coventry County Assizes for stealing 17 pairs of boots and shoes (value £3. 10s.), a small quantity of cheese and butter and a pair of scissors (value 10d.) and sentenced to 10 years transportation.

He arrived at Pentonville 23 December 1844 and was subjected to discipline under the “separate system”.

“The distinctive characteristic of the discipline was the COMBINATION of severe punishment with a considerable amount of instruction and other moral influences. The elements relied upon for severe punishment were, rigid separation , and a protracted term of eighteen months’ imprisonment, followed by transportation. The moral or reformatory elements were, frequent visitation by superior officers, a considerable amount of moral and religious instruction, combined with industrial training [in Thomas’ case shoe-making], and a reasonable prospect of earning an honest livelihood in the colony, upon the sole condition of steady good conduct. At that time, these elements of severity and kindness were combined at Pentonville in a higher degree than they have ever been combined in any other prison in Great Britain”. See Results of the System of Separate Confinement: As Administered at the Pentonville Prison – available for download in Google Books.

After around 18 months at Pentonville, Thomas boarded the Maitland as an exile, bound for Australia, arriving Melbourne 6 November 1846.

Thomas has the distinction of appearing in a House of Commons Parliamentary Paper, not by name but by number (#741), for the offenses he committed whilst on route to Australia. These included:

17 June 1846 Selling his clothes to a seaman in the prison for a chew of tobacco – put in irons five days.

10 August 1846 Chewing tobacco in the prison and spitting on the deck after bed-time. The second time he has broken through the rules – Bread and water, and made prisoner below for fourteen days.

So much for the intended behavioural changes of Pentonville – or was it a reflection of the severity of the punishment for what would now appear to be minor infringements?

As an exile, Thomas stepped on the shores of Port Phillip as a free man, “on condition that they do not return to “Our United Kingdom during the remaining term of their respective Sentences of transportation”. Initially, he went to work for a well-known auctioneer, founder of Kirk’s Bazaar and prominent turf club member, James Bowie Kirk of Bourke Street Melbourne.

We hear no more of Thomas until his marriage day in 1852.

Whilst I do not have a copy of Thomas and Jane’s marriage certificate (at $20.00 per certificate genealogy can become an expensive hobby), I understand that it states that they were from Campaspe River. So the question arises as to ‘how did they get there?’

For Thomas, as indicated above, we have no information. For Jane, one speculation is that she went there with the Maddens family (her first employer). In this respect, an obituary of Patrick Madden (son of Michael) in the McIvor Times and Rodney Advertiser, Thursday 7 June 1906 reported that:

The late Mr Patrick Madden, whose death was reported in your last issue was the oldest resident of Mia Mia and district. He was born at Campbellfield [Merri Creek], near Melbourne, on the 15th March, 1843, and came to Mia Mia with his parents on 1st February, 1851. … His father (the late Mr Michael Madden) was travelling with his stock from Melbourne to Mia Mia on 6th February 1851 (Black Thursday) and had some trouble to save them from being burnt.

Michael Madden perhaps rented some land from a pastoralist/ squatter in the area to keep his stock. In January 1854 (after Jane was married), Michael Madden and his wife had taken over the license of the Mia Mia Inn. Michael died a couple of years after purchasing the license to the Inn and is buried in Kyleton Cemetery.

The speculation here is that Michael Madden’s farm, where Jane may have been living, was located somewhere between Kyleton and Mia Mia on the Campaspe River.

Jane and Thomas were married on 25 Oct 1852 at St James CofE Melbourne [I notice from Trevor’s blog #58 a contributor stated that “St James in Melbourne was both Catholic and Anglican in the one church” – does anybody have any details of this arrangement?]. Following their marriage, it would appear that they went to Wangaratta, working for the pastoralist/ squatter Benjamin Warby Jnr. on his 23,000 acre run ‘Taminick’ (estimated grazing capability 700 cattle or 4,000 sheep).

It was at Taminick that Jane’s first two children were born – Sarah Jane in 1853 and William 24 March 1855 (details of the births of her remaining ten children are shown in the family tree below…see part 2).

Their third child Abraham was born in North Wangaratta in 1857, suggesting that they moved from Taminick to North Wangaratta some time between 1855 and 1857.

The obituary of William Buckler (son of Thomas Buckler) in the Wangaratta Chronicle, Saturday 1 September 1934, reported that:

The late Mr. [William] Buckler was born at Taminick and at the age of three [maybe two, as Thomas’ second son Abraham was born at North Wangaratta in 1857] he was taken to North Wangaratta by his parents, to property which was afterwards known as the “Old Buckler homestead”.

Here his father was first to grow wheat in the district, and the first year there there was obtained just one ear, and in the following year the whole of the previous year’s production was planted, to gain about one bushel of wheat [probable a little poetic/ journalistic licence]. The ground was tilled by a wooden plough made by Mr. Thomas Buckler.

Details of Thomas’ land acquisition are probably held in the bowels of the Public Record Office Victoria (PROV) the location of which could possibly be identified in Nelson, P. and Alves, L. “Lands Guide: A guide to finding records of Crown Land at Public Record Office Victoria”, Public Records Office Victoria, Melbourne, 2009. However, without access to PROV we rely on scattered newspaper reports.

The Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic.: 1855 – 1918), Saturday 27 October 1866 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article198659284 reports that:

A commission of enquiry into applications for land under the forty second section of the Amending Land Act, was held on Thursday (25 October 1866), at the Plough Inn, Tarrawingee. The commission consisted of Messrs Gaunt, P.M., and Mr H. Morris, District Surveyor. The proceedings commenced shortly before eleven o’clock [one of its decisions being]:

PARISH OF CARRARAGARMUNGEE

Thomas Buckler applied for eighty acres. He has a wife and six children. He has seventy-one acres of purchased land, but none leased – Recommended.

Thus by 1866, Thomas had purchased seventy-one acres and had been recommended for the lease of a further eighty acres.

On his death Thomas had 302 acres of which 282 acres were transferred to Jane and 20 acres sold to his son Abraham (blacksmith) for £70.

By 1879, Jane had had twelve children, eleven of whom lived long lives.

Whilst Jane could neither read nor write (even her will dated 20 December 1907 was read to her before witnesses and signed with her mark), the education of the children was not neglected. In 1867, the Ovens and Murray Advertiser, reported on the examination of pupils attending Wangaratta National School. The subjects examined included: reading, writing and spelling, arithmetic, grammar, geography, history, English composition, Latin, and mental arithmetic as well as a prize for girl’s needlework.

The impact of this education was passed down through two generations where Jane’s Daughter Louisa insisted that during her annual six week Christmas holiday visits, her granddaughters could recite by heart a poem. Two of these were Ella Wheeler Wilcox’ “The Two Glasses” http://www.ellawheelerwilcox.org/poems/ptwoglas.htm and George Webster’s “The Story of Rip van Winkle” https://ufdcimages.uflib.ufl.edu/UF/00/08/54/12/00001/UF00085412_00001.pdf (Louisa was a teetotaler).

Jane died on 25 January 1908 and is buried with Thomas at Wangaratta Cemetery.

Jane, who in her adolescence was a pauper, lived to the age of 75, bore 12 children and owned a farm of 282 acres. This must have been beyond the wildest dreams of the adolescent Jane. When I look at this brief sketch of Jane’s life, I cannot but think “very brave girl and a true Australian pioneer”. When I look back to the Magherafelt Workhouse, I also cannot help thinking that she took advantage of the third Earl Grey’s Irish Orphans scheme, and was not a victim of it.

Thomas on the other hand did not have much choice. He grew-up in a family under stress and once he was caught for stealing the boots and the cheese the system of the day determined his future. After arriving in Australia however he rose to the challenge and through hard work was able to make a success of his life – another true pioneer.

(As a footnote, it is observed that while in Wangaratta he seems to have had only two run-ins with the law: one for being drunk for which he was cautioned and discharged and the other a traffic infringement “leaving a horse and dray unprotected in the public streets” for which he was fined 2s 6d, with 5s costs).

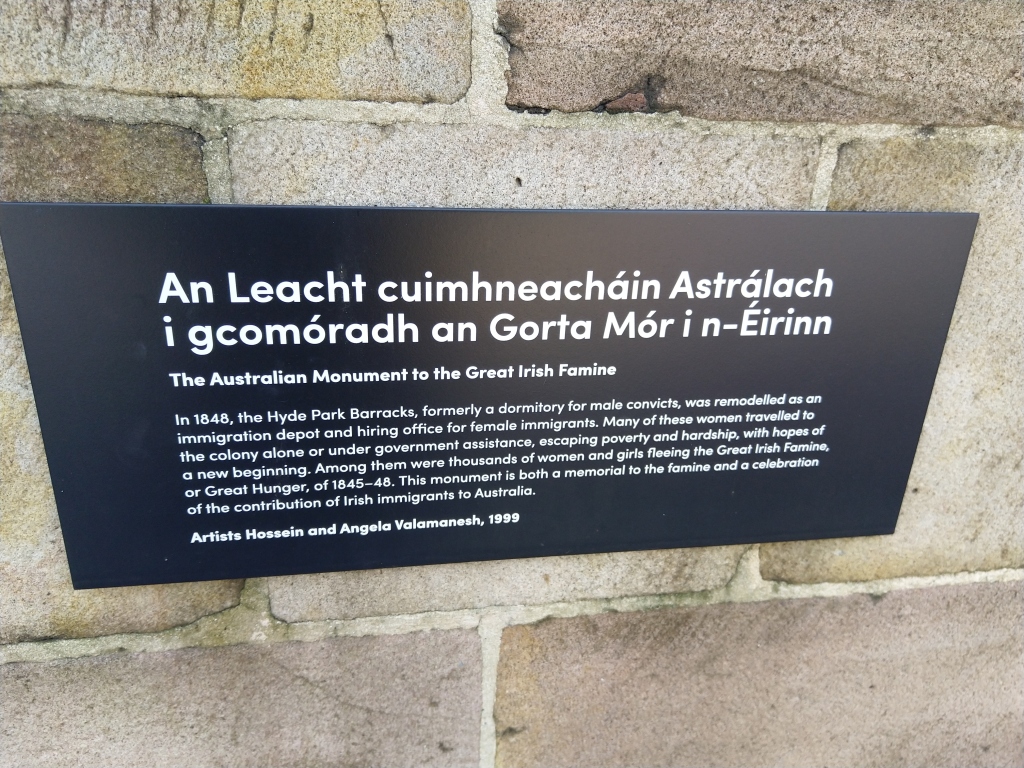

Just a reminder about this year’s annual gathering at the Famine monument.

You must be logged in to post a comment.