Anáil a tharraingt; a few more ‘monumental’ breaths

Following what was said at the beginning of the last post, here are a few more brief orphan stories for your delectation, and i hope delight.

But first a reminder of the SEARCH facility that appears after the comments to each post. I noticed, was it on the ‘Ireland Reaching Out The Earl Grey Female Orphans Australia’ facebook page that someone was interested in Rebecca Orr? So I typed Rebecca’s name into the search box and hit ‘search’.

Four different posts supposedly mention her somewhere. I tried the first and fourth item. The last one was a lengthy piece but I could not find any mention of her there. My eyesight? Or perhaps the system is not foolproof. It doesn’t seem to pick up everything that’s in picture form. The first item was a very different matter. It contained Rebecca’s family reconstitution form.

The search facility works haltingly for other subjects too. At best, it serves as an embryonic index. You might, for instance, look for ‘domestic violence’, or ‘Thomas Arbuthnot‘ or ‘Belfast Girls’ or…. I suppose like any index one gets most from it by being flexible, creative, and willing to explore. Try ‘Mary Coghlan’ after ‘domestic violence’, for example, or make sure you click on ‘older posts’ if you search for ‘Thomas Arbuthnot’. [Had a little trouble with that screenshot so have removed it.]

——————————————————————————————————————

Let me return to our ‘monumental’ breaths, and please, allow me to try something different this time, viz. include in this post some of the stories sent to me by orphan descendants when pre-2010 I and Jennifer Bainbridge were looking after the first version of www.irishfaminememorial.org

You may need to revisit this post, and just take one of these ‘histories’ at a time.

I’ve recently ‘recovered’ some stories on my computer, mislaid because of my cheapskate system of storing files.

My motive in uploading them now is to help keep Tom Power’s vision alive, and to allow readers to update, revise, improve, challenge, question the accuracy of, ask questions about, what is presented. Don’t be afraid to participate. I’ve often wondered how easy it is to establish a link to the young women who went to Victoria and South Australia, for instance. My own first question is usually “how do you know that? What is the evidence?” Regrettably I have lost touch with some of the people who sent me their story. Others I have not. Let’s see how this goes. Much of what is here made its way to the database in an abbreviated form www.irishfaminememorial.org

You may like to check there yourself. What do you think are the problems related to adding something to the database? It would be wise to err on the side of caution, would it not? Maybe Perry would be willing to tell us what yardstick she uses to add, or adjust entries to the database?

The first orphan story comes from Margaret Kirby in Victoria. Here was someone very excited by her discovery of maybe having an Irish famine orphan in her family. Can you identify with that? Alas, I do not know what became of the photographs she mentions. Maybe they are still buried somewhere in my computer. Here is Margaret’s email.

MARY McCREEDY from Galway per Derwent

<

I am much amazed. This is why. What Mary McCreedy told her children and grandchildren was that her father William McCreedy, a bootmaker from a town somewhere in Tipperary County (the family thought Nenagh) died. Her mother Elizabeth (nee Seymour) married a man that Mary McCreedy disliked intensely. It was decided- it was reported to her descendants- that Mary should go to America and marry a nice Irish boy who they knew who had already emigrated there. Mary then went to the docks, so the story goes, to get on the boat to sail to America. But when she got there she ran into some lovely friends who were going to Australia, so she got on the boat to Australia instead. At 15. With no further plans. We all understood that our ancestress was a formidable fire-breathing super-heroine. And that’s all we knew about her pre-antipodean life.

This is what happened today. I found the Immigration record for Mary McCreedy on Ancestry.com arriving on the Derwent in February 1850. Out of curiosity I thought I would find out who else was on the boat hoping to find some clues about her “friends”. I found out that every passenger was a girl aged between about 14 and 19 years old. “There’s got to be a tale in this”, I thought. So I googled Derwent 1850 Geelong, girls 14-19 and this web-site came up Irish Famine Memorial web-site. And there in the passenger lists was my Mary McCreedy, 15, Roman Catholic- so far so good- but from Newtonstuart, Galway?! Obviously somehow Mary McCreedy found herself in a poor house in Galway. How? Was she ever from Tipperary at all? Was her father a bootmaker- was her name even Mary McCreedy? If not she kept up that charade through two marriages in which she stated her father was William McCreedy bootmaker and her mother Elizabeth Seymour and that she came from County Tipperary.

I thought, “Maybe this is not my Mary?” But everything else sort of fits. Mary McCreedy married Henry Archer Baker in 1855 at St James in Melbourne which was both Catholic and Anglican in the one church, even though they lived in Castlemaine. She had been a housemaid. He had just lost his wife in childbirth. Maybe Mary had even helped his wife Sarah with the birth. Maybe Mary was pregnant. Maybe it was an alliance brought on by his grief and her loneliness. Anyway they married, moved from Castlemaine to Ballarat and about four years later he abandoned her with two small children Elizabeth and William.

So, we never knew exactly what year she arrived, nor did we know how she ended up in Castlemaine with Henry Archer Baker. It seems I can now account for at least two of the intervening years. According to this web-site Mary was employed by one William Ashby in Little Londsdale St. Paid 6 pounds for two years apprenticeship. Apprenticeship in what though? I found 2 William Ashbys in a 1847 list one who was a “dealer” and one who was a “carter” . Neither of these were in Little Londsdale. We do know that in her later life Mary ran a shop in Ballarat. Don’t know what kind of shop- but perhaps she ended up putting that apprenticeship to good use. Photos of her daughters, my grandmother and great aunt show them dressed in very expensive looking clothes.

By about 1861 Mary McCreedy had taken up with Henry Outridge, my great grandfather. Henry was born in Tasmania, the son of a free settling Blacksmith, John Alfred Outridge and a convict called Jane Phillips. Henry and Mary had 6 children. Alfred died in less than a year. Henry Joseph, Ellen Mary Clarice, Jane Josephine, Mary Clarence and Margaret Josephine. Henry Joseph married Hannah Rutherford and had four children before moving to the WA goldfields in Kalgoorlie where they had another. One son, Tom, was the first winner of the Sandover medal- the most prestigious WA football honour. He was named in the team of the century (20th). Henry his dad managed mines and seems to have been pretty successful. Ellen (Nell) married a Mr Baird but had no children. Jane married James Ryan and had 6 children. Mary Clarice married Daniel Jamouneau and had two girls. Margaret the youngest was my grandmother. She was born in 1878. A year later Henry Outridge married Mary McCreedy. For her whole life my grandmother lied about her date of birth. This covered the fact that she was technically born a bastard. Henry Archer Baker must have been unheard of for the requisite 7 years, so that the marriage could be declared null and void and therefore she was free to marry Henry.

But after all those years together, married life for Mary and Henry didn’t work out. The story goes that she threw Henry out of her house, cursed him to a terrible life, told him never to come back, and refused to hear his name again for the rest of her life. We think he died in the Ballarat hospital about 1896. Mary McCreedy lived in Ballarat for most of her life except for a period after my grandparents married and started having children. She was living with them- Margaret Outridge and John Joseph Kirby in Carlton in Melbourne when my grandmother was pregnant with my father in 1923. Mary McCreedy died only weeks before my father was born. She must have been living with them for some time because apparently she used to talk with my uncle Jack in Gaelic- and he could speak childish Gaelic fluently. My aunt the last surviving member of my dad’s family who could remember Mary McCreedy only died in 2007. Mary McCreedy was buried in Ballarat “new” cemetery in a grave with her mother in law Jane Phillips, a sister in law and many young family members who did not reach adulthood including her first child Alfred.

Undoubtedly, when she arrived at first in Castlemaine and then Ballarat, at the very heat of the goldrush, she would have lived in tent cities, with few if any niceties of life. But Mary McCreedy was evidently a survivor, a force to be reckoned with, undauntable. I was already proud to say her blood flowed through my veins.

Today, I have made a series of discoveries that have shed a whole new light upon this woman who clearly hid a grand chunk of her own story. It seems like many of the orphans experienced shame, or were judged harshly. Perhaps something of this lies at the heart of Henry Archer Baker’s abandonment. But then, from all the bits about her it is clear that this was not a woman to be crossed, least of all by a man, and doubtlessly few men of the times would take kindly to such a single minded soul. It’s all speculation. But now I have a bit of research to do. Galway? Workhouses?

I would love to know how this web-site has the information regarding the apprenticeships etc… What else can I find out? Is there more detailed information available about the workhouses? Were records kept in them of the girls’ origins and families? Who do I need to contact for the next step in this dramatic new line of enquiry?

Thank you thank you thank you for this web-site and the collation of all the material. I was in Sydney not so long ago and I saw that memorial! I had no idea what it was about but I liked a lot about it. The evocative objects, the tables, the photographs, the names. I did not realize that I was directly and deeply connected with this same story. The story of the Irish Famine and the orphan girls.

Wow.

The photos I have attached; The single Photo is of Mary McCreedy, clearly in alter life. The photo of the group is of Henry Outridge junior with family members at the mine he was managing in Ballarat shortly before his departure to WA. My granmother is the woman in white on the far right looking elegant. I suspect Mary McCreedy is the short woman in the photo holding the folded up white parasol. She is standing next to Henry on his left.

Thank you again, with great heart and real amazement,

Margaret Kirby>>

Here’s a very useful link from the Public Record Office Victoria especially for the Port Phillip arrivals. Happy hunting.

http://wiki.prov.vic.gov.au/index.php/Irish_Famine_Orphan_Immigration

Readers may also wish to visit Chris Goopy’s wonderful http://irishgraves.blogspot.com.au/

I took this pic c. 1991 when i visited the cemetery in Gordon in Victoria. I bet Chris has it somewhere on her blogspot.

a striking memorial at Gordon cemetery, near Ballarat

———————————————————————–

This next little ‘breath’ is from an orphan descendant who returned to Ireland to live. I wonder is she still in West Cork.

JOHANNA (HANNAH) MAHONEY from Cork per Maria

http://www.millstreet.ie/blog/about-2

<th March arriving in Sydney 1st August 1850 under the Earl Grey Scheme for Irish Famine Orphans.

The next record of Hannah is the birth of her son John Mahoney 28th July 1856 at Ballarat, illegitimate, mother unmarried (registration no.8388) Hannah Mahoney of Millstreet, Cork, Ireland.

Victoria Pioneer Index lists a daughter Hannah born in Ballarat West in 1859.

In 1861 on 28th August a daughter Charlotte Mahoney (my greatgrandmother) illegitimate, mother unmarried (ref.20053).

According to her death certificate Hannah spent four years in Victoria and forty-eight years in New South Wales.

A daughter Dinah (later recorded as Clara.D) was born about 1864 but no record of the birth.

New South Wales Births Deaths and Marriages then records:

12866/1867 Mary Williams

15011/1869 David Williams

14812/1872 George Williams

In 1874 Hannah and John Williams marry on 3rd June at Newcastle Roman Catholic Guild Hall

(N.S.W ref.1874/003273). Witnesses B.P.Stokes and Bridget Bourke. No details on the certificate other than names, occupation, conjugal status and usual place of residence as Waratah. Further enquiry with City Region catholic Centre in Newcastle provided the following information:

John Williams a miner age 57, born in Carmathenshire, South Wales, his parents were David Williams, a labourer and Mary Davis.

Hannah Mahoney was a housekeeper, age 40, born Millstreet, Cork, Ireland. Her parents were Daniel Mahoney, a shoemaker, and Catherine Sheehan.

Officiating Priest was Father James Ryan at St Mary’s Parish, Newcastle, N.S.W.

John Williams died of Influenza, Acute Pneumonia on 21st July 1894 at Gipp Street, Carrington age 72 years, parents unknown. Informant George Williams his youngest son. Children of the marriage:

John 38

Hannah 36

Charlotte 34 (my greatgrandmother)

Dinah 30

Mary 27

David 25

George 22

One male deceased

Hannah Williams died of Cerebral Haemorrhage having been in a coma for four days,on 21st July 1905 at Laman Street, Newcastle, age 73 years. Informant George, her son of Laman Street. Her parents stated as John Mahoney, bootmaker mother unknown. Birthplace Cork. States they were married in Ballarat 21 years ago. (Possibly an earlier non catholic marriage ceremony)

Children of the marriage:

John 50

Hannah 48

Clara.D 40

Mary 38

David 36

George 34

Living

1 male, 1 female deceased

Both Hannah and John were buried in Sandgate Cemetery (Church of England). The headstone is no longer there but the name Williams is inscribed on the concrete kerbing.

I was born and raised in New Zealand but have lived in West Cork, Ireland since 1993, about 30 miles from Millstreet where my great great grandmother left in 1850. I like to think a little bit of Hannah has come home

————————————————————————————

This next ‘herstory’ was sent by Fiona Cole. If I remember correctly Fiona discovered another member of her family arrived by the William Stewart. That vessel along with the Mahomet Shah and the Subraon brought a small number of ‘orphans’ as a sleight- of-hand trial for the larger official Earl Grey scheme. Nope, that turned out to be not the same Fiona.

Mary Jane Magnar (aka Mary McGuire) from Tipperary per Pemberton

<<(Born: c1832 – Died: 1 December 1882)

Mary Jane McGuire (Magnar) was born c.1837 to parents Thomas Magnar and Johanna Frein, Tipperary, county Tipperary, Ireland.1Mary Jane came to Australia on the “Pemberton” as a Female Orphan at the age of 17. On the register, she is initially listed as Mary McGuire, with the name Magner written beside the first surname in smaller print. Mary Magnar was received into the Depot on 26 May, 1849 by “A. Cunningham” of “Kinlochewe,” a village just outside of Melbourne on the old Sydney Road, near Donnybrook in the district of Merriang in the electorate of Whittlesea. She was licensed out (hired) to the Cunningham’s for a period of six months on the 31st of May, 1849, at the rate of ₤10 -0-0. Her usual profession is cited as being a ‘child’s maid.’2Andrew Cunningham held a freehold in the district of Merriang at the time he enrolled on the Australian Electoral Roll 1 May, 1849 and on the 1851 roll held a freehold in the Plenty Ranges in the district of North Bourke. In the Victorian elections of 1856, he is listed as a freeholder at Merriang, Whittlesea Division. This is believed to the same ‘A. Cunningham’ who received Mary Jane Magnar from the Port of Melbourne. A Cunningham is listed in the Banniere’s directory of 1856 as a farmer at Whittelsea3. It is likely therefore, that Mary Jane was employed as a farm maid and worked on the property north of Melbourne from 1849 until she left the Cunningham’s employment.

Andrew Cunningham, born around 1811 would have been approximately 38 years of age when Mary Jane Magnar came to work for him and his wife, Martha (nee McDougall) at Kinlochewe. Although Andrew and Martha Cunningham had a son (Charles Andrew) born in 1851 at Merriang (who died in 1860 (aged 10)) it is possible that Mary Jane was the child’s maid for a period of time, but it seems more likely that she worked on the farm as a domestic.

In 1861, the Cunningham’s had another child, Martha Eliza, but by this time, Mary Jane Magnar had well and truly left their employ.

By 1856 Mary Jane Magnar left the Whittlesea district and moved to Beechworth, possibly in the company of friends made while on board the Pemberton. The 1856 marriage register showing Mary Jane’s marriage to Richard Young Trotter also shows that the next marriage to be performed was for that of her shipmate, Mary Collins.4The marriages were performed by Rev John C Symons, an evangelical minister who spent several years ministering on convict ships and throughout the gold fields, trying to bring God to the lives of the poor.

Mary Jane and Richard Young Trotter lived at Beechworth and had at one child5, Mary Jane Youngtrotter (who would go on to become Mary Jane Harrison and then Mary Jane Gould).

Mary Jane’s husband, Richard worked as a carrier and a teamster during their short marriage. He died by accidental drowning in the Mitta Mitta River at Morse’s Station on 5 November 1857.6 Surprisingly, there was no inquest into his death, Richard and Mary Jane Youngtrotter appear to have been living at Yackandandah at this time, but after his death, Mary Jane appears to have returned to live in Beechworth.

Mary Jane Youngtrotter registered the birth of three children (1858, 1862 and 1865) after the death of her husband in 1857. None of these children survived more than a few days. The first of these children, Thomas, was the subject of an inquest and Mary Jane was held accountable for Manslaughter by Neglect. The charges were dropped and the coroner found that she had no case to answer. Witnesses were brought before the court both for and against Mary Jane.

For the prosecution, a witness by the name of William Hughes testifies that Mary Jane was frequently drunk and ‘could not even hold a glass of brandy without spilling it.’7In her defence, Thomas Conway, apparently the father of the child and her civil union partner claimed that while Mary Jane was known to drink, she was not incapable of looking after the child, nor was she drunk the night the child died.8 Furthermore, he testified that when he returned home on the night the child died, he found Mary Jane sitting on a stool, crying. He claims that she said to him “Thomas, my child is dying.” at which point, he left to find the doctor to help the child, but by the time they returned it was too late.9Mary Jane Youngtrotter appears to have lived a somewhat sad life after the death of her third baby, as she was incarcerated from 1865 for larceny10 and vagrancy11. It appears that Thomas Conway either died or did not stay with her after this point as he does not feature as a near relative or next of kin on her admittance records to the Beechworth Asylum.

Mary Jane Youngtrotter’s only surviving child (Mary Jane Youngtrotter (later Harrison and then Gould) was admitted as of the state to the Industrial School in 1865 and then assigned to the Brown family of Curyo Station in 1868.

On 12 August, 1871 Mary Jane Youngtrotter was admitted to the Beechworth Lunatic Asylum and released a month later on 26 September 1871.12On Thursday 6 September 1873 Mary Jane Youngtrotter appeared before Judge Bowman at the Beechworth General Sessions. She was charged with Attempted Suicide. The prosecutor told the judge that her crime was a misdemeanour and recommended no heavy penalty. The Judge ordered that she be released to enter into her own recognisance provided she pay a ₤20 surety (or as the Wodonga Herald claims, a ₤90 surety13) and a ₤50 fine to keep the peace for six months, or in default, one month’s imprisonment.14It appears that Mary Jane Youngtrotter could not afford the surety or the fine and was remanded at Beechworth Prison as this is listed on her subsequent admission to the Beechworth Asylum as her last known place of residence.15Mary Jane Youngtrotter was admitted to the Beechworth Asylum 2 October, 1873 (a month after her court appearance before Judge Bowen – the time prescribed by Bowen that she should serve in default of payment of the surety and fine) and she remained there until her death 1 December 1882.16Mary Jane Youngtrotter’s death certificate states that she died aged 45,17 however, her marriage certificate to Richard Youngtrotter, provides an alternative and more realistic date of birth, stating her age as 23 in 1856, making her 59 when she died.

Fredrick Western (Medical Superintendant) at Beechworth Asylum noted that Mary Jane Youngtrotter ‘suffered from delusinal [sic] insanity and delicate bodily health.’ and that 10 months before her death she was ‘somewhat feeble and unable to go about.’18 By the 20 November 1882, Mary Jane Youngtrotter was ‘rather ill and confined to bed.” By the 23 November she was transferred to the Hospital. She did not improve and gradually her health worsened until she died. Her death was reported to have taken place at 5.30am.19There are no case notes for Mary Jane Youngtrotter’s time while incarcerated at Beechworth Asylum – PROV holds female case books 1878 – 1912.

© Fiona Cole, 2005

1 Richard Youngtrotter and Mary Jane Magnar Marriage Certificate –

2 Shipping List – Pemberton, 14 May, 1849, pg 13 (PROV- Microfiche)

3PROV XXXXX

4Marriages solemnized in the District of Beechworth, 1856, nos 73 & 74

5 Richard Trotter Death Certificate

6 Ibid

7Thomas Young Trotter Inquest VPRS30/PO Unit 219 File NCR 2339

8Ibid

9Thomas Young Trotter Inquest VPRS30/PO Unit 219 File NCR 2339

10VPRS 516/P1 Central Register of Female Prisoners, Mary Jane Youngtrotter, Prison Reg. No 573, Vol 1, pg 573

11 Mary Jane Young Trotter – Industrial School Records VPRS 4527, Vol OS2, pg 147 (No 633)

12 VPRS 7446 P1 Alphabetical Lists of Patients in Asylums (VA 2863)

13The Wodonga Herald, Saturday 6 September 1873

14The Ovens and Murray Advertiser, Friday 5 September 1873

15 VPRS 7446 P1 Alphabetical Lists of Patients in Asylums (VA 2863)

16 Ibid

17Mary Jane Youngtrotter death certificate – Apppendix XX

18 Public Records Office Victoria (VPRS 24/P/0000 – Unit 446, 1882/1373).

19Ibid

https://www.prov.vic.gov.au/search_journey/select?keywords=Beechworth%20Asylum

————————————————

This next story is about one of the first arrivals. This one is from Neville Casey I believe.

Ann Jane Stewart from Tyrone per Earl Grey

<<Patrick CASEY (originally spelt ‘Keasey’, probably by an English clerk who was tone deaf!) arrived in Australia in 1829 as a 30 year old convict from on the vessel ‘Sophia’, having been sentenced to ‘life’ for stealing a fish which was drying on the window sill of a house in Naas, County Kildare. Little did he know that the house was that of the local magistrate – Ah, the luck of the Irish! He was sentenced at the assizes in Naas, County Kildare, on 24 March, 1828 before the Right Honourable Justice Lord Plunkett.

By 1838 his wife Eliza (nee TREVERS), with their son Mathias (Matthew – aged 12) had arrived on the ship ‘Diana’, as part of the scheme to reunify families of transported convicts. Patrick had applied for this around 1836 by writing to the Colonial Home Secretary. He was given a Conditional Pardon in 1844, and lived in the area known as Cooley’s Creek close to Morpeth, outside Maitland. Eliza and Patrick died on the 2nd January and 8th July in 1867 respectively, and both are buried at East Maitland cemetery.

My great-great grandmother Ann Jane (‘Aimie’) STEWART arrived on the ‘Earl Grey’ on the 6th October, 1848. Ann was born in County Tyrone, in 1831 to William STEWART, a carpenter, and Ann Catherine STEWART (nee MARGUS), both of whom died in the years just prior to coming to Australia as one of the original Irish famine orphans aged 16 years. Upon her arrival, she stayed at the Hyde Park Barracks briefly, before setting out to work for her employer in early 1849.

She was indentured to John STEWART, a veterinary surgeon of York St., and paid £10 for the first year. It remains unclear as to whether Mr. Stewart was related, but he was trained in Scotland, and was a well known equine veterinary surgeon, politician and supporter of Sir Henry Parkes’ position on many social issues. John Stewart moved his family to Keira Vale, near Wollongong, where he raised horses. He combined a horse bazaar with his work until 1852, when he relocated to Kiera Vale, near Wollongong, to provide a country upbringing for his young children. Active in local public life, he was a magistrate for a time, chairman of the Central Illawarra Municipal Council in 1860, a leader-writer for the Illawarra Mercury and a promoter of various social activities and charities. However, on 7 September 1849 Ann Stewart’s indentures were cancelled, she was paid out a sum of 18 shillings as the balance of her wages, and moved to the area of Bong Bong, a small town near Moss Vale, in the Southern Highlands of NSW.

She consequently met and married Matthew CASEY, the only son of Patrick and Eliza, at Berrima. The marriage took place in Berrima, and was performed by Father William McGinty in February 1850. Clearly, Matthew had moved from Morpeth to Bong Bong, although it remains unclear as to the reason. They moved from Bong Bong to the Shoalhaven district, where their daughter Elizabeth was born in Dunmore in November 1850, and Matthew worked as a farmer. In 1852 their second daughter Annie was born. In 1855 their first son Patrick was born, however no district for the birth was recorded.

Anne Jane Stewart

They again moved north to the Manning River area near Wingham on their way to Port MacQuarie between 1856 and 1858, where their second son Christopher was born in 1858, followed by Mathew in 1860. In 1863 they moved to Redbank, near Wauchope, inland from Port MacQuarie where their fourth son, Edward (my great grandfather), was born. In 1866 and 1868, Mary and Daniel were born. In 1867 Matthew went bankrupt, but Patrick had left his farm to his granddaughter Elizabeth, who had to wait until she was 21 years of age in 1871 to receive her inheritance. She was coerced by her family into selling the property to settle the bankruptcy debt. Matthew worked as a farmer, with his sons working as farmers and sawyers.

To add to their woes, in 1872 Matthew was arrested for cutting and wounding Mr. Gavin Miller in a knife fight by Snr. Constable Ryan of Port MacQuarie Police. He appeared in the Quarter Sessions of the Magistrates Court, on 19th March 1873, and was sentenced to 6 months gaol. Their youngest son, John, was born in 1875.

In total, they had 10 children, 9 of whom survived to adulthood, and had 73 grandchildren in total. Many remained in the area around Port MacQuarie and the Northern Rivers of NSW. Three of their sons, and their families, later moved to Queensland to work in the timber industry.

In their later years, Matthew and Ann moved to Gladstone, NSW, where they lived their later years. Ann died in Gladstone NSW on 20 March 1898 aged 62, and was buried at Frederickton cemetery on the following day. In early 1908 Matthew caught a steamer from Newcastle to Brisbane, to visit his grandson Patrick, but became ill with pneumonia and died in the Brisbane General Hospital on 15th July, 1908 and was buried in Toowong cemetery on 17th July 1908.

There exists very extensive family history and database to date, their being some 300-400 direct descendants still living, mostly in the SE Qld. and NSW Northern Rivers area; with over 1700+ family members known to date.>>

JULIA LOFTUS from Ballynare, County Mayo, per Panama

Here’s the story of Julia that appears on the West Australian Genealogical website below. Julia’s story is included here with the permission of her descendant Chris Loudon. Thanks heaps Chris. Fingers crossed that the links provided by Chris work for you.

http://membership.wags.org.au/membership-mainmenu-44/members-only/wags-tales/470-an

< Email Chris This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it

The Irish Famine had a devastating effect on the population of Ireland in the period 1845-1850. Approximately 1.5 million men, women and children died of starvation or disease in this period, and more that 2 million others fled from Ireland to avoid death by starvation.

Of those who departed, there were approximately 4,000 Orphan Girls given assisted passage to Australia between October 1848 to August 1850, under what was known as the Earl Grey Scheme. This article is about one of these Irish Orphan Girls.

Sydney was hot and sultry in the early hours of the morning on Saturday 12 January 1850, with dark clouds, lightening and heavy rain. At 8:30am the temperature was 64° F (18° C) and by 2:30pm had reached 76° F (24.5° C), the sky clearing in the afternoon with quite pleasant sea breezes.

The Panama, a barque of 458 tons under the command of Captain Thomas, dropped anchor at Sydney Cove on this Saturday having sailed from Plymouth on October 6 1849, and spent 97 days at sea without calling at any other port[1].

The passengers on the Panama consisted of … nine married couples, two children and 165 Irish Orphan girls.[2] They have been very fortunate during the voyage, not having had a single case of sickness of any contagious description[3] … They were no doubt looking forward to disembarking after their long sea voyage.

The Panama also carried an interesting mix of cargo, focused on tools for the land, tools for the homes of settlers, their drinking habits being well catered for, and news from London that a cholera epidemic appeared to be waning.

Francis L.J. MEREWETHER, the agent for immigration at Sydney, in a letter addressed to the Secretary General Earl GREY in London, dated 7 July, 1850 commented that:

…The Panama besides being a vessel of smaller tonnage than it is desirable to employ for the conveyance of Emigrants to this Colony, is, like most North American built ships, ill suited for the service, her tween decks being dank, dark and very imperfectly ventilated. She was a new ship but leaked through the voyage. On examination here, the leak, I understand proved to have been caused by two open boltholes, into which bolts had not been driven.

The tween decks were in a cleanly state on arrival and the arrangement made for the presentation of good order as well as for the health and comfort of the Emigrants, appear to have been satisfactorily carried out.

The Immigrants were in good health on their arrival and when individuals questioned in accordance with the practice of the Board of Inspection here, said they had no complaints to make regarding their treatment in any respect.

The Surgeon Superintendent, Mr. A. Wiseman performed his duties in an efficient manner. He reported that he received all requisite assistance from the Master and the Officers of the ship.

The Matron appeared to have performed her duties satisfactorily. The principal diseases reported by the Surgeon Superintendent were Tympanitis[4] and bowel complaints[5] …

Great Great Grandmother Julia LOFTUS remained on board the ship at anchorage for a further 6 days after the ship arrived along with numerous other Orphan Girls. She then spent an additional 3 days at the Sydney Orphans Depot.[6]Julia is recorded on the immigration records as Judith LOFTUS.[7] She was …a native of Ballynare[8], Castlebar Co. Mayo, parents Edward and Bridget Loftus both dead[9], R.C., neither read or write. State of bodily health, strength or usefulness; Poor. No relations in Colony. No Complaints….

The majority of the girls, who arrived on the Panama as part of the Earl Grey Migration scheme, were orphaned due to the conditions in Ireland during the Potato Famine.[10] Whatever the cause of being in the “Irish Poor Workhouses”, it was a massive move for these young girls. There was no doubt a sense of adventure mixed with trepidation in coming to start a new life full of uncertainty.

The Irish Orphan Girls were not always welcomed into the community with open arms, and the colonies were in uproar at the behavior of some of the girls. They were variously sent to indenture in the interior of the colony, some were taken advantage of, others turned to prostitution just to stay alive. The majority kept a low profile and had success in their new country, despite the hue and cry from the press of the day.

The Panama Orphan Girls were dispersed to their respective assignees; 92 girls engaged in Sydney, 67 sent to Wollongong, 11 to Maitland, 10 to Moreton Bay, and 2 to Bathurst.[11]We know from the records that Julia was one of those who went to the Wollongong Depot, and was engaged as a house servant at a wage of £8 for 12 months with board and lodging by one W. TURKINGTON of Dapto. Julia may have spent the next two years at Dapto, but was in Sydney some time prior to her marriage to John QUINN in May 1852.

Julia LOFTUS married John QUINN, a free settler, at St. John the Evangelist Roman Catholic Church at Campbelltown, NSW , on 17 May 1852.[12] Julia was 21yrs of age and John was 34yrs. Father John Paul ROCHE, the parish priest, celebrated the marriage.

We can only imagine the tears and joy, which Julia would have felt with all of the things happening in her life. Orphaned and probably lucky to be alive herself as a result of the Potato Famine in Ireland, shipped to New South Wales at age 19 to an unknown future, indentured to a farmer as a servant, and now married at age 21 to a man apx. 9 years her senior, all within a time frame of just over two years.

No doubt other influences led to Julia and John being together, one of which would have been their Roman Catholic Irish descendancy. Julia gave birth to their first child, Bridget, on 19 April 1853.

During the next 46 years, Julia experienced a lot more happiness and no doubt considerable pain also. She was to give birth to 13 children between 1852 and 1871, depending on which records are correct.[13]The death certificates for both Julia and John show that 9 children – Michael, Edward, John, Bridget, Anthony, Ellen, Julia, Thomas Patrick, and James Hugh, survived them, plus 4 males and 3 females deceased (no names shown). This gives us a total of 16 children, and complicates matters somewhat, as we have only 13 recorded births.

Julia QUINN/LOFTUS was no doubt one tough lady. We can only imagine the heartache associated with a harsh life on the land for a woman in the 1850-1870’s, not to mention the multiple deaths of infant children.

A lot of questions arise, few if any which we can answer, however it appears that Julia and John made a good go of their life together, remaining together until Julia’s death.

On February 17, 1899, the day before Julia QUINN died, a handwritten will was made out for her, apparently by one of her sons, as under:

Jamisontown, 17th Feb 1899. I Julia Quinn of Jamisontown Penrith in the Colony of New South Wales do hereby bequeath all my properties at Jamisontown with cottage furniture and effects to my son Edward Quinn.

Signed this day in the presence of the following witnesses.

T. Quinn. Julia Quinn.

J. Quinn. X. her mark.

A. Quinn. 17th Feb 1899.

Edward Quinn X. his mark.

Executor to the above will.

The three witnesses to the will were her sons, Thomas then 31 years of age, John 40, and Anthony 34, Edward was 42 at the time.

Julia QUINN (nee LOFTUS) passed away at Jamisontown NSW on February 18, 1899 at the age of 68, and an Obituary notice was printed in the Nepean Times soon after. She predeceased her husband by about three years. A similar notice appeared for John QUINN after his death.[14] Julia is buried at Jamisontown Cemetery near Penrith.

Letters of administration of the estate of Julia QUINN were granted to Edward QUINN, the sole beneficiary of the will on July 5, 1900.[15]This is a little perplexing as John QUINN, Julia’s husband, was still living at the time, although 81 years of age. However, this is explained by the cause of death shown on John’s death certificate as being senile decay; in all probability he would have been incapable of attending to the administration of Julia’s estate.

Edward was married to Elizabeth O’CARROLL in 1895. Edward died at Penrith in 1931 and Elizabeth in 1933 they had no children.

Photo of John and Julia QUINN taken circa 1870.

(Copy supplied to the author by Pat Curry; original held by Dr. Peter Quinn)

As can be seen from the photograph, neither Julia nor John appear to be particularly tall, and that Julia appears to be pregnant, as she would have been almost perpetually over the 20 years 1852 – 1871.

There were a number of sad incidents in Julia & John QUINN’s life, all in and around the farming area of Camden, Mulgoie Forest, Penrith and Jamisontown in NSW where Julia and John lived:

1858 – At age 27, two of her children were to die young and within days of each other, Bridget aged 5 years and John aged 22 months, both of “scarlatina” (scarlet fever)

1860-61 – age 29, another of her children died at a very young age, Anthony, aged 6-12 months.

1886 – Julia was to see her son Michael suffer with the loss of his first wife, Hannah (nee STAGGS) died on September 17, 1886, soon after the birth of their daughter Hannah, who also died 3 days later, there were 3 other children still living.

1886 – George and Mary STAGGS (apparently living at Penrith NSW, in 1886), the parents of Michael QUINN’s wife Hannah, raised all of Michael’s and their daughter Hannah’s remaining children; George John (6yrs), Michael James (4yrs) & Mary Jane QUINN (2yrs). Julia and John QUINN may have been unable to care for them, or the perhaps the best solution was for them to go to the STAGGS.

1891 – Julia QUINN nursed her daughter Mary Jane (married to William WILKINSON), after Mary Jane had given birth to son Anthony (b March 7, 1891), only to lose her to ‘Pleural Fever’ on March 17, 1891, 11 days after the birth.

1891 – After his mother’s death, Anthony WILKINSON was raised by his uncle and aunt, Anthony Joseph QUINN and wife Bridget (nee McMAHON) at their farm and orchard at Kurrajong NSW. Anthony QUINN was Mary Jane WILKINSON’s younger brother.

1899 – Julia QUINN was to lose another of her grandchildren through a tragic accidental drowning on February 10, shortly before her own death. This was William James WILKINSON (aged 19 or 20), the son of her daughter Mary Jane and William WILKINSON. William James was living with his brother John and sisters Julia and Mary Jane, all being cared for by Julia Jane and Esdras GIDDY at the time. This tragedy happened on “York Estate” (Penrith), owned by Mr A. JUDGE and was reported in the Nepean Times.

One of the people, who attended the accident scene and lent a hand in recovering the body of William James WILKINSON, was a Mr. E QUINN. This was no doubt Edward QUINN, Julia & John QUINN’s son, Mary Jane WILKINSON’s brother and an uncle of young William. Edward was obviously nearby, perhaps also staying with his sister Julia Jane and her husband Esdras GIDDY, or with his mother Julia QUINN. Edward was in the area attending to his sick mother Julia QUINN who was to pass away on February 18, 1899, only 8 days after the death of William James WILKINSON. Julia’s cause of death was a cerebral haemorrhage, which she had suffered 5 days before, and just 3 days after William’s tragic death.

The young girl who made the discovery of William WILKINSON’s drowning was Julia WILKINSON (b 1885), his younger sister, and daughter of Mary Jane WILKINSON, she was the granddaughter of Julia QUINN.

Julia QUINN (nee LOFTUS) made the best of her life in Australia, and contributed to the growth of her adopted country. She left the legacy of a large family of descendants all of whom are grateful to her having arrived in 1850.

Notes & Sources

General Notes

Information contained herein has been sourced from primary and secondary sources, including certificates, as well as through material supplied by numerous descendants of Julia and John, in particular Julia Haggerty who has been generous with details of her research.

Descendant family members with additional information, or corrections, are encouraged to contact the author. In particular we would love to receive copies of any photographs of Julia and John, and their children, to share with the wider family, with permission of course.

Sources

[1] The Sydney Herald, Saturday, January 12, 1850

See NLA Newspapers site for articles on the arrival of the PANAMA

[2] SRO NSW Reel 2461 Ref 4/4919 records 157 Female Orphans

[3] The Sydney Herald, Saturday, January 12, 1850

[4] Inflammation of the ear drum

[5] McClaughlin, Trevor – ‘Barefoot and Pregnant’ – Irish famine orphans in Australia’, Pub. The Genealogical Society of Victoria Inc. Trevor McClaughlin now has a wonderful blog presence (since 2014), go here for Trevo’s Irish Famine Orphans

[6] Originally Hyde Park Convict Barracks, now The Barracks Museum, Macquarie Street Sydney NSW – Julia LOFTUS’s name can be seen engraved on the (glass) Irish Famine Orphans Memorial Wall at the Barracks Museum . This memorial was part of the Gift to the Nation from the Irish Government to the Australian People in celebration of the Bi-Centennial of Federation. Two of our immediate family members (sisters Elsie and Norma), great granddaughters of Julia’s, attended the unveiling of the wall on 2nd September 1998 as guests of the Irish President Mary Mcaleese. There were also other extend family members attending this celebration.

[7] SRO NSW Reel 2461 Ref No 91 – see also ‘Barefoot and Pregnant’ – Register section pp88

[8] Probably Ballina (or possibly Ballinrobe) Mayo, as we can find no references to Ballynare in Mayo, and given the broad Irish accent it was possibly recorded incorrectly – See detail on the Ballina, Co.Mayo Workhouse here – On the birth certificate of Julia’s son James (1871), John Quinn (informant) states that Julia came from Crossmolina, near Ballina in County Mayo.

[9] Nothing is currently known of the circumstances of their lives or deaths; however the timing would suggest they were victims of the Potato Famine/s – See detail on the Great Famine in Mayo here

[10] Source: ‘Barefoot and Pregnant’ – For lists of orphan passengers on Panama, and other vessels under the “Earl Grey” scheme. Digitised copies of Immigrant Passenger Lists, for ships between 1838-1896 i.e. Immigrant Passenger Lists, including famine orphan ships, is now available online “Persons on Bounty Ships” at the State Records office of NSW website. Click here for the “Panama passenger list” , including Female Famine Orphans.

[11] SRO NSW ref 4/1149-1, reel no 2461 – Ship Surgeon Generals report on dispersal of the Panama passengers, and other records

[12] Marriage reference – SRO NSW Reel no 5039 BDM Vol 98 Fol 310 May 17, 1852

[13] SRO NSW microfiche Records and BDM records (var. refs), show births for 12 children and 3 deaths

[14] The Nepean Times, January 12, 1901 – Now available through the NLA Trove website – See Trove the “Nepean Times” – Copies of the newspaper are available at the Penrith City Library, NSW

[15] Probate Office of NSW – reference Will No 206 44/4, 5th July 1900 – Administration to Edward QUINN – sole beneficiary>>

Interested readers may like to visit Barbara Barclay’s website http://mayoorphangirls.weebly.com/

—————————————————————————————–

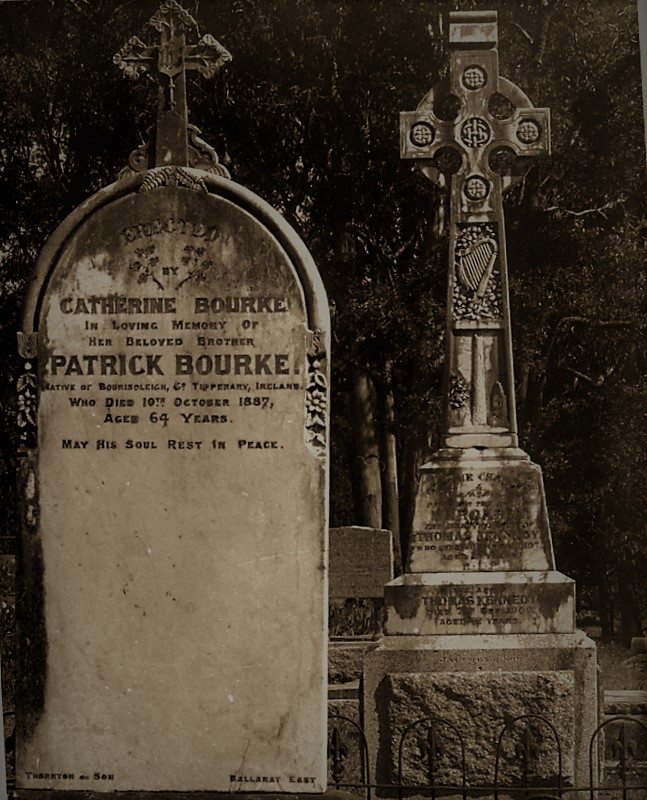

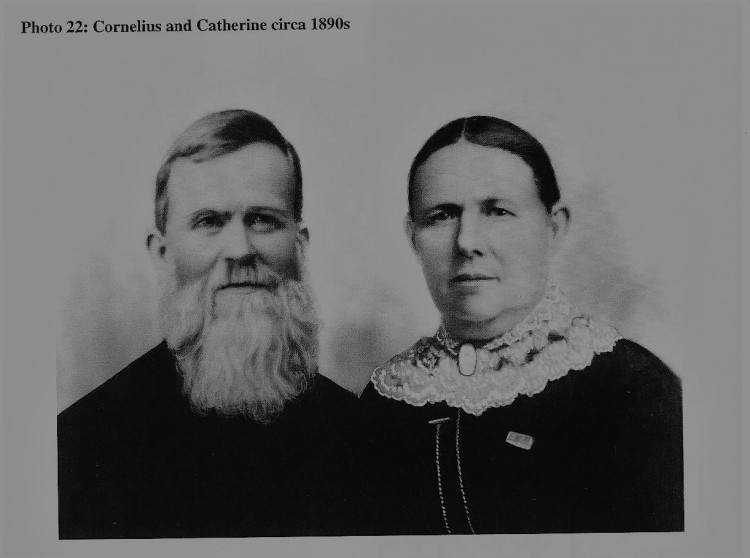

CATHERINE HART from Galway per Thomas Arbuthnot

Finally, the fascinating story of a Galway orphan based on the admirable work of Rex Kerrison and Anthea Bilson. You may know them from Barrie Dowdall and Síobhán Lynam’s television series Mná Díbeartha. What appears below is based on their well- researched and beautifully produced family history, Catherine and Cornelius Kerrison. Two Lives 1830’s-1903, Launceston, 2010 (isbn 978-0-9806788-2-6)

Have a close look at the family reconstitution chart I’ve compiled from Rex and Anthea’s book. Is there anything that strikes you as irregular?

There are a couple of things in particular; on the right hand side you will notice her first husband was a W. Pollard. She didn’t marry Cornelius until May 1883.

There are a couple of things in particular; on the right hand side you will notice her first husband was a W. Pollard. She didn’t marry Cornelius until May 1883.

From Rex and Anthea’s family history page 36

As always, check the database.

- <Hart

- First Name : Catherine

- Age on arrival : 17

- Native Place : Galway

- Parents : Mark & Ellen (both dead)

- Religion : Roman Catholic

- Ship name : Thomas Arbuthnot (Sydney 1850)

- Other : shipping: house servant, cannot read or write, no relatives in colony, sister Mary also on Thomas Arbuthnot; Empl as house servant by Samuel Hill, Gundagai, £7-8, 2 years. Im.Cor. 50/747 Yass; married 1) William Pollard, RC Gundagai 1851; marriage short-lived as she bore a son to Cornelius Kerrison in Bendigo in 1854; she had 11 children with Kerrison [free with family to VDL on Charles Kerr 1835] & married him in Launceston in 1883 witnessed by her sister, Mary Baker, nee Hart; visited Ireland alone in 1899; she died Beaconsfield, Tas, 1903, buried St Canice RC Glengarry, Tas; headstone with shamrocks & celtic cross.>>

Catherine and her younger sister Mary travelled with Surgeon Strutt and a hundred other young orphans from Sydney to Gundagai. Strutt’s diary recounting that journey is reproduced in C. Mongan and R. Reid’s ‘a decent set of girls’ The Irish Famine orphans of the Thomas Arbuthnot, Yass, 1996. (Perhaps your library has a copy? It’s well worth reading. Did the State Library of Victoria publish a copy, does anyone know?)

Catherine married William Pollard in October 1851 nineteen months after arriving in Gundagai. Was she there during the terrible flood of 1852? Or had she already fled with Cornelius Kerrison to the Victorian Goldfields? All that is known is that she and Cornelius had a son Stephen born in 1854 at Sailor’s Gully near Bendigo. (Kerrison and Bilson, p.15)

Anthea and Rex and their co-researchers unravelled the puzzle of Catherine’s life with great skill. Surprisingly, Catherine and Cornelius returned to Gundagai in 1857. Did Catherine wish to see her sister again, or seek a divorce from William Pollard? Whilst there she gave birth to Ellen, her third child. Ellen was registered as ‘illegitimate’, and registered three times, as Ellen Hart, Ellen Kerrison and Ellen Pollard. Sadly Ellen was to die just eight months later (p.18).

Shortly after, Catherine and Cornelius and their young family went to Tasmania, to Supply River, an area where Cornelius’s father, Stephen, was well-known and respected. There they prospered acquiring land at Winkleigh, Beaconsfield, and a small house in Launceston. Catherine gave birth to another eight children. Eight of their eleven children were to survive to adulthood. And in 1883, presumably after William Pollard’s death, the couple were able to legitimize their union by getting married in St John’s Church in Launceston. (p.25)

In 1892, Cornelius and Catherine began making monetary donations to the Sisters of Charity in County Mayo. That generosity was the foundation of a lifelong correspondence and friendship. It was reciprocated by the nuns when Catherine visited them in Ireland in 1899. On her trip Catherine visited quite a few places, Mayo, Galway, Cork and the Lakes of Killarney, Westminster Abbey, the Albert Hall and St Paul’s Cathedral and was delighted at seeing Queen Victoria at Windsor. She also reestablished connections with family members in Galway including her cousin, Mark Hart. Some lady, she was, much admired by all who met her, including Sister Greham, one of the the Ballaghderin nuns, who wrote they were all inspired by her story and they would do as much as they could for the orphans in their care. (pp.36-7)

Rex and Anthea still have family heirlooms celebrating their association with their Irish Famine orphan. If i remember correctly, when they appeared in Barrie and Síobhán’s Mná Díbeartha, they were holding a green felt bag where Catherine stored her letters, and a cloth bookmark inscribed with ‘Erin go Bragh’.

That’s quite a selection to be going on with. They are rich in their diversity, are they not?

I’d planned to finish by saying something about the value of going beyond the lifetime of a particular orphan, maybe even remind you of some of the issues I’d raised in previous posts–how to evaluate sources, urge you to write Aboriginal people in to your family history, set your orphan in a local historical context, always acknowledge your sources–that kind of thing. But enough.

Just one more drum beat, from Connell Foley again, “In the End”, Atlas of the Great Irish Famine, p.678

“…when we talk about political will being required to change this embedded inequity we talk about a tiny percentage of political will when what is needed is a large dose of committed leadership across the world and the ability to work to a common cause which has only been hinted at in the state-centred constituency feeding politics that dominates us and we each as individuals feels helpless to shape or change so in the end we come to the conclusion that this is really what is required to deliver the full realisation of human rights as they were written and agreed not just some civil and political freedoms half way up maslow’s hierarchy but those most basic needs required by every individual to at least live a life of dignity…”

and what do you think they are?

Trevor, thank you for the terrific work that you are now doing via your blog. I personally appreciate you publishing the stories and updates of these wonderful young women who contributed so much to our fledgling nation from the time that they arrived some 170+ years ago. In particular, thank you for publishing our family’s story of young Julia Loftus, much appreciated. Keep up the good work – their legacy lives on…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have included your blog in INTERESTING BLOGS in FRIDAY FOSSICKING at

https://thatmomentintime-crissouli.blogspot.com/2018/03/friday-fossicking-23d-march-2018.html

Thank you, Chris

Thank you for the mention and permission to include your photo in Irish Graves… and I’d chosen your post prior to that. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Trevor, This is fascinating. Please keep up the good work, Bryan

LikeLike

Thanks Bryan. Hope Dom’s shoulder is improving and You are feeling at home in Cork.

LikeLike

Terrific – thank you. Following up wife’s 15 year old ancestor Catherine Brien who arrived July 1849 on Lady Peel with sister Bridget. Background from these stories great.

Keep up the good work.

LikeLike