Some Port Phillip orphans

Here are details of some of the orphans who arrived or settled in Victoria, from my family reconstitution work. They may be of interest to anyone going to the commemoration in Burgoyne Reserve, Williamstown on 19th November 2017. My best wishes to all taking part.

I hear there are moves afoot to set up an Outreach programme. That is brilliant news. Here’s to everyone looking forward…to helping others…in memory of the Port Phillip orphan ‘girls’.

There is lots of information on the www.irishfaminememorial.org database about the Port Phillip orphans. It is well worth your ‘mining all within’. Maybe someone can tell me where all the information is from?

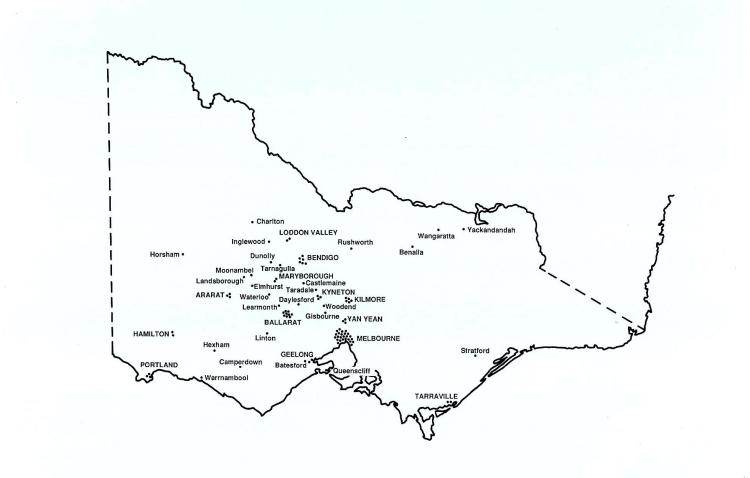

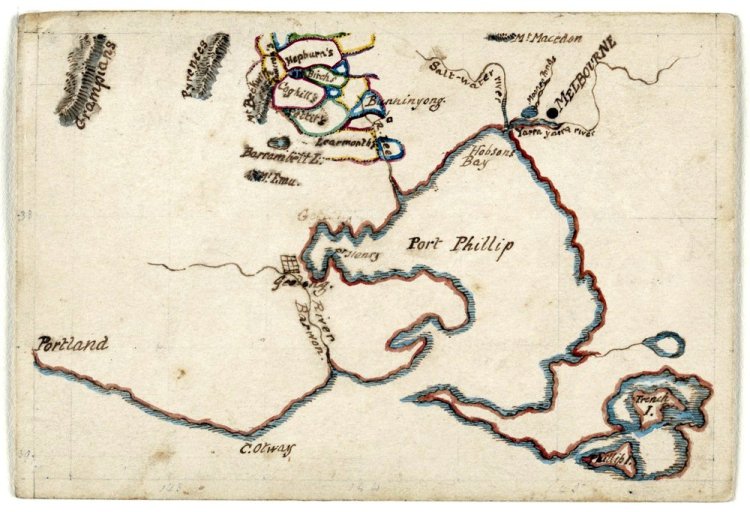

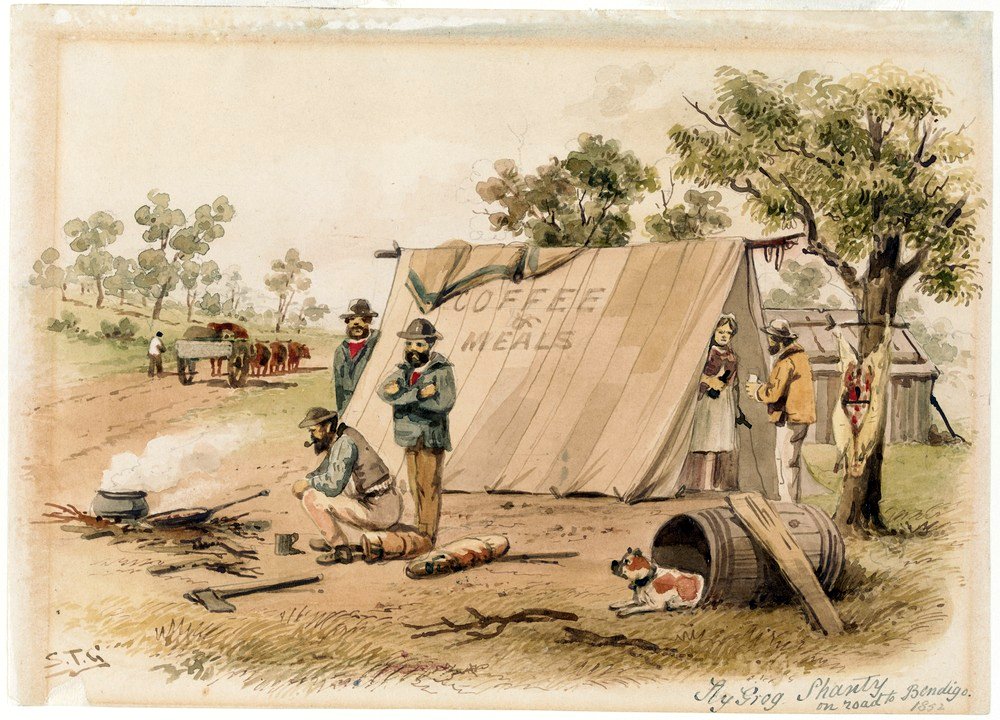

From my map showing the location of the orphans in Victoria, c. 1861 (from the birth/baptism dates of their children) one cannot help noticing how the orphans and their family were attracted to the gold fields. And yet they arrived in Port Phillip before the discovery of gold. Colonial authorities moved some orphans away from Melbourne, to Geelong, and to the Western Districts via steamer, to Portland. So not every orphan went to the diggings, though undoubtedly many of them did, even from Portland. See if you can identify which ones did not, from the reconstitution forms below.

[I recently discovered that you can no longer make these images larger using an ipad. Pinching the image doesn’t work. It must be the template I’m using. Bummer. I wonder how I might remedy this.]

“

“The first glance at the great and glorious gold-field of Ballarat we got was the celebrated Canadian Gully, then radiant with the still fresh fame of the enormous 137 lb. nugget”, (William Kelly, Life in Victoria 1853…1858, , Historical Reprint Series, Kilmore, 1977, p.178.)

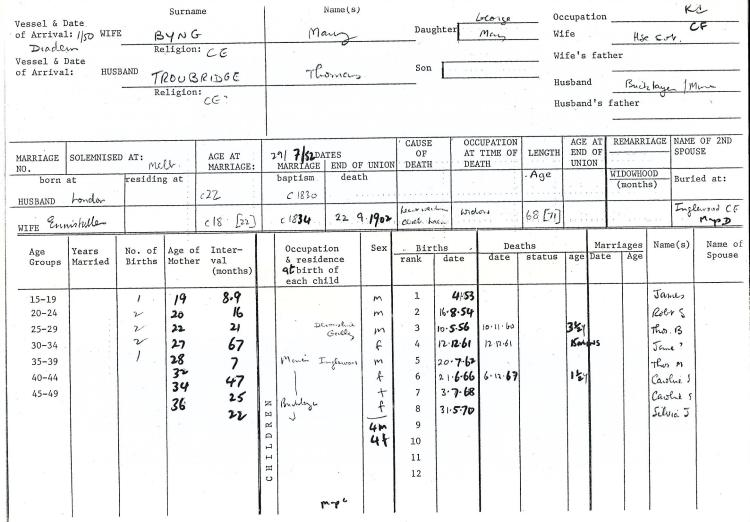

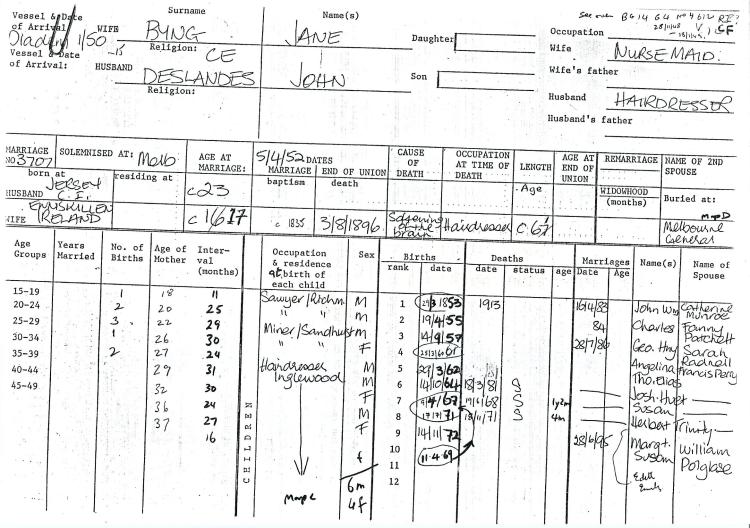

Mary and Jane Byng from Enniskillen per Diadem

Enniskillen workhouse sent a comparatively large number of orphans to Australia by the Earl Grey scheme. 16 year old Mary Bing came into the workhouse 28 November 1848 as part of a large family group comprising 50 year old George Bing from Enniskillen Asylum, (George left the workhouse 5 September 1849), 48 year old Mary Anne, young Mary’s sister Jane, who was 14, and siblings William (11), George (10) and Catherine (5). Mary and Jane left the workhouse 3 October 1849 on the way to Plymouth to join the Diadem. (Public Records Office of Northern Ireland, BG14/G/4 [4611 and 4612]).

Both sisters went with their husbands to the Victorian gold diggings, and for a time at least settled near to one another, in Inglewood. Three of Mary’s children died at a young age. Jane lost two children when they were less than two years old, and her son Joshua when he was sixteen. My thanks to Nancy Pilat and Michaela Rosenberg for the original information. I must have had access to vital statistics to fill in some of the dates.

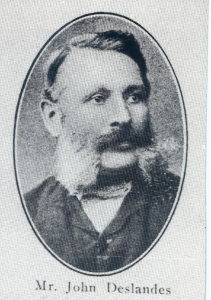

Jane Byng

Mary Doherty from Carrick-on-Suir per Eliza Caroline

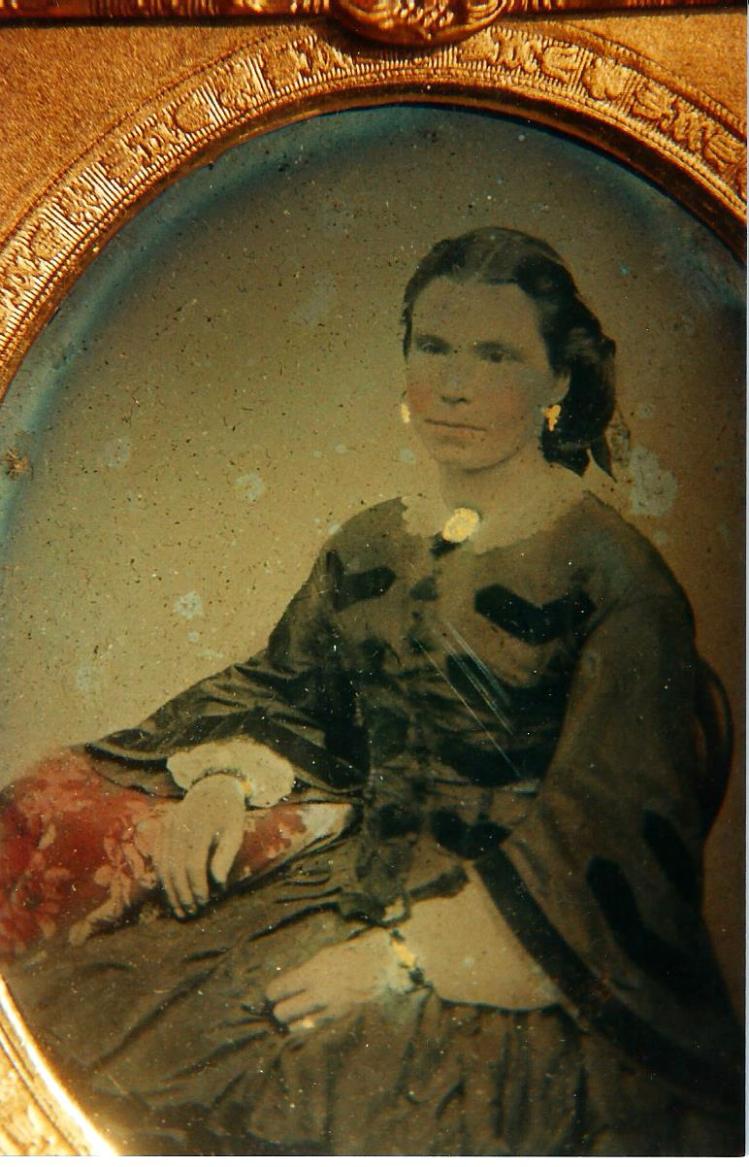

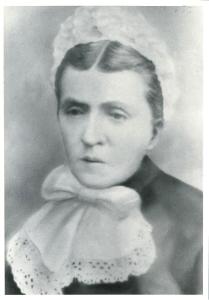

Here is what is on the www.irishfaminememorial.org database about Mary. Mary’s details, including the lovely photograph, originally came from Margaret Murray who was a teacher at East Doncaster High School. Margaret told me that William, Mary’s first child by Ray Salt took the surname Ranson. Some of the Eliza Caroline orphans would do well for themselves.

- Surname : Doherty

- First Name : Mary

- Age on arrival : 16

- Native Place : Carrick on Suir, Tipperary

- Parents : Not recorded

- Religion : Roman Catholic

- Ship name : Eliza Caroline (Melbourne 1850

- Workhouse : Tipperary, Carrick-on-Suir

- Other : shipping: nursemaid, reads; Empl. Mrs Rachael Ackerman, Corio St., Geelong West, ₤10, 6 months; married 1) Ray Salt at St Mary’s Geelong, 8 Jan 1852, 1 child; married 2) Samuel S Ranson, Ararat, 19 Jul 1859; 6 children; husband a farmer on the Wimmera at Elmhurst. He left his estate to two sons after bequests totalling ₤500 to his other four children; Mary died 21 Dec 1913.

I wonder when and where this photograph of Mary was taken. She looks quite young, does she not?

Mary Doherty

Let me see if I can find some more of my family reconstitutions for the Eliza Caroline. Note that these completed family reconstitutions favour those in long-term stable relationships.

Margaret Ryan from Nenagh per Eliza Caroline

Margaret married David Murray, a Scot, whose religion was different from her own. They had twelve children together, at least two of whom lived a long life. From what my informant Kevin Murray told me, David rose from being a farm labourer to a farm owner. Margaret might even have witnessed the women rioting in Nenagh workhouse in 1849. In Nenagh, women were the leading characters in the protest over food and entitlements, ‘dashing saucepans, tins and pints of stirabout to the ground and smashing windows’. Margaret and David are both buried in Balmoral in the Western District of Victoria.

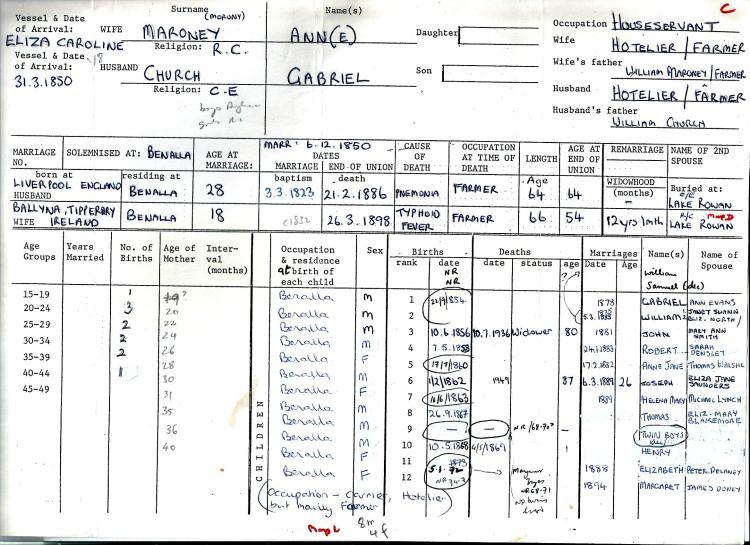

Ann Maroney from Ballyna, Tipperary per Eliza Caroline

Ann married within nine months of arriving in Port Phillip. Her husband also had a different religion from hers. Together they had twelve children, the boys raised as Anglican, the girls as Roman Catholic. Ann’s estate was valued at £801 when she died. She was a widow for twelve years, and apparently a good farm manager. Both Ann(e) and her husband are buried at Lake Rowan. I wonder how she got to Benalla so quickly. It would appear she and her husband did not go looking for gold. Considering where she lived, she must surely have been aware of Ned Kelly’s mob and their doings. (Incidentally, there’s some very good historical fiction on the subject. I’m thinking of Jean Bedford’s “Sister Kate”, Penguin, 1982, Peter Carey’s “True History of the Kelly Gang”, UQP, 2000 and Robert Drewe’s “Our Sunshine”, Macmillan, 1991. Ian Jones’s, Ned Kelly. A Short Life, Thomas Lothian, Port Melbourne, 1995, will provide a good historical context).

My thanks to Brenda Cooke for the original information for Barefoot vol. 1. She also supplied the names of the children’s spouses.

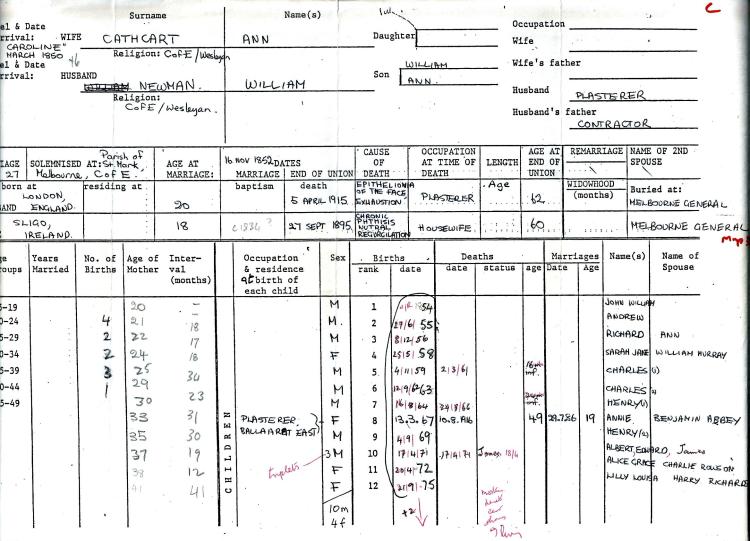

Ann Cathcart from Sligo per Eliza Caroline

Ann married William Newman, a Londoner, within three years of her arrival in Port Phillip. They had fourteen children, including triplets Albert, Edward and James, one of whom appears to have died at childbirth and another, James, a few months later. That made four of their children dying in infancy. They tried their hand on the goldfields, without much success but William had a trade to fall back on: he was a plasterer. Both are buried in Melbourne General Cemetery.

Charles Norton map Port Phillip and around courtesy State Library of Victoria

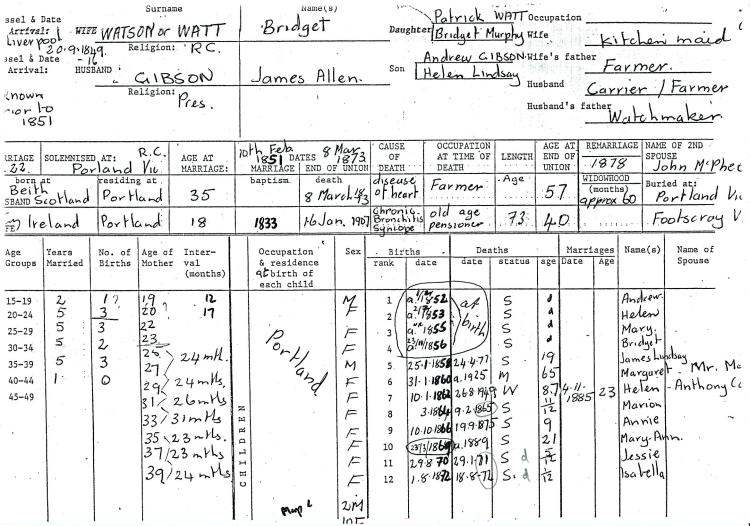

Bridget Watt or Watson from Milltown, Kilkenny per New Liverpool

Bridget, originally from Kilkenny, was one of those who went to Portland. Notice she lost her first four children at childbirth. I wonder if Bridget’s famine experience affected her child-bearing capabilities. Janet Mc Calman in her Sex and Suffering (Melbourne U.P., 1998) describes the effects of malnutrition on young Irish women giving birth at the Royal Women’s Hospital in Melbourne. Malnutrition and poverty had led to underdeveloped and deformed pelvises. Once the women had a better diet, rest and sunshine in Australia, their babies grew larger in the womb, making for a difficult birth. The procedures involved, including craniotomy, were gruesome.

Most of Bridget’s twelve children were dead before they reached the age of 21. Only two survived beyond 60. According to Lorraine Thomas, Bridget’s descendant, all of Bridget’s children were born in Portland. After her husband died in 1873 she remarried, this time to John McPhee. She is buried in Footscray.

Bridget Flood from Cappoquin, Waterford per Eliza Caroline

My thanks to Claire Palmer for the photograph of young Bridget Flood. Bridget was 16 when she joined the Eliza Caroline. She was first employed by a reporter from the Melbourne Morning Herald, Edward Flood of Spring Street. I wonder was he related. 11 July 1853 she married a widower Joseph Plummer in St Peter’s Anglican Church. She had six children, four of whom survived to adulthood. She died in 1884 aged 52 and is buried in Melbourne General Cemetery.

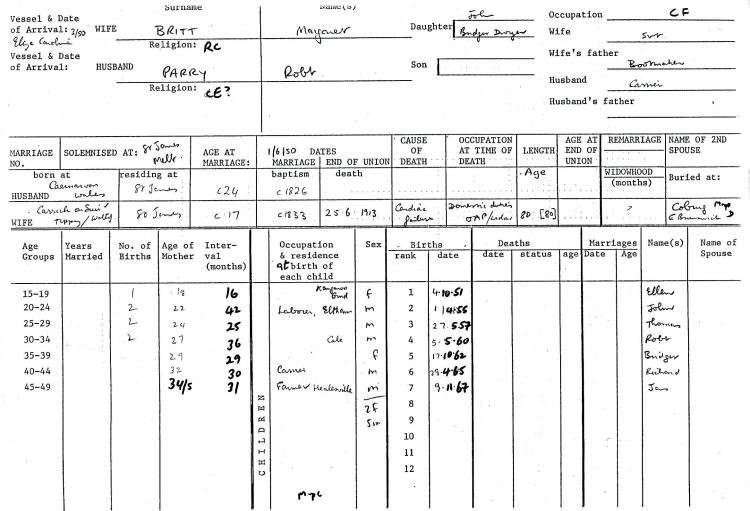

Margaret Britt from Carrick on Suir, Waterford per Eliza Caroline

Margaret married a Welshman Robert Parry, only two months after her arrival. They had seven children, two girls and five boys, born at various places, Kangaroo Ground, Eltham, Cale, and when Robert was a farmer at Healesville. Margaret died in 1913 when she was 80 and is buried in Coburg, East Brunswick.

Catherine Rooney from Sligo per Eliza Caroline.

Catherine was sixteen when she went on board the Eliza Caroline. After 25 days in the immigrant depot she was employed, for three months, at a rate of £7 per annum, by John Green of Little Bourke Street. She married in 1852 John Dowling a farmer from Colac with whom she had nine children. She died in 1904.

Catherine Rooney per Eliza Caroline

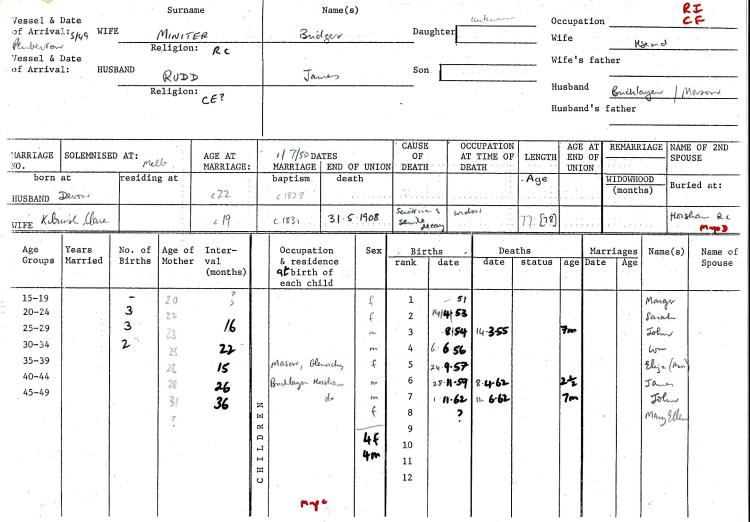

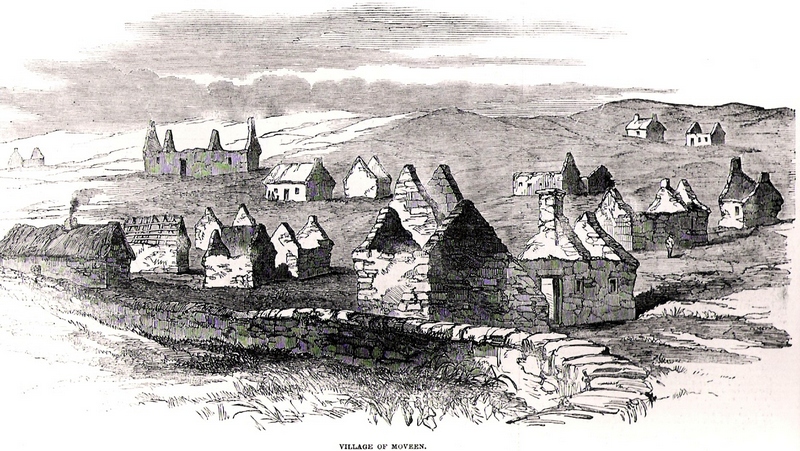

Bridget Miniter from Kilrush

Unfortunately I don’t have much on the orphans who came from Kilrush. There is something about Bridget Miniter at the back of my mind but it escapes me at the moment. Was it something a descendant had told me? Bridget married a lad from Devon who was both a mason and bricklayer. I suspect some of those such as Bridget, who ended up in the Western Districts of Victoria went first by steamer to Portland and later travelled north from there. Bridget and James had eight children, four boys and four girls, but three of the boys died in infancy or childhood. She herself lived until she was 77 or 78. She is buried in the Roman Catholic section of Horsham cemetery.

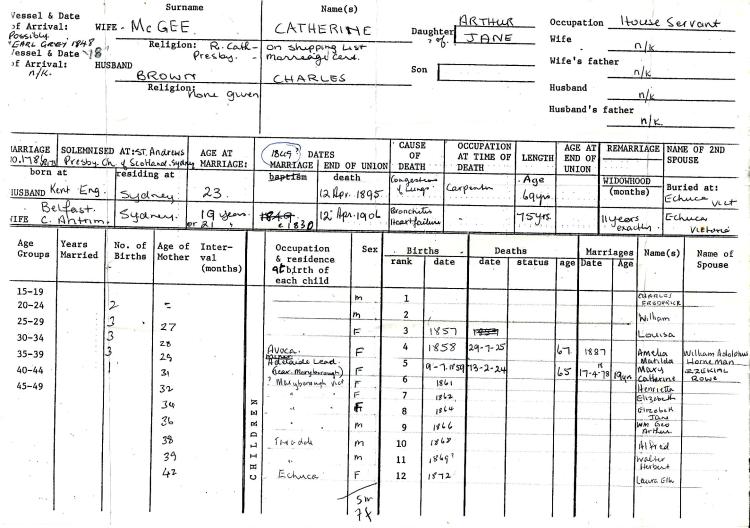

Catherine Magee/McGee per Earl Grey

Just one more to finish. It is a reminder that many of the orphans did not remain near the port of their arrival. Kerry Cory told me about Catherine Magee/McGee recently, “Catherine and Charles went to the Victoria Goldfields and finally settled in Echucha Victoria with the remaining 7 of her 12 children, but unfortunately her 11th child died while working at the saw mill with his father. I have visited the graves at Echuca and the site of where they may have lived on the Murray river at the old saw mill on the Golburn rd. They are all buried together in an unmarked grave. When I get more information together the historical society are going to assist me in placing a marker and adding Catherine to their history tour because of her Earl Grey past“.

I eventually found what I had for Catherine; my original informant was Norma Sims of West Brunswick.

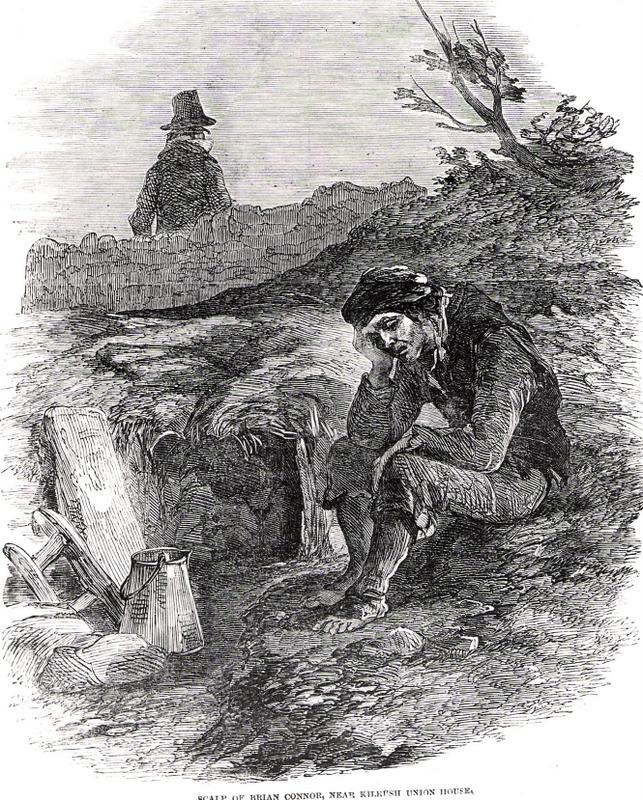

The following is from the entry in Barefoot vol. 2, p. 149. I’d found Catherine in the Antrim Workhouse Indoor Registers, held in the Public Records Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI) at BG 1/GA/1 (3398 and 4317). In the first entry, she was described as a ‘dirty’ single 16 year old Roman Catholic female residing in Crumlin who entered the workhouse 30 September 1847, and left six months later, 27 March 1848. The second entry was the same, except that she was now described as a 21 year old servant who entered 6 April 1848 and left two months later, 25 May 1848. She was on her way to Plymouth to join the Earl Grey.

Catherine ‘married Charles Brown 13 July 1849 at St Andrew’s Presbyterian church, in Sydney, the Reverend John McGarvie officiating. The couple had twelve children, seven of whom survived infancy. Charles was a mariner but in 1854-5 became a goldminer in Avoca, Maryborough, Adelaide Lead, and Elphinstone, Victoria. The family moved to Echuca c. 1869 where Charles was a sawyer and carpenter. Catherine died 12 April 1906, exactly one year after her husband’. That looks as if it should be ‘eleven years’.

I’m sure Catherine would be pleased at being part of the history tour at Echuca.

My best wishes for the commemoration at Burgoyne Reserve, Williamstown commencing 3 p.m. on the 19th November. Here’s to everyone looking forward…to helping those in need…in memory of the Irish orphan ‘girls’.

An incomplete key to the contents of this blog is at http://wp.me/p4SlVj-oE

And just a reminder, after the comments on each blogpost there is a search box to help you navigate my blog.

There is plenty more from the Public Record Office Victoria at http://wiki.prov.vic.gov.au/index.php/Irish_Famine_Orphan_Immigration

You must be logged in to post a comment.