IRISH FAMINE WOMEN; a challenge or three+

Some people may have read the centre-piece of this post already. It is the talk I gave at the International Irish Famine commemoration in Sydney in 2013. Tinteán published an edited version sometime later. https://tintean.org.au/2014/03/06/irish-famine-women-a-challenge-or-three/

Today, I want to ask other labourers in the vineyard if they would take up some of my ‘challenges’. Is it true that Van Diemen’s Land bore the brunt of Ireland’s Famine misery? What do we know about the 4-5,000 single Irish women who arrived in South Australia c. 1855-56? Who were they? Where in Ireland did they come from? What happened to them? Over fifty years ago Cherry Parkin included them in her Honours thesis. As far as I know little has been done since.

There are no pretty or informative illustrations in this post. I’ve omitted them because i wanted to emphasize the importance of ‘words’. I hope you will ponder them. Note, too, there is one more example added to the end of my talk. I hope it tells you why i think this is important.

page 1 Irish Famine Women; a challenge or three

a chairde

Sul a gcuirfidh mé tús leis an léach seo, ba maith liom a chur in iúl an meas mór atá agam ar muintir na Cadigal don náisiún Eora, agus na shinsear a thánaig rompu a bhí i bhfeighil an dúthaigh seo. (Thank you Tom and Sinead and Síle)

One of the most striking achievements in Irish scholarship during the last eighteen years or so is the sheer range and depth of works on the Great Irish Famine. After years of relative neglect the sesquicentenary of that tragic event seems to have opened the scholarly floodgates. Yet surprisingly, there seems to be no major study of women during the famine. It’s as if a big piece of the jigsaw is missing. There are a number of excellent small pieces but no comprehensive study of Irish Famine women. An exemplary work, the closest yet to what I have in mind, is in fact a work in comparative literature; Margaret Kelleher’s The Feminization of Famine: Expressions of the inexpressible.(1997)

Professor Kelleher claims that “where the individual spectacle of a hungry body is created, this occurs predominantly (tho’ not exclusively) through images of women” [8]. [or Lysaght, 99] Think about that for a moment. If I say “Famine” to you, what mental image comes to mind?…..

For me, it’s an image of Sudanese and Somali women who appeared on our television screens last year. Victims of famine and drought, those women decided to take their hungry and sick children and walk for miles and miles in search of help.

It is an image that is echoed in the very moving stream of consciousness essay by Connell Foley at the end of that brilliant Atlas of the Great Irish Famine, [Cork Up, 2012, p. 678]

…and if you are a woman subsistence farmer in a remote part of the congo

or niger and you have five extra mouths to feed because your brother died

2 of hiv and you are looking at the sky and you are looking at your land

and you are calculating if there will be too little rain too late or too much

so that your basic crop will be ruined and you do not know how you will feed

your children or pay for some medicines but you get up every day

and you do what you can… [Beckett] You must go on…I can’t go on…I’ll go on.

And for the Irish Famine, it’s James Mahony’s London Illustrated News images of women. You probably know “A Woman Begging at Clonakilty”, for money to bury her dead child (Feb ’47), or “Bridget O’Donnell and her children” recently evicted from their holding near Kilrush. (Dec. ’49).

Yet looking thru/over my own research notes, what struck me is not women’s victimisation –but their agency, their stoicism and determination in the face of catastrophe –and the variety of their coping strategies. Women were the leaders in workhouse riots and protests in Cork, Limerick and Tipperary [BGMB records] asserting their entitlement to better treatment and better food. In 1848, 600 women rose en masse in Cork workhouse and attacked the visiting Poor Law Inspector, “having armed themselves with stones, tins and bottles”. In Nenagh, women were the leading characters…dashing saucepans, tins and pints of stirabout to the ground and smashing windows”. In Limerick, [in April 1849,] there was a riot of women screaming and throwing pints of ale at workhouse officers. These women were probably in the second of Professor Lawrence Geary ‘s three famine phases, the protracted period of “resistance’ which came after the initial “Alarm” phase and before the final phase he calls “Exhaustion”. The second phase, according to Professor Geary, saw the slow disappearance of community generosity and focus shifting away from ‘family’ to personal survival.[Mike Murphy lecture]

Women have always been given due/proper attention by historical demographers. Women’s age at marriage, their marital fertility rate and their mortality rate are crucial to any study of famine demography.

Of particular interest here is that more men than women perished during the famine. Women had what Kate McIntyre calls “a female mortality advantage”. An interesting twist to this is David Fitzpatrick’s suggestion, that –since women were in effect the principal guardians of comfort and succour, the primary suppliers of care and affection, they became the holders of the only entitlement, love, that may have been inflated by famine [67]. The mere thought of trying to examine the history of affection during the famine will no doubt be the stuff of nightmares for traditional historians.

If the evidence collected by the Irish Folklore Commission is to be valued,— [there is some debate about the reliability of that evidence, since it was collected long after the event itself. However, it’s too easy to dismiss/Nonetheless, I think we should learn to appreciate the skills of oral historians and the sophisticated ways they assess their source material. Such evidence can tell us something of what it was like to have been there. [O’Grada, Black ’47](Why were women in the oral tradition perceived as suffering the worst of consequences?) ] If the folklore evidence is to believed, women during the famine had a good reputation as providers of charity. The renowned Peig Sayers recounted to the Commissioners the story of a Kerry woman, Bridie Shehan, who tied her dead daughter to her back with ropes, and carried her to the local graveyard where two men helped her bury her daughter. When Bridie made her way back home, her neighbour, Nora Landers, called her in and gave her seven of her own precious seed potatoes. [ O’Grada’s Black ’47, 200-01]

A female outsider, an American visitor, Asenath Nicholson, a widow, who wrote about her travels through Ireland, also has a well deserved reputation for charitable good works. It is from her that we learn of an Irish Famine woman’s task of closing the door on her family’s grave. If I may quote from her work, (Annals of the Famine in Ireland)

A cabin was seen closed one day…when a man had the curiosity

to open it, and in a dark corner he found a family of the father, mother

4 and two children, lying in close compact. The father was considerably

decomposed; the mother, it appeared, had died last, and probably

fastened the door, which was always the custom when all hope

was extinguished, to get in to the darkest corner and die, where passers- by could not see them.

Such family scenes were quite common, and the cabin was generally pulled down upon them for a grave.[ Kelleher, 85]

Clearly then women were very much present in famine times. They were there in the workhouse [in Limerick, Cork, Nenagh (or wherever,)] rioting against their treatment and poor quality food. They were there inside the cottier’s cottage, their domestic domain, when the pile of potatoes on the table grew smaller and smaller and decisions had to be taken as to who got what, and how much. They were there around the family hearth when the decision was made to send their sons and daughters abroad, or to decide if the whole family should emigrate. And women were most likely there, at the very end when they could still close the door to their cottage, their family grave.

This then is our first challenge: a full blown study of Irish women’s role during the famine.

What part did women play in Irish society and economy? What work did they do in the fields, at sowing or at harvest time? Did they help dig ditches, gather sticks, dig turf, feed cattle, pigs and poultry or groom horses by lantern, late on a winter’s night? Was their work confined to a kitchen garden, washing, weaving, cooking, sweeping the yard and cleaning the house? How did all this differ from class to class or region to region before, during and after the Famine?

What exactly was women’s role in family life? Were women the chief providers of affection? What was their sense of moral value? Were they protectors and promoters of religious belief? Did they act as guardians of oral tradition and transmitters of language and culture? Did the Famine overturn traditional family structures and throw traditional mores into disarray? Did women have to find and procure food for themselves and their desperately hungry children by whatever means, travelling miles, begging, and stealing if needs be. [These are some of the questions that spring to my mind. I’m sure you will think of others.]

Without an understanding of women’s role, may I suggest to you, our knowledge of the famine will always remain incomplete?

Our second challenge then is a full-scale, comprehensive study of Irish-Australian Famine women. The important thing, as before, is that we view these women through the lens of the Famine.

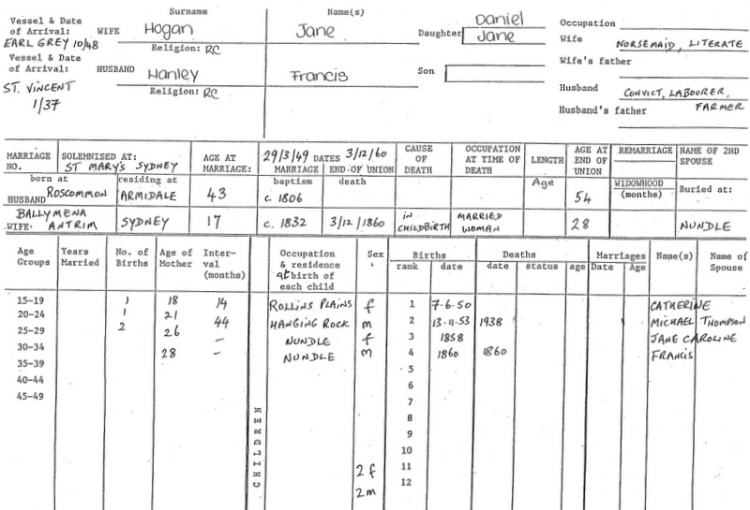

When I was preparing Barefoot & Pregnant? in the 1980s I was concerned about identifying people who knew an driochsheal, people who had first hand experience of the ‘bad life’, the ‘bitter time’ of the Famine. The young women who came here as part of the Earl Grey scheme were exactly what I was looking for. These young women obviously are essential to any study of Irish-Australian famine women.

But I think it is now time to cast the net more widely –to include, perhaps, some of the landlord assisted immigrants from the Monteagle estates in Limerick or the Shirley estate in Monaghan, for example– Or at least, the young women who came from workhouses in Clare and Cork to Hobart on the Beulah and Calcutta in 1851 –Or to Sydney, on the Lady Kennaway from Cork workhouses in 1854. These last, I’m sure you know, were the occasion of a fascinating political brouhaha here in NSW from the mid to late 1850s.

6

Let me give three examples to show what can be done—first, Irish female convicts transported to Tasmania, second, government assisted family migrants to NSW and Victoria, and thirdly, the immigration of c. 4-5000 Single females to South Australia in the 1850s.

At the beginning of the 1840s, about 1,000 Irish convicts were transported to Van Diemen’s Land each year. By the famine years, the annual intake had risen to 3,000. The transportation of female convicts, unlike that of males, did not stop during those years. “Tasmania thus bore the brunt of Irish famine misery ”, says Professor Richard Davis [9]. Not everyone would agree. Rena Lohan, a postgraduate student, in her study of Grangegorman, the women’s prison in Dublin, for example, found that most of the prisoners were already hardened criminals. Any link between Irish female convicts and the famine is tenuous, she argued. As always, the issue is complex and open to debate.

Were Irish judges more lenient in their sentencing during the famine? Knowing the difficult circumstances people were in, were they more prepared to accept as a defense, that crimes were committed “on grounds of want”? One such was the Exchequer Baron, John Richards who was willing to send convicts to Tasmania especially when he learned they had nowhere to go and would be without support when their prison term expired. Needless to say, not all judges and juries agreed on this matter. There was no consistent policy.

Did more women commit more crimes in order to be transported? Can we establish a strong link between the famine and the types of crimes they committed? Among the crimes recorded against the names of Irish women arriving in 1849 and 1850, for example, we note, “stealing a turkey’, ‘stealing a sheep’, ‘stealing a cow’, ‘stealing fowls’, ‘killed her child by a bandage, a little girl one month old’, ‘house burning’, which in itself carried a life sentence. Do we really need to distinguish between 7’intention’ and crimes born of desperation? Yet what of those women with criminal records stretching before the famine years?

Assuming we can identify female Famine convicts, what became of them in Tasmania? Were they different from other convicts? Were they less likely to re-offend? Were they less likely to be rebellious or to ‘resist’ the convict system, more likely to be ‘accommodationist’, and willing to accept their lot? Or did Australian conditions rather than their Irish famine background determine what became of them? The issues are complex are they not? Yet Tasmanian convict records are so rich it should be possible to answer many of these questions.

A second category of Irish-Australian famine women might include those who came here as part of their family’s emigration strategy. Richard Reid’s excellent work, Farewell my Children [Anchor, 2011], draws attention to the quite elaborate ways families in Ireland used Government assisted schemes to come to Australia during the famine years and the years immediately after. Manoeuvering the intricacies of bureaucratic regulations, filling out forms, collecting the required references from householders, from their local priest or magistrate or doctor, waiting for notification and arranging to join a ship in England, required skill, patience and detailed planning. Working the system, bending the rules, required a different kind of skill.

As family members discussed their emigration prospects around the hearth, in the domestic sphere, I am sure Irish women made their voice heard. One can surmise how influential women’s strength and determination and emotional clout was, in deciding how the family’s emigration strategy would be played out. Strikingly, Irish emigration to Australia in the 19th century was to achieve a gender balance. But in the famine, and years immediately following, many more women than men arrived as government assisted immigrants.

Dr Reid emphasises that it is a mistake to think of these young women, or the young 8sons and daughters in a family, being thrust into the unknown. They were often supported by an extensive and intricate network of family, friends and neighbours, sometimes stretching back to earlier convict days or bounty emigration schemes, sometimes needing a network to be established anew, set-up from scratch. We might ask did daughters play as important a role as sons in establishing these networks, not just for their own nuclear family but for their extended family and other members of their local community as well? Or were they less likely than men to nominate family and friends or manipulate Remittance regulations to their own advantage?

If I might illustrate the complications of this family emigration planning further, with an example form the work of an excellent family historian in Victoria, Anne Tosolini. I’ve used this example before in an article published in Descent in September 1999, [137].

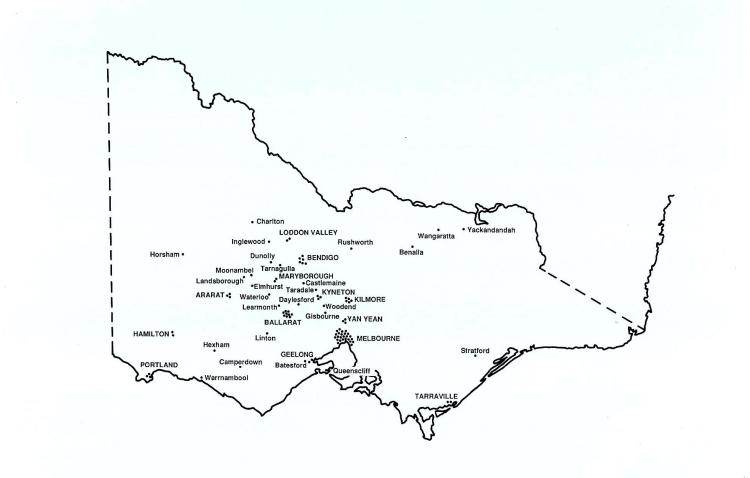

Siblings and cousins (sons and daughters) of the Frehan and Gorman families came here from the parish of Lorrha in Tipperary between 1849 and 1854, some of them to Port Jackson and some to Port Phillip. They were to regroup in Melbourne during those years, the men renting and purchasing properties in neighbouring streets in Richmond, close to people who had been their neighbours in Lorrha. The women, however, settled some distance away, in Geelong. When they married, and their husbands later selected land, they were scattered throughout different parts of Victoria, –their strong bonds of kinship thus becoming slowly and perhaps more easily weakened. Was there a ‘gendered’ difference in the colonial experience of the first generation of migrants? Did the women adapt more readily? Were women more willingly acculturated? Were they more independent in their choice of marriage partners? Was the regrouping of their family more likely to be ‘transitional’ than that of Irish men? These are questions about women’s role in their family emigration strategy that can, and still need to be addressed.

My third example of Irish-Australian Famine women is the circa 4-5 thousand young women who sailed into Port Adelaide in 1854, 1855 and 1856. Boatload after 9boatload of young single Irish females—by the Europa, the Grand Trianon, the Nashwauk, Aliquis and Admiral Boxer, for example,—came to South Australia in the mid 1850s as part of what I would call ‘ their flight from famine and its aftermath’. The Famine had opened the floodgates. Like the Earl Grey female orphans, they too might be considered famine refugees.

So many came in such a short time, so many were allegedly ill-suited to the work required of them, so many demanded food and accommodation in immigrant depots, and so many had been sent to Adelaide under false pretences (they had been told in London they could easily walk to Melbourne and Sydney) that South Australian government authorities established a government enquiry into what they called “Excessive Female Immigration”. Lucky for us they did so. In the minutes of evidence to their report we hear the voice of some of the young women themselves. The women called before the enquiry were asked why they came here. Their answers were what we would expect;–ambitious, independent, hopeful, banal.

[“February 15th 1855 Frances McDowell called in and examined, 32]

What induced you to come out here?—I do not know.

Had you received letters from friends? –I have no friends in Australia.

Did you think you would benefit yourself by coming to this Colony?–I was induced by the published statements to think that I might do well here.”

Some of these women were part of a network already here, and soon left South Australia to join their family and friends in Sydney and Melbourne. But my general impression is that the majority did not belong to such a network. ..Still, until there is an in-depth and thorough study of these women, our conclusions should remain tentative. This surely is a tempting research project for someone living in Adelaide.

Some excellent work has already been done on aspects of this so-called “Excessive” female immigration, –by Cherry Parkin, Eric Richards,Ann Herraman, Stephanie James, Marie Steiner to name a few. After acknowledging the initial troubles these young women had, –some walking 16 miles in the heat of the day, barefoot, to go to a situation, others returning to depot sunburnt, blistered, overworked and cast out after harvest was finished, some found crying, disappointed, despondent and depressed at their prospects—the view of most Australian writers is that these Irish women were generally well cared for and absorbed successfully into South Australian society. Areas of thickest Irish settlement …such as Paddy Gleeson’s Clare Valley were the first to accept and absorb them. The Seven Hills marriage registers demonstrate just how quickly they were accepted.

Other writers, outside Australia, are less upbeat. To quote from two, “The young women settled in badly and most left as soon as they could”. “Those sent into the outback as agricultural labourers barely survived”. (Akenson)

Who exactly were these young women? Which parts of Ireland did they come from? Where did their confidence, –or desperation, come from? What became of them? Were they being realistic in their expectations? Were they disillusioned? In fact, the same sort of questions may be asked of all of our Irish-Australian famine women, whether family emigrants, workhouse women, foundling orphans, convicts or convict families.

Is it possible to view them through the lens of their famine experience? Or at least try to view them from their own perspective? Look at their history through their own eyes, follow in their footsteps? This is my third challenge.

It’s not an easy thing to do. Finding out about the famine in our subject’s locality and even surmising the impact it might have had on our subject’s psyche, and subsequent life, are approaches we may need to take. It especially means our not accepting official sources at face value. They provide only a limited and slanted view of things –which is not that of the women themselves. Dig deeper. Read the sources “against the grain” [perhaps in the same manner as postcolonial Indian historians of the 1980s.] If necessary, rearrange the mental furniture we normally use in studying the past.

In the end, our sources may never allow us to get ‘inside the head’ of individual women. We may never get close enough to know them ‘in the round’–except perhaps through intelligent creative fiction. Which is why I’m very much looking forward to reading Evelyn Conlon’s Not the same sky [Wakefield Press, 2013]which is being launched later this afternoon.

Finally, our challenge is also about taking care with the language we use. Language is a loaded gun. If I may explain this by means of a few phrases, [–‘the Atlantic slave trade‘, the ‘Holocaust‘ and ‘pauper immigration‘.]

My first full-paid university appointment in the 1960s was in the West Indies. For me, a phrase such as “the Atlantic Slave trade” is a Pandora’s box, full of memories and meanings. But at its core is the 12 million people bought and sold like chattel, bought and sold like pieces of farm machinery or livestock, people denied their humanity.

One of the last courses I taught at Macquarie University before I retired included the Holocaust, the industrial mass murder of 6 million Jewish people. It was a subject that troubled me greatly. I found myself insisting upon saying Jewish people as a means of recognising the victims’ humanity. Without that recognition of our common humanity, it can happen again and again, as it did in Cambodia, in Rwanda and in the former Yugoslavia.

Even a seemingly innocuous/straightforward phrase such as “pauper immigration”, [still current in some quarters when writing about the Earl Grey famine orphans,] –has different layers of meaning. It carries a class interpretation. It implies that some immigrants are of less value than others, and hence, as human beings. Many of the young famine orphan girls who came here were bilingual, especially those from the west of Ireland. They spoke both Irish and English. The Irish word “bochtán” –‘poor person’– contains within it recognition of the poor person’s humanity in a way that the phrase, “pauper immigration” [Madgwick, chpt.X] does not. As those young women accommodated themselves to their new Australian circumstances they lost that language, and that world view; they lost that way of looking at the world. [There is a v. interesting essay, on this very subject by Mairead Nic Craith, Legacy and Loss, towards the end of that brilliant work, Atlas of the Great Irish Famine. p.580]

Today, I wish to add a third phrase, “the Irish potato famine” which is gaining currency these days. It is a phrase which many Irish people find insulting. Why is that? What’s wrong with those words?

Sure, failure of the potato crop is a very important part of what happened but as I said in post no.4 http://wp.me/p4SlVj-3I

famine is always about more than shortage of food and starvation. In that post I mentioned the work of Amartya Sen. Do search for him on google and for his colleague with whom he wrote about famine and poverty, Jean Drèze. I see one can even download the whole of Sen’s Poverty and Famines: an essay on entitlements and deprivation from more than one place. Even if you do not agree with his theory of entitlements applied to the Irish case you will realize how complex famines are. Poverty, over-crowding, a vicious land system, poor housing, underemployment, hoarding, thieving, price gouging, gombeen men, ‘culpable’ neglect on the part of government, the quarter acre clause, betrayal of one’s neighbours, and the unstoppable march of disease, are all in the mix. A phrase such as ‘the Irish potato famine’ misdirects our attention and fails to understand the complexities involved. “The Irish Potato Famine”–no; “The Great Irish Famine”–yes.

Let me put this another way. I’ll use the final words of David Nally in his Human Encumbrances.

“How are catastrophic famines to be prevented? One possible answer is provided by those who resisted famine policies in the 1840s: stop creating them”. (231)

Do please think about the words you want to use before uttering them.

Is minic a ghearr teanga duine a scornach (it’s often a person’s tongue/language cuts his throat)

My thanks to Tom Power, and Tom and Sinead McCloughlin for this saying.

Careful as you go. Mind your language.

Trevor McClaughlin 24 August 2013

A funeral in Old Chapel Lane Skibbereen

A funeral in Old Chapel Lane Skibbereen

You must be logged in to post a comment.